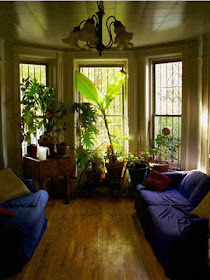

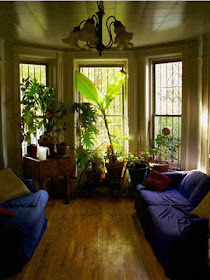

My flatmate Trevor is finally moving in this weekend! (This sunny room - the brightest in the apartment - will be his bedroom, so one or both of these sofas - inherited from Paul and Alice, who found them on the street - will return to the street.) Three months on my own in this apartment have made me both more eager at his arrival and more anxious about it. But the anxiety is general (sharing what's come to feel like my space with someone else) while the eagerness is particular (what fun to share with him), so while the transition will surely have its tensions a happy ending is assured

My flatmate Trevor is finally moving in this weekend! (This sunny room - the brightest in the apartment - will be his bedroom, so one or both of these sofas - inherited from Paul and Alice, who found them on the street - will return to the street.) Three months on my own in this apartment have made me both more eager at his arrival and more anxious about it. But the anxiety is general (sharing what's come to feel like my space with someone else) while the eagerness is particular (what fun to share with him), so while the transition will surely have its tensions a happy ending is assuredFriday, November 30, 2007

Welcome

My flatmate Trevor is finally moving in this weekend! (This sunny room - the brightest in the apartment - will be his bedroom, so one or both of these sofas - inherited from Paul and Alice, who found them on the street - will return to the street.) Three months on my own in this apartment have made me both more eager at his arrival and more anxious about it. But the anxiety is general (sharing what's come to feel like my space with someone else) while the eagerness is particular (what fun to share with him), so while the transition will surely have its tensions a happy ending is assured

My flatmate Trevor is finally moving in this weekend! (This sunny room - the brightest in the apartment - will be his bedroom, so one or both of these sofas - inherited from Paul and Alice, who found them on the street - will return to the street.) Three months on my own in this apartment have made me both more eager at his arrival and more anxious about it. But the anxiety is general (sharing what's come to feel like my space with someone else) while the eagerness is particular (what fun to share with him), so while the transition will surely have its tensions a happy ending is assuredThursday, November 29, 2007

A joke?

Just got back from a packed room where Ben Lee, the university provost, presented the latest version of the "university-wide academic plan" part of the university's "strategic plan." We've all been hearing rumors about impending "consolidation" of the university's many divisions and myriad programs, so people from all over the university showed up, eager to hear if their divisions or programs would survive into the new plan, whatever it would be, and if so in what form. This presentation was originally scheduled for early October, so the suspense has has a long time to build. (The plan turns out to be vague and politic enough that new  things will happen along side old things rather than displacing or reorganizing them, at least right away. Lang's dilution continues.)

things will happen along side old things rather than displacing or reorganizing them, at least right away. Lang's dilution continues.)

It's hard to know how serious any of this is - the provost kept stressing that it was provisional, temporary - or how things will be decided. Provost Lee is rather a hard man to read. When he first came in and found people standing in the back and along the sides and sitting in the aisles, he remarked that he was tempted to call out "fire drill!" Although delivered flatly, this was potentially very funny, but it is an odd thing to say to a bunch of people who are wondering if the perennially New School is a place to try to stay or start planning to leave. So: was it a joke? Or was it a slip - consciously no more than a way of noting that the room was overfull but unconsciously registering awareness of the anxieties of the people assembled? Should we have laughed so generously?

things will happen along side old things rather than displacing or reorganizing them, at least right away. Lang's dilution continues.)

things will happen along side old things rather than displacing or reorganizing them, at least right away. Lang's dilution continues.)It's hard to know how serious any of this is - the provost kept stressing that it was provisional, temporary - or how things will be decided. Provost Lee is rather a hard man to read. When he first came in and found people standing in the back and along the sides and sitting in the aisles, he remarked that he was tempted to call out "fire drill!" Although delivered flatly, this was potentially very funny, but it is an odd thing to say to a bunch of people who are wondering if the perennially New School is a place to try to stay or start planning to leave. So: was it a joke? Or was it a slip - consciously no more than a way of noting that the room was overfull but unconsciously registering awareness of the anxieties of the people assembled? Should we have laughed so generously?

Wednesday, November 28, 2007

Stolen gold

Argh, beaten at my own game! I wish I'd taken this picture (love that last burst of green!), but it's the work of the mysterious "jesse" who responded to my last post. I think I know who this "jesse" is - but the person I'm thinking of lives in Brooklyn, while the slide show from which I pinched this picture is called Autumn in Manhattan (though some of its pictures seem to be winter!). A sly slide? Should I fall for this or not? Sounds like a plot twist which snuck across the wall into his room from next door, where I'm told Paul Auster writes...

Argh, beaten at my own game! I wish I'd taken this picture (love that last burst of green!), but it's the work of the mysterious "jesse" who responded to my last post. I think I know who this "jesse" is - but the person I'm thinking of lives in Brooklyn, while the slide show from which I pinched this picture is called Autumn in Manhattan (though some of its pictures seem to be winter!). A sly slide? Should I fall for this or not? Sounds like a plot twist which snuck across the wall into his room from next door, where I'm told Paul Auster writes...

Monday, November 26, 2007

Saturday, November 24, 2007

Christmas coming

The minute Thanksgiving is over it's prime Christmas shopping season. (In some stores the Christmas music started right after Hallowe'en!) I'll settle for these flowers, preparing in their own way.

The minute Thanksgiving is over it's prime Christmas shopping season. (In some stores the Christmas music started right after Hallowe'en!) I'll settle for these flowers, preparing in their own way.

Friday, November 23, 2007

Food for thought

Here are some of the books I picked up at AAR. Lest you conclude I've thrown in my lot with new and postmodern Christianities to the exclusion of other traditions and approaches let me assure you these are just the ones publishers had in stock and at substantial discounts. (Thy Kingdom Come was free as an examination copy, a relief since it turns out to be junk.) I ordered a good number of other books, including Graham Harvey's Animism: Respecting the Living World, Ken Jones' The New Social Face of Buddhism, David Kyuman Kim's Melancholic Freedom: Agency and the Spirit of Democracy and David Loy's The Great Awakening: A Buddhist Social Theory. I would have picked up Charles Taylor's The Secular Age but for its girth and ordered Gregory Alles' Religious Studies: A Global View but for the pricetag ($180!).

Here are some of the books I picked up at AAR. Lest you conclude I've thrown in my lot with new and postmodern Christianities to the exclusion of other traditions and approaches let me assure you these are just the ones publishers had in stock and at substantial discounts. (Thy Kingdom Come was free as an examination copy, a relief since it turns out to be junk.) I ordered a good number of other books, including Graham Harvey's Animism: Respecting the Living World, Ken Jones' The New Social Face of Buddhism, David Kyuman Kim's Melancholic Freedom: Agency and the Spirit of Democracy and David Loy's The Great Awakening: A Buddhist Social Theory. I would have picked up Charles Taylor's The Secular Age but for its girth and ordered Gregory Alles' Religious Studies: A Global View but for the pricetag ($180!).

Thursday, November 22, 2007

The long term

Now here's a question for you. At a dinner last night with my parents and some of their friends, a medical doctor - the "black sheep" of a Plymouth Brethren family who told me he is "on the Dawkins side" - asked me: where did I see religion 500 years from now?

A good question, and not one I've encountered before. My answer was that I didn't think one side or the other (of believers and unbelievers) would win out decisively, that it would likely swing back and forth. Why think the next 500 years will be like the last 200 rather than the last 5000?

I'm no futurologist, and I'll admit that when I think about the future I think in terms of 5 and 50 years - and 50,000,000 - but not 500. (Was it Albert Camus who said that the absurd was the world 50 years after your death when nobody remembers you or anyone you cared about?) But the question isn't really about the future anyway, so much as about unchanging things in human nature and culture - and whatever else is at work in the world around us. In the aftermath of secularization theory, I don't think that religion is disappearing - what people with my kind of education were all taught to expect until very recently. Indeed I feel sometimes like we're coming out of a period of the eclipse of religion. But there are different ways of understanding the resilience of religion. I'm sort of a Marxist about religion: as long as there is injustice in human affairs there will be religion. But is that all? In class when we were reading Marx and I was, once again, surprising myself with the fervor of my enthusiasm for Marx's hopes, I told students that one could be a Marxist on all this and still be religious - until there is a revolution leading to true human history, religion will be human protest at human oppression, but once the oppression is gone we will be free to form a religion true to what's out there, unconstrained by the needs for consolation and justification. So: struggle for justice now, and leave religion for the future. Let religion (not just your own tradition necessarily) strengthen you in this noble struggle but never let it overshadow or distract from it.

Others wouldn't wait until the revolution for eschatological verification (a term of John Hick's which I'm misusing but not travestying). God (or the Tao or Purpose or whatever) is here and always has been and always will be, so of course there'll be religion in 500 years. It'll be available then (assuming there are still human beings kicking around in something like our form) just as it is now.

I wonder if my interlocutor hopes or expects that 500 years from now religion will be a distant and uninteresting memory, indeed an incomprehensible one. The people of the future will live our their lifespan doing rewarding things and then let go, satisfied in knowing they had the privilege of being part of the extraordinary world of meaning and relationship which human beings have been able to create around themselves. Indeed, that is already available now.

Maybe part of the privilege of living right now is that both of these are available, and available to stimulate and challenge each other - and my answer was not so much an unwillingness to think beyond the present as a hope that the present's possibilities persist. Maybe...

A good question, and not one I've encountered before. My answer was that I didn't think one side or the other (of believers and unbelievers) would win out decisively, that it would likely swing back and forth. Why think the next 500 years will be like the last 200 rather than the last 5000?

I'm no futurologist, and I'll admit that when I think about the future I think in terms of 5 and 50 years - and 50,000,000 - but not 500. (Was it Albert Camus who said that the absurd was the world 50 years after your death when nobody remembers you or anyone you cared about?) But the question isn't really about the future anyway, so much as about unchanging things in human nature and culture - and whatever else is at work in the world around us. In the aftermath of secularization theory, I don't think that religion is disappearing - what people with my kind of education were all taught to expect until very recently. Indeed I feel sometimes like we're coming out of a period of the eclipse of religion. But there are different ways of understanding the resilience of religion. I'm sort of a Marxist about religion: as long as there is injustice in human affairs there will be religion. But is that all? In class when we were reading Marx and I was, once again, surprising myself with the fervor of my enthusiasm for Marx's hopes, I told students that one could be a Marxist on all this and still be religious - until there is a revolution leading to true human history, religion will be human protest at human oppression, but once the oppression is gone we will be free to form a religion true to what's out there, unconstrained by the needs for consolation and justification. So: struggle for justice now, and leave religion for the future. Let religion (not just your own tradition necessarily) strengthen you in this noble struggle but never let it overshadow or distract from it.

Others wouldn't wait until the revolution for eschatological verification (a term of John Hick's which I'm misusing but not travestying). God (or the Tao or Purpose or whatever) is here and always has been and always will be, so of course there'll be religion in 500 years. It'll be available then (assuming there are still human beings kicking around in something like our form) just as it is now.

I wonder if my interlocutor hopes or expects that 500 years from now religion will be a distant and uninteresting memory, indeed an incomprehensible one. The people of the future will live our their lifespan doing rewarding things and then let go, satisfied in knowing they had the privilege of being part of the extraordinary world of meaning and relationship which human beings have been able to create around themselves. Indeed, that is already available now.

Maybe part of the privilege of living right now is that both of these are available, and available to stimulate and challenge each other - and my answer was not so much an unwillingness to think beyond the present as a hope that the present's possibilities persist. Maybe...

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

What I believe (not yet invincibly)

Strange, as I reflect back on the AAR experience I find that, once again, I have shifted in my view of religion. I seem - egad! - to be moving toward a pro-religion stance. Not that religion is good for people, though that might be true (often it's not), but that it might in some sense be - yoicks! - true.

Time was, I took refuge in the formulation (coined by Joe Bulbulia) distinguishing religious studies from theology, "they study God, we study them." That made religious studies safely kin of anthropology, history and the other human sciences. Religion(s) might or might not be true - we learn to leave those questions open (or aside) - but our business is with human beings and their deepest convictions. Religious studies is a necessary discipline because the other disciplines do not take the depth of these convictions as seriously as it deserves - not as potentially true but as part of human experience and culture.

But now I find I'm closer to a different position: that religious studies is a necessary discipline because it alone confronts students (and we're all still students on this one) with the fact that there is no consensus on what is real. One studies religious traditions not only because they are expressions of the human spirit and "nothing human is foreign to me," but because they collectively point beyond the secular pieties of academic life. I'm sounding a bit like William James, who described the writing of his Varieties of Religious Experience thus:

But now I find I'm closer to a different position: that religious studies is a necessary discipline because it alone confronts students (and we're all still students on this one) with the fact that there is no consensus on what is real. One studies religious traditions not only because they are expressions of the human spirit and "nothing human is foreign to me," but because they collectively point beyond the secular pieties of academic life. I'm sounding a bit like William James, who described the writing of his Varieties of Religious Experience thus:

the problem I have set myself is a hard one: first, to defend (against all the prejudices of my "class") "experience" against "philosophy" as being the real backbone of the world's religious life ... and second, to make the hearer or reader believe, what I myself invincibly do believe, that although all the special manifestations of religion may have been absurd (I mean its creeds and theories), yet the life of it as a whole is mankind's most important function.

I don't know about "experience" (though James' rich conception of it is far better than common ones); I want to say something about the real. Not just that there are different views of what's real - is there life after death, do animals have souls, is there purpose in the universe, does the devil exist, etc. - or that there will always be different views here. No, part of me wants to say that religious traditions record and generate experiences of a world where more is possible than modernity imagines or allows. I'm not talking supernaturalism, necessarily, since I accept Dewey's (and before him Durkheim's) criticism of an unproblematic conception of the natural, but something more like Wislawa Szymborska's laconic observation in a poem I've quoted before (a potential epigraph for my good book):

I'm not saying I have experienced more than commonplace miracles, but that I am finding myself inclining toward the view that the commonplace miracles are just the start, and that the study of religion forces (or permits) us to consider where it might lead.

Here's James again, in another letter about the Varieties, and then I'll close for today:

Here's James again, in another letter about the Varieties, and then I'll close for today:

The Divine, for my active life, is limited to impersonal and abstract concepts which, as ideals, interest and determine me, but do so faintly in comparison with what a feeling of God might effect if I had one.... yet there is something in me which makes response when I hear utterances from the quarter made by others. I recognize the deeper voice. Something tells me: -- ‘thither lies truth’ ...

Time was, I took refuge in the formulation (coined by Joe Bulbulia) distinguishing religious studies from theology, "they study God, we study them." That made religious studies safely kin of anthropology, history and the other human sciences. Religion(s) might or might not be true - we learn to leave those questions open (or aside) - but our business is with human beings and their deepest convictions. Religious studies is a necessary discipline because the other disciplines do not take the depth of these convictions as seriously as it deserves - not as potentially true but as part of human experience and culture.

But now I find I'm closer to a different position: that religious studies is a necessary discipline because it alone confronts students (and we're all still students on this one) with the fact that there is no consensus on what is real. One studies religious traditions not only because they are expressions of the human spirit and "nothing human is foreign to me," but because they collectively point beyond the secular pieties of academic life. I'm sounding a bit like William James, who described the writing of his Varieties of Religious Experience thus:

But now I find I'm closer to a different position: that religious studies is a necessary discipline because it alone confronts students (and we're all still students on this one) with the fact that there is no consensus on what is real. One studies religious traditions not only because they are expressions of the human spirit and "nothing human is foreign to me," but because they collectively point beyond the secular pieties of academic life. I'm sounding a bit like William James, who described the writing of his Varieties of Religious Experience thus:the problem I have set myself is a hard one: first, to defend (against all the prejudices of my "class") "experience" against "philosophy" as being the real backbone of the world's religious life ... and second, to make the hearer or reader believe, what I myself invincibly do believe, that although all the special manifestations of religion may have been absurd (I mean its creeds and theories), yet the life of it as a whole is mankind's most important function.

William James, "[Experience and Religion: A Comment],"

extract from a letter to Frances R. Morse, in The Writings of William James,

ed. John McDermott (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), 740-1

extract from a letter to Frances R. Morse, in The Writings of William James,

ed. John McDermott (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), 740-1

I don't know about "experience" (though James' rich conception of it is far better than common ones); I want to say something about the real. Not just that there are different views of what's real - is there life after death, do animals have souls, is there purpose in the universe, does the devil exist, etc. - or that there will always be different views here. No, part of me wants to say that religious traditions record and generate experiences of a world where more is possible than modernity imagines or allows. I'm not talking supernaturalism, necessarily, since I accept Dewey's (and before him Durkheim's) criticism of an unproblematic conception of the natural, but something more like Wislawa Szymborska's laconic observation in a poem I've quoted before (a potential epigraph for my good book):

Commonplace miracle:

that so many commonplace miracles happen.

that so many commonplace miracles happen.

I'm not saying I have experienced more than commonplace miracles, but that I am finding myself inclining toward the view that the commonplace miracles are just the start, and that the study of religion forces (or permits) us to consider where it might lead.

Here's James again, in another letter about the Varieties, and then I'll close for today:

Here's James again, in another letter about the Varieties, and then I'll close for today:The Divine, for my active life, is limited to impersonal and abstract concepts which, as ideals, interest and determine me, but do so faintly in comparison with what a feeling of God might effect if I had one.... yet there is something in me which makes response when I hear utterances from the quarter made by others. I recognize the deeper voice. Something tells me: -- ‘thither lies truth’ ...

William James, letter to James Leuba,

cited in The Varieties of Religious Experience

(1902; repr. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1985), xxiv

cited in The Varieties of Religious Experience

(1902; repr. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1985), xxiv

(The pictures, incidentally, are from Torrey Pines Beach this afternoon. The first our most recent rockslide, the second the promontory leading to Flat Rock.)

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

Art lives

Here are some of the amazing images from an article in the latest issue of Scientific American (I should really get myself a subscription, not just reading it when I'm at my parents') on light microscopy, which seems to involve the use of dyes to help distinguish different features and functions of biological research. In any case, what a gallery they make!

Here are some of the amazing images from an article in the latest issue of Scientific American (I should really get myself a subscription, not just reading it when I'm at my parents') on light microscopy, which seems to involve the use of dyes to help distinguish different features and functions of biological research. In any case, what a gallery they make!

Enough (AAR 3)

A third day of AAR and I'm sated! Today wasn't the best day in terms of scheduled activities: a philosophy of religion panel where three luminaries praised a new book by a junior scholar who, when it came his turn to speak, did a Sally Field, becoming a babbling deer-in-the-headlights so embarrassing we had to leave. And a tour of Religious and Sacred Sites of San Diego was hurried and arbitary. The pics are from the three sites of the tour: models of the California missions in the museum at Mission San Diego de Alcala; the view up in the entirely mosaic-covered Serbian Orthodox

A third day of AAR and I'm sated! Today wasn't the best day in terms of scheduled activities: a philosophy of religion panel where three luminaries praised a new book by a junior scholar who, when it came his turn to speak, did a Sally Field, becoming a babbling deer-in-the-headlights so embarrassing we had to leave. And a tour of Religious and Sacred Sites of San Diego was hurried and arbitary. The pics are from the three sites of the tour: models of the California missions in the museum at Mission San Diego de Alcala; the view up in the entirely mosaic-covered Serbian Orthodox  church of St George (built in 1967, the Italian mosaic artists not always faithful in their working out of designs sent from Serbia), and one of the few surviving buildings from a Theosophical compound on Point Loma.

church of St George (built in 1967, the Italian mosaic artists not always faithful in their working out of designs sent from Serbia), and one of the few surviving buildings from a Theosophical compound on Point Loma.But the day was saved by impromptu chats with my old grad school classmate Bill and my old adviser Jeff. And then I took two Buddhologist friends I met through the Academic Study and Teaching of Religion section to dinner on the beach in Del Mar. After dinner we walked along the nocturnal beach, eventually standing watching and

listening, and I noticed the ocean has a full orchestra of sounds, from rumbling to rainlike, assorted hisses and shushes, tinkling or tinselly sounds, the sound of crumpled paper, the occasional pop and the saturated silence Japanese manga sound out as a (presumably unaspirated) シーーン shiiiiiiin. I'm sure I've written this here before, or should have, the only poem I know by heart:

listening, and I noticed the ocean has a full orchestra of sounds, from rumbling to rainlike, assorted hisses and shushes, tinkling or tinselly sounds, the sound of crumpled paper, the occasional pop and the saturated silence Japanese manga sound out as a (presumably unaspirated) シーーン shiiiiiiin. I'm sure I've written this here before, or should have, the only poem I know by heart:The heart can think of no devotion

Greater than being shore to the ocean--

Holding the curve of one position,

Counting an endless repetition.

Greater than being shore to the ocean--

Holding the curve of one position,

Counting an endless repetition.

Who really needs religion or its study when there's friends and Robert Frost and the vast precision of the ocean? (But I'll take the lot!)

Monday, November 19, 2007

AAR 2

Another fun-filled day at AAR:

• a fascinating morning session on the study of "lived religion" in North America with papers on Mexican-American murals in Los Angeles (below: part of the facade of St. Lucy's church, painted by George Yepes; the Virgen de Guadalupe is holding, pieta-style, a dead gang member), homosocial fundamentalists, religious and political concerns of pro-life activists, and accounting for the persistent appeal of American "prosperity theology" televangelism among the poor in Jamaica ("Lived religion" is a void in which I find myself as a thought- text- philosophy person dissolving without a trace, but I kind of enjoy it.)

among the poor in Jamaica ("Lived religion" is a void in which I find myself as a thought- text- philosophy person dissolving without a trace, but I kind of enjoy it.)

• an hour browsing the book displays (possibly my last chance to scope out the offerings of theological and pastoral presses, what with the AAR/SBL split; I found some interesting stuff for the coming Spring's course on the religious right and picked up a souvenir pen from an unmanned Regent University desk)

• coffee with dear old friend Roberto

• an experimental session on the reading of Buddhist texts in which we read Buddhagosa (5th century Sri Lanka, Theravada) through Shinran (12th century Japan, at left, Pure Land [Shin]) in small groups - too little time but wonderfully exciting - the time just flew. (I'd forgotten how I enjoy Buddhist literature.)

(I'd forgotten how I enjoy Buddhist literature.)

• a happy reunion with a Buddhist environmentalist friend I met first an AAR a few years ago

• a snoozy panel on continental philosophy's recovery of religion (perhaps I was snoozy, not the panel, but it seemed oh so dry and abstract compared to lived religion and Buddhist texts)

• a dull talk by this year's Templeton Prize winner, the distinguished Canadian social theorist and philosopher Charles Taylor (I was a great fan of Taylor's work as an undergraduate, while he was briefly at Oxford, but have drifted away ... and he's drifted, too, to the point where he's happy to accept a prize connected to the promotion of research in "spiritual realities"!)

• the Princeton reception, which was huge and full of people I barely recognized - including my old pal Galen, over from Japan (Galen was one of my first friends in graduate school and we've had a running discussion about why Japanese Shin Buddhist ideas don't appeal to Americans for almost two decades now, long enough for postmodernism - such affinities to Shin, Galen insisted! - to rise and subside again...)

Too much for one day, really, but I relished every moment (well, except continental philosophy and Taylor...). How strange to think that, for all my living in the navel of the universe, I am as starved for colleagues and conversations in religious studies as folks who teach in two-person departments in remote colleges in the middle of nowhere!

• a fascinating morning session on the study of "lived religion" in North America with papers on Mexican-American murals in Los Angeles (below: part of the facade of St. Lucy's church, painted by George Yepes; the Virgen de Guadalupe is holding, pieta-style, a dead gang member), homosocial fundamentalists, religious and political concerns of pro-life activists, and accounting for the persistent appeal of American "prosperity theology" televangelism

among the poor in Jamaica ("Lived religion" is a void in which I find myself as a thought- text- philosophy person dissolving without a trace, but I kind of enjoy it.)

among the poor in Jamaica ("Lived religion" is a void in which I find myself as a thought- text- philosophy person dissolving without a trace, but I kind of enjoy it.)• an hour browsing the book displays (possibly my last chance to scope out the offerings of theological and pastoral presses, what with the AAR/SBL split; I found some interesting stuff for the coming Spring's course on the religious right and picked up a souvenir pen from an unmanned Regent University desk)

• coffee with dear old friend Roberto

• an experimental session on the reading of Buddhist texts in which we read Buddhagosa (5th century Sri Lanka, Theravada) through Shinran (12th century Japan, at left, Pure Land [Shin]) in small groups - too little time but wonderfully exciting - the time just flew.

(I'd forgotten how I enjoy Buddhist literature.)

(I'd forgotten how I enjoy Buddhist literature.)• a happy reunion with a Buddhist environmentalist friend I met first an AAR a few years ago

• a snoozy panel on continental philosophy's recovery of religion (perhaps I was snoozy, not the panel, but it seemed oh so dry and abstract compared to lived religion and Buddhist texts)

• a dull talk by this year's Templeton Prize winner, the distinguished Canadian social theorist and philosopher Charles Taylor (I was a great fan of Taylor's work as an undergraduate, while he was briefly at Oxford, but have drifted away ... and he's drifted, too, to the point where he's happy to accept a prize connected to the promotion of research in "spiritual realities"!)

• the Princeton reception, which was huge and full of people I barely recognized - including my old pal Galen, over from Japan (Galen was one of my first friends in graduate school and we've had a running discussion about why Japanese Shin Buddhist ideas don't appeal to Americans for almost two decades now, long enough for postmodernism - such affinities to Shin, Galen insisted! - to rise and subside again...)

Too much for one day, really, but I relished every moment (well, except continental philosophy and Taylor...). How strange to think that, for all my living in the navel of the universe, I am as starved for colleagues and conversations in religious studies as folks who teach in two-person departments in remote colleges in the middle of nowhere!

Sunday, November 18, 2007

AAR 1

I love AAR. It's my only chance to be surrounded by other religious studies people all year, and since I've given myself permission to use it as an occasion to explore new fields rather than burrow deeper into a single subfield, I learn all sorts of stuff. More than that, it offers some of the fun of slumming at someone else's professional society, a quite diverting anthropological experience - and a way to maintain a sense of irony about the academic game! A certain distance is probably healthy as otherwise one would be overwhelmed by all one does not know or even know how to know about (or find interesting, for that matter!). Today, for instance, I attended a panel on religion  in video games and a discussion led by Tavis Smiley on his book The contract with black America, had lunch with my friend Beth, learned lots about the difficult separation AAR has initiated from SBL (the Society for Biblical Literature), had dinner with a Romanian grad student who told me about reading through Mircea Eliade's unpublished papers in Chicago, and finally heard the presidential address by my old adviser and colleague Jeff Stout on "The Folly of Secularism."

in video games and a discussion led by Tavis Smiley on his book The contract with black America, had lunch with my friend Beth, learned lots about the difficult separation AAR has initiated from SBL (the Society for Biblical Literature), had dinner with a Romanian grad student who told me about reading through Mircea Eliade's unpublished papers in Chicago, and finally heard the presidential address by my old adviser and colleague Jeff Stout on "The Folly of Secularism."

Two of the panels merit a brief description. The first one, called "Born digital and born again digital," looked first at religion in and through video/computer games, and then at some evangelical Christian games. The former included an introduction to Kabbalah which took you through a serious of futile games on the way to teaching you to understand "the game of life" and that only Kabbalah will save you from losing at it, and a new age program called The Journey to Wild Divine which you manipulate through a special device with sensors on the three middle fingers of your left hand: it reads your temperature and notes your pulse, and feeds them into game-like situations. The latter took us from the earliest evangelical games in the early 1990s, where conventional shooting programs were leased and modified (Wolfenstein, where a US agent hunts down Nazis in a labyrinthine German castle, becomes Super 3-D Noah's Ark, where Noah sling-shots food at animals in the labyrinthine corridors of his ark!), to the recent video game based on the Left Behind books, where members of the "Tribulation Force" witness to, pray for or shoot assorted characters in the streets of southern Manhattan eighteen months after the Rapture. This was the first panel on this topic, and drew a lot of gamers. It has a ways to go before it's truly religious studies, though. The participants all accepted the virtual/real distinction (or question: isn't the virtual real too?) which frames secular discussions on games, but weren't prepared to concede that the nature of reality isn't a given, and that different religious traditions describe different realities: for some, the real is less real than the virtual.

it reads your temperature and notes your pulse, and feeds them into game-like situations. The latter took us from the earliest evangelical games in the early 1990s, where conventional shooting programs were leased and modified (Wolfenstein, where a US agent hunts down Nazis in a labyrinthine German castle, becomes Super 3-D Noah's Ark, where Noah sling-shots food at animals in the labyrinthine corridors of his ark!), to the recent video game based on the Left Behind books, where members of the "Tribulation Force" witness to, pray for or shoot assorted characters in the streets of southern Manhattan eighteen months after the Rapture. This was the first panel on this topic, and drew a lot of gamers. It has a ways to go before it's truly religious studies, though. The participants all accepted the virtual/real distinction (or question: isn't the virtual real too?) which frames secular discussions on games, but weren't prepared to concede that the nature of reality isn't a given, and that different religious traditions describe different realities: for some, the real is less real than the virtual.

The second panel, with an unwieldy title, considered intellectual, historical and ideological ramifications of the split between AAR and SBL. This requires a little context: SBL used to be quite big, and AAR (originally NABI, the National Association of Bible Instructors) very small, and they had conferences together to get to critical mass. (The conferences are held in parallel; the associations remain distinct, with distinct leadership, programming and membership.) In recent years, both have grown, but AAR is now bigger, and a few years ago its leadership somewhat precipitously announced that AAR-SBL had become too big: from now on, AAR would have meetings on its own. The decision bothered lots of people because of the autocratic way it was made, but also because the argument about size seemed to be concealing deeper reservations about SBL. Today's panel was an AAR panel but most of the people present work in Biblical studies (many have long been members of both AAR and SBL) and I got to hear the aggrieved and grieving SBL side of what I had until taken to be a good if badly handled decision for AAR. I continue to think AAR is better off on its own - there's no reason to privilege one particular subfield, especially the culturally and historically dominant one - but learned that my preconceptions about SBL were largely mistaken. In some respects SBL is more scholarly than AAR, covering a broader array of thematic approaches and gathering a more international field of scholars. Elizabeth Clark gave an interesting history of the way Biblical and religious studies made their way into the curricula of different kinds of US educational institutions in the 19th century (Biblical studies came to colleges and universities as part of "humanities," an effort, she claimed, to anchor moral education in a conception of religion broader than Christianity). But most interesting to me was the observation by Gregory D. Alles that religious studies outside the west has a different focus from the AAR and one in its way closer to that of SBL: instead of studying the religions of others, it tends to focus on local traditions. Paradoxically, AAR's attempt to deprovincialize its image by parting from SBL provincializes it anew!

Today's panel was an AAR panel but most of the people present work in Biblical studies (many have long been members of both AAR and SBL) and I got to hear the aggrieved and grieving SBL side of what I had until taken to be a good if badly handled decision for AAR. I continue to think AAR is better off on its own - there's no reason to privilege one particular subfield, especially the culturally and historically dominant one - but learned that my preconceptions about SBL were largely mistaken. In some respects SBL is more scholarly than AAR, covering a broader array of thematic approaches and gathering a more international field of scholars. Elizabeth Clark gave an interesting history of the way Biblical and religious studies made their way into the curricula of different kinds of US educational institutions in the 19th century (Biblical studies came to colleges and universities as part of "humanities," an effort, she claimed, to anchor moral education in a conception of religion broader than Christianity). But most interesting to me was the observation by Gregory D. Alles that religious studies outside the west has a different focus from the AAR and one in its way closer to that of SBL: instead of studying the religions of others, it tends to focus on local traditions. Paradoxically, AAR's attempt to deprovincialize its image by parting from SBL provincializes it anew!

in video games and a discussion led by Tavis Smiley on his book The contract with black America, had lunch with my friend Beth, learned lots about the difficult separation AAR has initiated from SBL (the Society for Biblical Literature), had dinner with a Romanian grad student who told me about reading through Mircea Eliade's unpublished papers in Chicago, and finally heard the presidential address by my old adviser and colleague Jeff Stout on "The Folly of Secularism."

in video games and a discussion led by Tavis Smiley on his book The contract with black America, had lunch with my friend Beth, learned lots about the difficult separation AAR has initiated from SBL (the Society for Biblical Literature), had dinner with a Romanian grad student who told me about reading through Mircea Eliade's unpublished papers in Chicago, and finally heard the presidential address by my old adviser and colleague Jeff Stout on "The Folly of Secularism."Two of the panels merit a brief description. The first one, called "Born digital and born again digital," looked first at religion in and through video/computer games, and then at some evangelical Christian games. The former included an introduction to Kabbalah which took you through a serious of futile games on the way to teaching you to understand "the game of life" and that only Kabbalah will save you from losing at it, and a new age program called The Journey to Wild Divine which you manipulate through a special device with sensors on the three middle fingers of your left hand:

it reads your temperature and notes your pulse, and feeds them into game-like situations. The latter took us from the earliest evangelical games in the early 1990s, where conventional shooting programs were leased and modified (Wolfenstein, where a US agent hunts down Nazis in a labyrinthine German castle, becomes Super 3-D Noah's Ark, where Noah sling-shots food at animals in the labyrinthine corridors of his ark!), to the recent video game based on the Left Behind books, where members of the "Tribulation Force" witness to, pray for or shoot assorted characters in the streets of southern Manhattan eighteen months after the Rapture. This was the first panel on this topic, and drew a lot of gamers. It has a ways to go before it's truly religious studies, though. The participants all accepted the virtual/real distinction (or question: isn't the virtual real too?) which frames secular discussions on games, but weren't prepared to concede that the nature of reality isn't a given, and that different religious traditions describe different realities: for some, the real is less real than the virtual.

it reads your temperature and notes your pulse, and feeds them into game-like situations. The latter took us from the earliest evangelical games in the early 1990s, where conventional shooting programs were leased and modified (Wolfenstein, where a US agent hunts down Nazis in a labyrinthine German castle, becomes Super 3-D Noah's Ark, where Noah sling-shots food at animals in the labyrinthine corridors of his ark!), to the recent video game based on the Left Behind books, where members of the "Tribulation Force" witness to, pray for or shoot assorted characters in the streets of southern Manhattan eighteen months after the Rapture. This was the first panel on this topic, and drew a lot of gamers. It has a ways to go before it's truly religious studies, though. The participants all accepted the virtual/real distinction (or question: isn't the virtual real too?) which frames secular discussions on games, but weren't prepared to concede that the nature of reality isn't a given, and that different religious traditions describe different realities: for some, the real is less real than the virtual.The second panel, with an unwieldy title, considered intellectual, historical and ideological ramifications of the split between AAR and SBL. This requires a little context: SBL used to be quite big, and AAR (originally NABI, the National Association of Bible Instructors) very small, and they had conferences together to get to critical mass. (The conferences are held in parallel; the associations remain distinct, with distinct leadership, programming and membership.) In recent years, both have grown, but AAR is now bigger, and a few years ago its leadership somewhat precipitously announced that AAR-SBL had become too big: from now on, AAR would have meetings on its own. The decision bothered lots of people because of the autocratic way it was made, but also because the argument about size seemed to be concealing deeper reservations about SBL.

Today's panel was an AAR panel but most of the people present work in Biblical studies (many have long been members of both AAR and SBL) and I got to hear the aggrieved and grieving SBL side of what I had until taken to be a good if badly handled decision for AAR. I continue to think AAR is better off on its own - there's no reason to privilege one particular subfield, especially the culturally and historically dominant one - but learned that my preconceptions about SBL were largely mistaken. In some respects SBL is more scholarly than AAR, covering a broader array of thematic approaches and gathering a more international field of scholars. Elizabeth Clark gave an interesting history of the way Biblical and religious studies made their way into the curricula of different kinds of US educational institutions in the 19th century (Biblical studies came to colleges and universities as part of "humanities," an effort, she claimed, to anchor moral education in a conception of religion broader than Christianity). But most interesting to me was the observation by Gregory D. Alles that religious studies outside the west has a different focus from the AAR and one in its way closer to that of SBL: instead of studying the religions of others, it tends to focus on local traditions. Paradoxically, AAR's attempt to deprovincialize its image by parting from SBL provincializes it anew!

Today's panel was an AAR panel but most of the people present work in Biblical studies (many have long been members of both AAR and SBL) and I got to hear the aggrieved and grieving SBL side of what I had until taken to be a good if badly handled decision for AAR. I continue to think AAR is better off on its own - there's no reason to privilege one particular subfield, especially the culturally and historically dominant one - but learned that my preconceptions about SBL were largely mistaken. In some respects SBL is more scholarly than AAR, covering a broader array of thematic approaches and gathering a more international field of scholars. Elizabeth Clark gave an interesting history of the way Biblical and religious studies made their way into the curricula of different kinds of US educational institutions in the 19th century (Biblical studies came to colleges and universities as part of "humanities," an effort, she claimed, to anchor moral education in a conception of religion broader than Christianity). But most interesting to me was the observation by Gregory D. Alles that religious studies outside the west has a different focus from the AAR and one in its way closer to that of SBL: instead of studying the religions of others, it tends to focus on local traditions. Paradoxically, AAR's attempt to deprovincialize its image by parting from SBL provincializes it anew!

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Still standing

It was very strange to fly into San Diego at night just weeks after those fires. We had clear skies the whole way from JFK until just before San Diego, and it was hard not to see the clouds of the marine layer as clouds of smoke, and the areas of inky black between areas of grids of light as the burnt-out places where the brush fires raged...

Even stranger to come home past Crest Canyon - my old childhood friend, where I found and explored Middle Earth - but at night just deepest black, the void. Had the Santa Ana winds blown the fires all the way to the sea that first day of the infernos, that canyon would have gone up like a tinderbox. Waves of flame would have come rolling over its edge and down the hill all the way to the edge of the Pacific, burning all in its path - Del Mar was ordered to evacuate because it couldn't have been stopped - including our house.

Our house, my parents' house, the house where I grew up - still standing of course, spared by the change in winds - feels like a gift, a miracle. From three thousand miles away, I had in some vague way tried on for size the possibility that I might never see it again, never sit in those so familiar chairs on that beloved deck, where so much has happened, so many happy meals with close and visiting family and friends, going back to my sister's and my birthday parties as children. All the things on the walls, every book on a shelf, every dish in the kitchen. I can't claim anything like St. Francis' vision of Assisi suspended upside down from the sky but a smidgen of an inkling of that sense that everything that seems solid is not, that its persistence is in some profound sense gratuitous.

I'm writing this down before heading off to the AAR because I don't know how long this sense of gratuity will last. I don't know if one can or should hold on to it.

Even stranger to come home past Crest Canyon - my old childhood friend, where I found and explored Middle Earth - but at night just deepest black, the void. Had the Santa Ana winds blown the fires all the way to the sea that first day of the infernos, that canyon would have gone up like a tinderbox. Waves of flame would have come rolling over its edge and down the hill all the way to the edge of the Pacific, burning all in its path - Del Mar was ordered to evacuate because it couldn't have been stopped - including our house.

Our house, my parents' house, the house where I grew up - still standing of course, spared by the change in winds - feels like a gift, a miracle. From three thousand miles away, I had in some vague way tried on for size the possibility that I might never see it again, never sit in those so familiar chairs on that beloved deck, where so much has happened, so many happy meals with close and visiting family and friends, going back to my sister's and my birthday parties as children. All the things on the walls, every book on a shelf, every dish in the kitchen. I can't claim anything like St. Francis' vision of Assisi suspended upside down from the sky but a smidgen of an inkling of that sense that everything that seems solid is not, that its persistence is in some profound sense gratuitous.

I'm writing this down before heading off to the AAR because I don't know how long this sense of gratuity will last. I don't know if one can or should hold on to it.

Friday, November 16, 2007

Falling leaves

Here's the view from my office window! The leaves just started turning reddish yesterday, and by the time I get back from San Diego (I'm going for the American Academy of Religion meeting this weekend, and staying through Thanksgiving) I expect they'll all be gone. Late-starting falls go fast, I guess: the lovely yellow lozenge-shaped leaves on the big tree in the courtyard just to the left of these trees lost all its leaves between yesterday and today...

Here's the view from my office window! The leaves just started turning reddish yesterday, and by the time I get back from San Diego (I'm going for the American Academy of Religion meeting this weekend, and staying through Thanksgiving) I expect they'll all be gone. Late-starting falls go fast, I guess: the lovely yellow lozenge-shaped leaves on the big tree in the courtyard just to the left of these trees lost all its leaves between yesterday and today...Thursday, November 15, 2007

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

Underground Bible

I think I've mentioned that I quite enjoy the commuting life - 20 minutes in the subway on the way to and from school to read papers or the paper or a book, a nice buffer. I didn't mention that lots of other people read, too - and that the subway bestseller is the Bible. (Q'urans and Jewish scriptures are read, too.) Interesting to think about what it would be like for the Bible to be your traveling companion, its rod and its staff comforting you as you  traversed the false and forced intimacy with strangers of public New York City.

traversed the false and forced intimacy with strangers of public New York City.

More than just linking your places of work and of rest, subway Bible-reading lets you remember the overarching religious frame into which they, too, must fit. I'm reminded of the car of a grad school colleague's wife which filled with gospel music as soon as you turned the ignition: praise and worship in motion! Urban geographers sometimes talk about places like subways as "non-spaces," spaces disconnected from anyone's life or world, but here the valley of the underground is more than exalted. The hours which the career-builder rejected may be the cornerstones of a godly life.

traversed the false and forced intimacy with strangers of public New York City.

traversed the false and forced intimacy with strangers of public New York City.More than just linking your places of work and of rest, subway Bible-reading lets you remember the overarching religious frame into which they, too, must fit. I'm reminded of the car of a grad school colleague's wife which filled with gospel music as soon as you turned the ignition: praise and worship in motion! Urban geographers sometimes talk about places like subways as "non-spaces," spaces disconnected from anyone's life or world, but here the valley of the underground is more than exalted. The hours which the career-builder rejected may be the cornerstones of a godly life.

Monday, November 12, 2007

Friday, November 09, 2007

Religion kills

This teeshirt is sold at Revolution Church, a Pentecostal group with a Brooklyn branch (led by the son of the disgraced Jim and Tammy Faye Baker). I'm teaching my "Cultures of the Religious Right" course again this coming Spring, and am starting to look around for new material. Anthropologist Susan Harding, whose The Book of Jerry Falwell was an important part of the last iteration of the course, gave a talk here this week. It wasn't very good, but reassuring the way a not very good article on a subject you're researching can be reassuring: I'm on the right track, and am going farther than this person! Sorry if that sounds smug, but I came out of her talk and the ensuing discussion convinced all over again that religious studies is a necessary discipline - especially in these times!

This teeshirt is sold at Revolution Church, a Pentecostal group with a Brooklyn branch (led by the son of the disgraced Jim and Tammy Faye Baker). I'm teaching my "Cultures of the Religious Right" course again this coming Spring, and am starting to look around for new material. Anthropologist Susan Harding, whose The Book of Jerry Falwell was an important part of the last iteration of the course, gave a talk here this week. It wasn't very good, but reassuring the way a not very good article on a subject you're researching can be reassuring: I'm on the right track, and am going farther than this person! Sorry if that sounds smug, but I came out of her talk and the ensuing discussion convinced all over again that religious studies is a necessary discipline - especially in these times!

Cold snap

We had our first frost warning Wednesday night, and yesterday everyone was bundled up. (I'm holding out a bit longer before I bring out the scarves and hats and mittens.) The city feels suddenly colder not only because of the temperature but because people's winter coats tend to be in dark colors. All the colors bleach out of the human landscape just as the leaves disappear from the trees...

Wednesday, November 07, 2007

Upstaged by a sausage roll

I have learned that my sister and her boys had a close encounter with John Howard, the Australian Prime Minister, in a bakery in Gisborne recently; they seem to have survived unscathed. Apparently a short unattractive man came over, surrounded by cameramen and people holding big fuzzy mikes, and asked my older nephew his name. The answer was barely audible, as it was directed to my nephew's armpit - incontestably preferable to the creepy man with a wince where others have a smile. So the balding PM turned to my sister before making his way to a table of tea-drinking bikers. Bemused by the absurdity of it all, including the boys' savvy preference for sausage rolls over sleazy pols, my sister then had a nice chat with a shapeless woman who sat down at her table - and turned out to be Mrs. Howard! The story will be even better when it's about the ex-PM!

On another topic entirely, our Religion & Theater class has made it to Bertolt Brecht's Life of Galileo. To help students see that the play is not about "science and religion" in the 20th century American sense I drew on the board a telescope with the words DAS KAPITAL on it, under the caption "Brecht's telescope." Everyone admired my draughtsmanship, but none of the students knew what Das Kapital was. Lordy! (They do now.)

On another topic entirely, our Religion & Theater class has made it to Bertolt Brecht's Life of Galileo. To help students see that the play is not about "science and religion" in the 20th century American sense I drew on the board a telescope with the words DAS KAPITAL on it, under the caption "Brecht's telescope." Everyone admired my draughtsmanship, but none of the students knew what Das Kapital was. Lordy! (They do now.)

Tuesday, November 06, 2007

Efficient

Wow, to think that the Melbourne Cup just happened. It was won by an outsider named Efficient (a news factoid which begs to be deconstructed since the Melbourne Cup is so weighted as to make everyone an equally dark horse). As I recall, racing season was when Melbourne felt most foreign to me - all these people dressing up for the races, fancy summer dresses, summer suits and hats enough to employ a hundred milliners. Even my laid-back housemate Peter showed up in a top hat and tails! It feels even stranger to be recalling it just as we're sensing the onset of winter after a late fall (and in the aftermath of the New York Marathon).

This isn't the time to ruminate on "what Australia means to me" at this point - I'm going back for a fortnight in January, so I feel I can legitimately dodge the question with an appeal to unfinished research. But it's actually nice to be reminded of all the things Melbourne is which I didn't get: makes it feel more real! And as for Australia more generally, I'm still reading Australian books, at present two dramatically different novels which nevertheless somehow need to be brought into relation somehow: Mudrooroo's Doctor Wooreddy's Advice on Enduring the Ending of the World and Gerald Murnane's The Plains.

This isn't the time to ruminate on "what Australia means to me" at this point - I'm going back for a fortnight in January, so I feel I can legitimately dodge the question with an appeal to unfinished research. But it's actually nice to be reminded of all the things Melbourne is which I didn't get: makes it feel more real! And as for Australia more generally, I'm still reading Australian books, at present two dramatically different novels which nevertheless somehow need to be brought into relation somehow: Mudrooroo's Doctor Wooreddy's Advice on Enduring the Ending of the World and Gerald Murnane's The Plains.

This isn't the time to ruminate on "what Australia means to me" at this point - I'm going back for a fortnight in January, so I feel I can legitimately dodge the question with an appeal to unfinished research. But it's actually nice to be reminded of all the things Melbourne is which I didn't get: makes it feel more real! And as for Australia more generally, I'm still reading Australian books, at present two dramatically different novels which nevertheless somehow need to be brought into relation somehow: Mudrooroo's Doctor Wooreddy's Advice on Enduring the Ending of the World and Gerald Murnane's The Plains.

This isn't the time to ruminate on "what Australia means to me" at this point - I'm going back for a fortnight in January, so I feel I can legitimately dodge the question with an appeal to unfinished research. But it's actually nice to be reminded of all the things Melbourne is which I didn't get: makes it feel more real! And as for Australia more generally, I'm still reading Australian books, at present two dramatically different novels which nevertheless somehow need to be brought into relation somehow: Mudrooroo's Doctor Wooreddy's Advice on Enduring the Ending of the World and Gerald Murnane's The Plains.

Monday, November 05, 2007

Met melancholy

I've fallen behind again - had to spend Friday at a seminar on technology and liberal arts, which had the unintended consequence of keeping me from my computer!  (I did learn a few things about how to use new media in the classroom, though it wasn't worth spending a whole day on it.) So I didn't have a chance to tell you about:

(I did learn a few things about how to use new media in the classroom, though it wasn't worth spending a whole day on it.) So I didn't have a chance to tell you about:

• the Greenwich Village Hallowe'en Parade Wednesday night, our local carnival, Sixth Avenue thronged with people of all shapes and sizes in costumes, many handmade and very clever, a shapeless and joyful event although, by the end of it, you start looking even at people not in costume as if they're in costume!

• American Ballet Theater at City Center on Friday night, a gorgeous piece by Lar Lubovich called "Meadow" and an American classic I'd never seen, "Fall River Legend" (choreographed by Agnes de Mille to music by Morton Gould), which is a period piece - 1948 - but affected me powerfully. I felt I knew this world, from Copland and Barber, Our Town and even Oklahoma... what shock to bring an axe onto a ballet stage! (The story is loosely based on the story of Lizzie Borden.)

I felt I knew this world, from Copland and Barber, Our Town and even Oklahoma... what shock to bring an axe onto a ballet stage! (The story is loosely based on the story of Lizzie Borden.)

• my first big party: I fed eighteen people Saturday night, and people flowed easily through all four rooms of the flat, mine for a few more weeks. I was racing around like a madman opening the door, bringing out food (and then 9 cheeses), clearing away plates, opening bottles of wine, introducing people to each other. And I gather it was a "resounding success." Didn't have more than snatches of conversation with anyone, or fleeting gulps of wine (though I made sure to slow down around cheese time!), but by the end I was pooped and elated. I'm not sure why one has parties, really, but it felt like an offering, a gift to society, the world...

And yesterday I spent the afternoon at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, my first visit in over a year. There were no fewer than five special exhibitions I wanted to see - shameless showoff of a museum! The exhibitions were splendid, of course: (1) the Met's whole collection of Dutch masters, (2) baroque tapestries, (3) Central African reliquary objects presented for the first time (they claimed) as religious objects rather than just beautiful statues (pictures are from their site), (4) early photographs, and (5) three panels from Ghiberti's Old Testament door to the Battisterio in Florence, recently restored and at eye level. I also nipped into the Japanese collection and the Chinese, and at one point found myself in the new Roman sculpture court (where the cafeteria used to be). Overwhelming as ever.

Ghiberti's Old Testament door to the Battisterio in Florence, recently restored and at eye level. I also nipped into the Japanese collection and the Chinese, and at one point found myself in the new Roman sculpture court (where the cafeteria used to be). Overwhelming as ever.

The Met usually makes me melancholy, something about the extraordinary beauty of its vast collections, the worlds upon worlds of meaning it provides brief windows into - and the fact that every single piece found its way there because of money. (Unlike, say, the Louvre which benefited from conquests...) What was striking this time was that the role of money was front and center in many of the exhibits: we have truly entered a new Gilded Age, and the Met is clearly out to charm the new oligarchs and plutocrats. So, for instance, the Dutch collection was organized by date of acquisition, with rooms named after the benefactors. Half of the Japanese collection was devoted to recent gifts by named people, and the Chinese gallery anticipated a promised collection by an expatriate Chinese family. About Ghiberti and the tapestries we read about patronage and far-seeing benefactors for whom money was no object. And many of the African reliquary objects, we learned, had passed through the collections of great early-twentieth century artists (this exhibition protested a wee bit too much about the "universal" significance of these objects, their contribution to the "eternal" aspirations of humanity - they should have let them speak for themselves).

they should have let them speak for themselves).

I suppose it's a good thing to make the business of art and museums explicit... or is it? In any case, it is a change from the ethos of public and national museums with which I'm familiar, which offer a direct encounter of the viewer off the street and the art object, without reminders of questions of provenance. Now it feels like I'm an outsider to the whole process: not an artist, and not rich enough to commission or buy and donate artworks.

(I did learn a few things about how to use new media in the classroom, though it wasn't worth spending a whole day on it.) So I didn't have a chance to tell you about:

(I did learn a few things about how to use new media in the classroom, though it wasn't worth spending a whole day on it.) So I didn't have a chance to tell you about:• the Greenwich Village Hallowe'en Parade Wednesday night, our local carnival, Sixth Avenue thronged with people of all shapes and sizes in costumes, many handmade and very clever, a shapeless and joyful event although, by the end of it, you start looking even at people not in costume as if they're in costume!

• American Ballet Theater at City Center on Friday night, a gorgeous piece by Lar Lubovich called "Meadow" and an American classic I'd never seen, "Fall River Legend" (choreographed by Agnes de Mille to music by Morton Gould), which is a period piece - 1948 - but affected me powerfully.

I felt I knew this world, from Copland and Barber, Our Town and even Oklahoma... what shock to bring an axe onto a ballet stage! (The story is loosely based on the story of Lizzie Borden.)

I felt I knew this world, from Copland and Barber, Our Town and even Oklahoma... what shock to bring an axe onto a ballet stage! (The story is loosely based on the story of Lizzie Borden.)• my first big party: I fed eighteen people Saturday night, and people flowed easily through all four rooms of the flat, mine for a few more weeks. I was racing around like a madman opening the door, bringing out food (and then 9 cheeses), clearing away plates, opening bottles of wine, introducing people to each other. And I gather it was a "resounding success." Didn't have more than snatches of conversation with anyone, or fleeting gulps of wine (though I made sure to slow down around cheese time!), but by the end I was pooped and elated. I'm not sure why one has parties, really, but it felt like an offering, a gift to society, the world...

And yesterday I spent the afternoon at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, my first visit in over a year. There were no fewer than five special exhibitions I wanted to see - shameless showoff of a museum! The exhibitions were splendid, of course: (1) the Met's whole collection of Dutch masters, (2) baroque tapestries, (3) Central African reliquary objects presented for the first time (they claimed) as religious objects rather than just beautiful statues (pictures are from their site), (4) early photographs, and (5) three panels from

Ghiberti's Old Testament door to the Battisterio in Florence, recently restored and at eye level. I also nipped into the Japanese collection and the Chinese, and at one point found myself in the new Roman sculpture court (where the cafeteria used to be). Overwhelming as ever.

Ghiberti's Old Testament door to the Battisterio in Florence, recently restored and at eye level. I also nipped into the Japanese collection and the Chinese, and at one point found myself in the new Roman sculpture court (where the cafeteria used to be). Overwhelming as ever.The Met usually makes me melancholy, something about the extraordinary beauty of its vast collections, the worlds upon worlds of meaning it provides brief windows into - and the fact that every single piece found its way there because of money. (Unlike, say, the Louvre which benefited from conquests...) What was striking this time was that the role of money was front and center in many of the exhibits: we have truly entered a new Gilded Age, and the Met is clearly out to charm the new oligarchs and plutocrats. So, for instance, the Dutch collection was organized by date of acquisition, with rooms named after the benefactors. Half of the Japanese collection was devoted to recent gifts by named people, and the Chinese gallery anticipated a promised collection by an expatriate Chinese family. About Ghiberti and the tapestries we read about patronage and far-seeing benefactors for whom money was no object. And many of the African reliquary objects, we learned, had passed through the collections of great early-twentieth century artists (this exhibition protested a wee bit too much about the "universal" significance of these objects, their contribution to the "eternal" aspirations of humanity -

they should have let them speak for themselves).

they should have let them speak for themselves).I suppose it's a good thing to make the business of art and museums explicit... or is it? In any case, it is a change from the ethos of public and national museums with which I'm familiar, which offer a direct encounter of the viewer off the street and the art object, without reminders of questions of provenance. Now it feels like I'm an outsider to the whole process: not an artist, and not rich enough to commission or buy and donate artworks.

Thursday, November 01, 2007

Moving

Couldn't resist this story. The 13th-century Emmäuskirche in Heuersdorf, near Leipzig, has spent the last seven centuries on land which is now the target of mining. So it's being moved - all in one piece. Its new home is in a town called Borna, where it will occupy a square named after Martin Luther. The rest of the town seems slated for resettlement, too.

Couldn't resist this story. The 13th-century Emmäuskirche in Heuersdorf, near Leipzig, has spent the last seven centuries on land which is now the target of mining. So it's being moved - all in one piece. Its new home is in a town called Borna, where it will occupy a square named after Martin Luther. The rest of the town seems slated for resettlement, too.(Source of the picture and details on Heuersdorf's plight.)