The Old Testament reading this morning was from Genesis 17 where God renames Abram as Abraham, and Sarai as Sara. The sermon was about names, ending with the suitably unsettling question "What is God's name for you?" But it led us there by getting us to think about the names we already know - or think we do. The priest said that when working with groups she sometimes uses this as an ice breaker: tell us something about your name. We tried it over lunch, not expecting much, but it took off. Your name might seem like it's quintessentially yours, a fixed point, whether you like it or not, but say anything more about it and you're thinking about other people: namings, namers and their intentions, and the planned and unplanned places a given name takes you. Random factoid from my name story: my parents had Europe-specific reasons for calling me Mark, but lots of other American boys born the same year also wound up with that name. Indeed, I discovered at one point, that the mid-sixties were, in the US at least, peak Mark! As a result I don't meet many other Marks, but when I do, they're almost always around the same age as me.

Sunday, February 28, 2021

Saturday, February 27, 2021

Stations

Friday, February 26, 2021

Vibrant matter

Just started reading a fun new book and I think I'm in love. Mary-Jane Rubenstein works at the intersection of debates about science and religion, gender, theology and history of ideas but that doesn't begin to describe the remarkable synthesis of this book. Its topic is "pantheism," the abject of western tradition, maligned and vilified and yet, she shows, always present. Not that there's any consensus on what pantheism is, perhaps because it's defined as the monstrous and creative refusal to accept the distinctions on which western tradition is built - distinctions she shows are always gendered and racialized, and which have served to deny and repress the mystery and fecundity of an animate and pluralistic world. As variously denigrated communities have done with terms like "queer," "hag," "Obamacare," and "the big bang," the aim here is to reappropriate and mobilize a ridiculed position to disrupt the very order that finds it so revolting. (32)

Just started reading a fun new book and I think I'm in love. Mary-Jane Rubenstein works at the intersection of debates about science and religion, gender, theology and history of ideas but that doesn't begin to describe the remarkable synthesis of this book. Its topic is "pantheism," the abject of western tradition, maligned and vilified and yet, she shows, always present. Not that there's any consensus on what pantheism is, perhaps because it's defined as the monstrous and creative refusal to accept the distinctions on which western tradition is built - distinctions she shows are always gendered and racialized, and which have served to deny and repress the mystery and fecundity of an animate and pluralistic world. As variously denigrated communities have done with terms like "queer," "hag," "Obamacare," and "the big bang," the aim here is to reappropriate and mobilize a ridiculed position to disrupt the very order that finds it so revolting. (32)

This means starting with the "panic" (one of a panoply of Pan-related terms invited to the dance) which the idea of identifying God and the world has caused western thinkers over the centuries. This frenzy of rejection conceals a horror of multiplicity, mixture, indeterminacy - life! - and is articulated with dreary consistency in deadening hierarchies, distinguishing divinity - which is theistically encoded as immaterial, strictly active, anthropomorphic, light-soaked, and male - [from] matter, understood as passive, amorphous, dark, and feminine. (47) Yet Rubenstein's purpose isn't to liberate the world from the wielders of God-language but to rescue God, too, from the oppressive imaginations of the past. One past: as she shows the narrowness of the tradition she discovers new possibilities within it.

It's dazzling, the kind of work, I sense, which can change your life.

Thursday, February 25, 2021

Piled up

On my way to volunteering at Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen this morning I had time to pop into the new Penn Station "Moynihan Train Hall." Elmgreen & Dragset's "The Hive," high above the entrance on West 31st St., was all I had hoped and more; the rest, unfortunately, rather less. But at HASK we disassembled/reassembled 140 boxes of food!

Wednesday, February 24, 2021

That's Life

As you know, this week's theme in "After Religion" is "The invention of 'world religions.'" Last week we made our way through arguments that the idea of religion as a separate province of culture, distinctively personal and transcending history and politics, is a modern western contrivance. This week's task is to dismantle the mythology of world religions... that there are any such things! Great and complicated networks of transmission and practice exist, of course, but designating them "world religions" misdescribes them. Insisting that religion is, as Brent Nongbri puts it, "a genus that contains a variety of species, that is, the individual religions of the world, or World Religions" makes them seem both too similar and, perhaps, too different.

Our most diverting material was the special series of "picture essays" LIFE magazine ran on "The World's Great Religions" in 1955, touted as "a unique venture in journalism": Hinduism, The Path of Buddhism, Religion in the Land of Confucius, The World of Islam, Judaism and Christianity. The issues are conveniently digitized, allowing us not only to access them easily, but to encounter them as readers then will have, between other articles and, of course, sandwiched between glossy advertisements for cars, Jell-O, life insurance, girdles and tobacco. It was important to for me that the class discover them this way, because when you think about it, world religions are one of the most effectively packaged product lines of our time. Marx would smile: the series begins opposite a cigarette advertisement.

The rationale for the series is interesting. The time when people of the East thought Western thought crude, and Westerners thought the Eastern quaint, the proper concern of missionaries, is ending. Today nations which follow ancient religions are resurgent and ambitious and, in today's world, no nations are remote. It's valuable to understand the drivers of conduct in an increasingly uppity decolonizing world, and it can also be personally enriching. Returning more and more to the devout practices of their own faiths, Americans can re-examine and enrich their own spiritual life through the insights and intuitions of others. The voice comes through of a Christian missionary disappointed in India but energized in the struggle for man's soul against godless communism. That the world religions might all come to roost in the US is beyond imagining.

The rationale for the series is interesting. The time when people of the East thought Western thought crude, and Westerners thought the Eastern quaint, the proper concern of missionaries, is ending. Today nations which follow ancient religions are resurgent and ambitious and, in today's world, no nations are remote. It's valuable to understand the drivers of conduct in an increasingly uppity decolonizing world, and it can also be personally enriching. Returning more and more to the devout practices of their own faiths, Americans can re-examine and enrich their own spiritual life through the insights and intuitions of others. The voice comes through of a Christian missionary disappointed in India but energized in the struggle for man's soul against godless communism. That the world religions might all come to roost in the US is beyond imagining.

Each of the photo essays is gorgeous and interesting in its own way, resonating and contrasting with later images of the distinctive character of the world religions, but it's worth noting that the Christianity celebrated at the end is primus inter pares. The first five appeared monthly at the start of 1955, but Christianity appeared half a year later at Christmas in a glossy double issue - longer than all the rest combined. And when you look more carefully you see that the "World's Great Religions" series only ever comprised the first five. While there are symbols for all six on the programmatic opening page, the editors note that Christianity, the great religion of the West, will be the subject of separate and later treatment.

Lots of features of the world religions discourse can be discerned here, from the slippery status of Confucianism as a religion to the supposedly unchanged antiquity of Hinduism and Judaism to Islam's "missions" and "Buddhism's "conversion of Asia." While all confront modernity (and communism), Christianity alone seems to be in charge of its destiny - and so of the destiny of all. The book-length Christianity issue is full of scenes of revivals, processions, and men of the cloth ready for battle. Included is even a section of hymns, which prominently features the "Battle Hymn of the Republic."

The name of the week, "The invention of 'world religions,'" pays tribute to a book of that name by Tomoko Masuzawa, which argued that the apparently egalitarian array of world religions is really still European Universalism ... Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. This was a shocker in religious studies in 2005, which had worked within this schema as unthinkingly as the social sciences within secularization theory, but old news for my students in 2021. Not that the "world religions" carry any great promise for folks "after religion," but the notion that this might be a construct that serves to enthrone Christianity as king of kings surprises them not at all. Organized religion is all about supremacy - why they're after religion.

On the other hand, when I asked them in a google.doc whether they'd learned about religion in school, and/or if they think children should learn about "religion, spirituality and what comes 'after religion,'" they were all in. Variously myopic or truncated experiences gave them a strong of sense of how not to do it, but inculcating respect and tolerance of religious difference seemed a worthy and important goal. A few showed up for my "open office hours" where someone asked me what I thought, and was treated to a mini-lecture on Nell Nodding's Education for Intelligent Belief or Unbelief, which argues that school children deserve to be introduced to larger existential questions, but best if this is not in a separate course. They can arise organically in history and literature but also math and science and art classes.

None seemed as enthralled as I am by the Museum of World Religions in Taipei. One said its "sterile museum-type mode" reminded him of classes he'd had to take, from which he retained nothing. He may have read the organizers' hope that Entering the museum will be like entering a religious department store! But then I haven't confronted the class with how it might differ from western museums since it's part of "Avatamsaka World." Introducing them to that sutra's simile of Indra's Net (jewels each of which reflect all the others) might provoke some transformative wonder. World religions may be stale brands, but the different theologies of world religions might get things cooking!

Monday, February 22, 2021

Sunday, February 21, 2021

Whirled religions

The theme for "After Religion" this coming week is "the invention of 'world religions'" and one of the assigned course materials is a museum in Taiwan. 世界宗教博物館 claims to be the world's only Museum of World Religions and I'm hoping students brave the virtual tour. If they do they'll see this, looking back along the exhibition's central axis. It's a model of the cathedral at Chartres, and you can see reflected in the glass behind it some of the other Greatest Sacred Buildings represented, from the Dome of the Rock to a 9th c. Buddhist temple in Shanxi, Ise Jingu to the Golden Temple in Amritsar; if you turned around, you'd see a scale model of Borobodur, near the center of the room, and on the wall behind it a display of Taiwanese folk religion.

It's a model of the cathedral at Chartres, and you can see reflected in the glass behind it some of the other Greatest Sacred Buildings represented, from the Dome of the Rock to a 9th c. Buddhist temple in Shanxi, Ise Jingu to the Golden Temple in Amritsar; if you turned around, you'd see a scale model of Borobodur, near the center of the room, and on the wall behind it a display of Taiwanese folk religion.  The religious architecture display, united by what appears to be a stream of water flowing in a loop underneath the models, is elevated a little above the main exhibit which encircles it, with displays dedicated to a selection of world religions: on the side through which you enter the space Daoism, Shinto, Maya, Sikhism and Hinduism, on the other Christianity, Judaism, Ancient Egypt, Islam and Buddhism. A relatively standard set except for Maya and Ancient Egypt which,

The religious architecture display, united by what appears to be a stream of water flowing in a loop underneath the models, is elevated a little above the main exhibit which encircles it, with displays dedicated to a selection of world religions: on the side through which you enter the space Daoism, Shinto, Maya, Sikhism and Hinduism, on the other Christianity, Judaism, Ancient Egypt, Islam and Buddhism. A relatively standard set except for Maya and Ancient Egypt which,  while not represented among the monuments, mark the midpoints of the displays. (Here you see the Day of the Dead, presented as part of Maya, reflected in the vitrine of Ancient Egypt.) I'm hoping the layout here gets students thinking about how to think about religious plurality and how to represent it: I've learned from teaching with the Rubin Museum over the years that thinking about curating is a stimulating way to encourage analysis and synthesis. The most

while not represented among the monuments, mark the midpoints of the displays. (Here you see the Day of the Dead, presented as part of Maya, reflected in the vitrine of Ancient Egypt.) I'm hoping the layout here gets students thinking about how to think about religious plurality and how to represent it: I've learned from teaching with the Rubin Museum over the years that thinking about curating is a stimulating way to encourage analysis and synthesis. The most

observant might look at the whole museum, which has fun rituals built into the visit involving water and pilgrimage and handprints, and will notice that there is a particular theology of world religions organizing everything. Look again at the picture of Chartres above. The glass behind it reflects the world religions but you can also make out a round shape behind it. It's the heart of the building, a 3-story-high

suspended golden sphere called Avatamsaka World. (If it calls to mind the Hayden Planetarium at AMNH that's no coincidence; the same architectural firm designed both.) Visitors to the museum pass under this sphere as they enter, and walk past it on their way to the World Religions exhibit. The glorious Avatamsaka (Flower Garland, 華嚴 huayan/kegon) Sutra is centrally important to East Asian Buddhism, and definitely not what the western concocters of "world religions" had in mind! Do you suppose any of the students will look it up?

suspended golden sphere called Avatamsaka World. (If it calls to mind the Hayden Planetarium at AMNH that's no coincidence; the same architectural firm designed both.) Visitors to the museum pass under this sphere as they enter, and walk past it on their way to the World Religions exhibit. The glorious Avatamsaka (Flower Garland, 華嚴 huayan/kegon) Sutra is centrally important to East Asian Buddhism, and definitely not what the western concocters of "world religions" had in mind! Do you suppose any of the students will look it up?

Friday, February 19, 2021

Entwined

In other news, renovation of a tapas bar near the cathedral in Sevilla (taking advantage of covid-related closure) uncovered something remarkable. Their space, which they thought had been constructed in the neomudéjar style a century ago, is in fact the real deal: a Muslim bathhouse (hammam) built almost a millennium ago! It's stunning that the building, and so much of its ornamentation, should have been so sturdy as to have survived centuries of reuse and forgetting. (Brick and stone structures, I suppose, last longer than wood, and are harder to remove than to reuse.) I'm not sure why this find makes me so happy: the improbable survival of the distant past? the ways the past is present, hidden all around us, holding us even as we forget it? (well, in the old worlds; settler colonial societies bank on erasing the past.) Maybe it's the way Islamic geometric design seems to articulate just such beautiful patterns and mysteries?

In other news, renovation of a tapas bar near the cathedral in Sevilla (taking advantage of covid-related closure) uncovered something remarkable. Their space, which they thought had been constructed in the neomudéjar style a century ago, is in fact the real deal: a Muslim bathhouse (hammam) built almost a millennium ago! It's stunning that the building, and so much of its ornamentation, should have been so sturdy as to have survived centuries of reuse and forgetting. (Brick and stone structures, I suppose, last longer than wood, and are harder to remove than to reuse.) I'm not sure why this find makes me so happy: the improbable survival of the distant past? the ways the past is present, hidden all around us, holding us even as we forget it? (well, in the old worlds; settler colonial societies bank on erasing the past.) Maybe it's the way Islamic geometric design seems to articulate just such beautiful patterns and mysteries?

Thursday, February 18, 2021

Always relevant

Public Seminar has in the last week published not one but two installments of our newer truer history of The New School, reminders of the pleasures and challenges of understanding where you come from. A Relevant Education: The New School in the 1960s, an excerpt from a recently published memoir, offers a delightful account of being an undergraduate here during the counterculture. The joy and serendipity of learning in a community committed to offering a "relevant education" resonates with what people taking classes at The New School must have experienced here in every decade.

Reckoning with the New School's Legacies: A comprehensive view reveals entrenched inequities, by my historian co-conspirator J, shares what we've long known but too many don't: that the structures and mechanisms that provided this delightfully relevant educational world were far from delightful, supporting an expensive commitment to an elite corps of researchers with the poorly paid labor of armies of contingent instructors and an overworked staff. Most of today's debates on how we should move into the future don't realize the idealistic vision of the 1919 founders soon gave way to a series of quite different (also exciting) realities, only in the last few decades becoming university-like with significant populations of full-time degree-seeking students, faculty and staff. The institutional history of The New School has much to teach us, hard truths but relevant.

Midterm (in two weeks)

An exam is a way of showing students what they (should) have learned, and what they can do with it - content as well as ways of navigating and building on it. For the midterm paper in "After Religion," due the 7th of our 15 weeks (a mere fortnight from now!),

I provided more fully articulated prompts than I usually do in my seminars, where the open-endedness is part of the process. Students have to choose just one of these nine topics, but I hope they'll realize they've actually learned enough to address all of them.Wednesday, February 17, 2021

Lent tree

It's Ash Wednesday, the start of the season of Lent ... so we took down the Christmas lights! But didn't have the heart to say goodbye to our hardy tree. Seeing it slowly lose its needles might fit the penitential mood. It's still up because Lent starts early this year, but it's more than that. We never really left last year's Lent! Even if we could gather for the imposition of ashes, what ashes could we use? Traditionally they're made from the palms of the previous year's Palm Sunday.

It's Ash Wednesday, the start of the season of Lent ... so we took down the Christmas lights! But didn't have the heart to say goodbye to our hardy tree. Seeing it slowly lose its needles might fit the penitential mood. It's still up because Lent starts early this year, but it's more than that. We never really left last year's Lent! Even if we could gather for the imposition of ashes, what ashes could we use? Traditionally they're made from the palms of the previous year's Palm Sunday.

Tuesday, February 16, 2021

Other than religion

For years, when planning and revising the syllabus for "Theorizing Religion," the required course for our religious studies minors, I've felt there was something missing. A major argument of the class is that the modern western category of "religion" distorts the experience of non-western (and non-modern) peoples, and may even have been designed to do that. The world religions paradigm, despite its kumbaya veneer, does that too, registering and (to a degree) venerating as "religion" only those aspects of premodern and non-western traditions which resonate with what Tomoko Masuzawa calls "European universalism." If the modern western "religion" concept was so lousy, oughtn't I to be introducing alternatives from non-western and premodern traditions? The problem (beyond the very real limits of my reading) was baked in: if "religion" is a modern western thing, illegitimately projected onto cultures and traditions foreign to it, then there are no non-western or premodern analogs to turn to. Indeed supposing there are is just repeating the same mistake; assuming there must be counterparts to it reasserts the universality of the category of "religion" we claim we're trying to think beyond!

In "After Religion," I had just one class - our topic for the week is What is "religion" anyway? - to take a stab at these questions, but I made headway somehow! The time limits probably helped, as did the fact that this course isn't an introduction to the academic study of religion. But best of all were the readings I wound up assigning, two chapters from Brent Nongbri's Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept, and an essay on "Indigenous African Traditions as Models for Theorizing Religion" by Edward P. Antonio. (Students were also assigned a fab documentary about The Satanic Temple, but that's topic for another post.) Nongbri's a historian of the religions of the ancient (western) world, and his little book deftly demonstrates the many unfamiliar ways the word religio was used before modernity - there was no analog to the modern concept - and chronicles the emergence in the Renaissance and early modern period of the "modern notion of religion as an essentially private or spiritual realm that somehow transcends the mundane world of language and history (18), touching on Ficino, Bruno, Herbert of Cherbury, Bodin and Locke. But for most of my students, the European 16th and 17th centuries are ancient history.

More exciting and accessible was the careful argument of Antonio. Before discussing it (in my prerecorded lecture, trying to be animated but not overact), I held up Nongbri's book and the book where Antonio's essay appears, Religion, Theory, Critique: Classic and Contemporary Approaches and Metholologies, a literal door-stopper. More to the point, Religion, Theory, Critique's almost seven hundred pages include fifty-fifty six fine-print chapters on theory of religion of which only four are about "Religion beyond the West," one of which is Antonio's. (The others are, predictably, on the Arabic din, on the Chinese zongjiao, and on translation.) The myopia of my "Theorizing Religion" is, alas, par for the course. But Antonio's piece as a revelation.

Antonio is rightly leery of the question what African traditions can contribute to the western theory of religion. African traditions are immensely varied and the western theory of religion has routinely ignored all of them. And besides: there is no analog to the modern notion of religion. Any contribution would have to begin by insisting on the "otherness" of indigenous African ways to western theory. Most of what is theorized under “religion” can be theorized in nonreligious terms in African traditions (150).

Antonio is rightly leery of the question what African traditions can contribute to the western theory of religion. African traditions are immensely varied and the western theory of religion has routinely ignored all of them. And besides: there is no analog to the modern notion of religion. Any contribution would have to begin by insisting on the "otherness" of indigenous African ways to western theory. Most of what is theorized under “religion” can be theorized in nonreligious terms in African traditions (150).

The point cannot be to ground a new universal theory of religion in indigenous African traditions. The idea that there is such a thing as religion and that it is universal, the idea that underwrites the efforts of many scholars of religion to see religion everywhere, is largely a Western obsession. (149) Instead of a "theory" or "model" he suggests African indigenous traditions might illuminate as a "heuristic," a rough guide that aids the discovery of intelligibility and understanding in knowledge and interpretation (148). Writing in English (except for one reference to ubuntu), Antonio deflects from "religion" with the language of the everyday, common-sense, immanence, phenomenology, hermeneutics, pragmatism, anthropology and, most important, a "humanism" focused on persons, communities, hospitality and health and maintained by the indispensable work of divination whose ethically superior practitioners provide[e] a space for determining the preconditions of proper relationally and thus of what it means to be human (152).

When not explicitly or tacitly denying Africa has religion, or relegating its traditions to some "primal" category, western scholars note the embeddedness of "religion" in everyday social life and argue the significance of the "practice of everyday life" is entirely attributable to religion. Everything is sacred! Antonio suggests that this gets things back to front. Religious practices do not refer to phenomena outside the world (150). The immanent world of everyday social interactions is where everything happens, including not only the relationships that constitute us, but the equally significant practices of hospitality with "others," from ancestors to spirits. If the theory of religion were open to this "heuristic," Antonio brings it together, African religious traditions will have taught the study of religion the importance of privileging not gods, spirits, the cosmos, notions of salvation understood as the quest for the other world, and ritual as bizarre performance of inarticulable abjection, but humanity as the space of relational encounter with otherness in the fullness of all its variety—human, natural, and spiritual (153).

I love this, and have to stop myself from wanting to - yes - universalize it. Isn't this really what's going on even in those "religions" where people are convinced they are guided by "phenomena outside the world," think they can and should stand alone before the transcendent without any human aid or witness? It resonates with my long-standing efforts to characterize religion (sic) in terms of "wider moral communities." And yet, of course, Antonio is also saying that this is not a better, broader account of "religion," though it may describe interactions and relationships which theories of "religion" might appreciate. To learn from it I'll need to try to see whether "anthropological humanism" can satisfy my local as well as broader concerns, and if not, why not. And of course not to stop with the generalizations (and English terms) of his necessarily abbreviated article. Not in this class, but in the next "Theorizing Religion"!

Monday, February 15, 2021

CoronAsuras

It's tempting to forget that COVID-19 isn't nearly done with us.

This curve has only become more acute since the last time I showed it, January 8th, when we'd just reached 4000 souls lost in a day. Don't be fooled by the relatively low number of deaths listed here; Monday numbers are always artificially low because record-keeping is delayed on weekends; almost 9000 deaths were recorded the day before. And the total is 486,111 in the U.S. and 2,405,804 globally. Maybe we'd take it more seriously if we had traditions like the Javanese shadow puppet above or the Chhau dance from eastern India below to make the "CoronAsura" (both described here, with video links) real to us.Sunday, February 14, 2021

Benton back in New York

1957 is early days for complicating the narrative of European "discovery" of the Americas, but what Benton includes, based on extensive research, shows how much was known even then for those with eyes to see. The village portrayed is based on a 16th-century illustration of Cartier's observations, writes Scott Manning Stevens, Director of Native American and Indigenous Studies at Syracuse in the exhibition text. Benton was careful to depict the Iroquoian people as skilled agriculturalists tending their crops of corn, beans, and squash. The background of the mural on the right, where Cartier's men erect a cross on a beach, seems empty, but the scene at left is an already verdant settled world. Even the Cartier mural has as its focal point a basket of farmed vegetables, a generous abundance which contrasts with the skeletal rosary the Seneca chief takes gingerly from Cartier.

Saturday, February 13, 2021

Friday, February 12, 2021

Impeach!

The charade of a defense of Donald Trump at the trial for his second impeachment (the first time Senate Republicans decided they didn't need a trial) was shocking not just for its bad faith and vulgarity but for how brazenly it displayed Trump's domination of his party. In a court of law, which the Senate is not, threatening the jurors is unthinkable. Here we had his latest surrogates telling Republican Senators that if they did not vote to acquit, he would - as he's thuggishly threatened all along - set the hounds on them. This is how authoritarianism perverts a society, isn't it: nakedly.

Thursday, February 11, 2021

Never finished

Ventured out today to a gallery! (It was combined with another stint at the Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen and Food Pantry.) The show was called "Never Finished" and brought together works by Josef Albers and Giorgio Morandi. It's a curious juxtaposition but not without interest. I actually overheard the curator give someone reasons for pairing them, and he gave so many that they started to feel contrived. Most interesting, for me, is the way both artists play with - invite play with - two and three dimensions, all, needless to say, rendered conspicuously in just two. A Morandi show was one of the highlights of my year in Paris (twenty years ago!) - and since then I've felt I was encountering the dearest of old relations whenever I happen on even one of his canvases in a museum. This time was a little different, because of the cold vast spaces of the gallery, but probably also because of the intervening Albers, not (yet) one of my faves.

Ventured out today to a gallery! (It was combined with another stint at the Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen and Food Pantry.) The show was called "Never Finished" and brought together works by Josef Albers and Giorgio Morandi. It's a curious juxtaposition but not without interest. I actually overheard the curator give someone reasons for pairing them, and he gave so many that they started to feel contrived. Most interesting, for me, is the way both artists play with - invite play with - two and three dimensions, all, needless to say, rendered conspicuously in just two. A Morandi show was one of the highlights of my year in Paris (twenty years ago!) - and since then I've felt I was encountering the dearest of old relations whenever I happen on even one of his canvases in a museum. This time was a little different, because of the cold vast spaces of the gallery, but probably also because of the intervening Albers, not (yet) one of my faves.

Wednesday, February 10, 2021

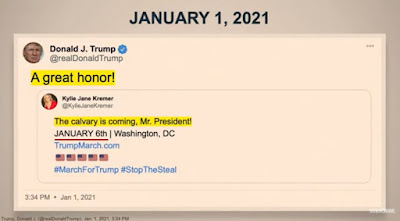

Calvary is coming

I've been watching some of the impeachment trial today, the expertly made case that Donald Trump knowingly incited an insurrectionist mob on January 6th - a mob he had created and cultivated by his big lie about election fraud over months, indeed years. It was shocking to remember that he had been planning to hold on to office despite losing from long before November 3rd, and then to follow through the depressing series of legal and extralegal methods he explored after it. But it was shocking also to see affront after affront after affront lined up. Only now that he is out of office have things calmed enough that we can focus on them; while he was president he was in constant motion, interrupting reckoning with each violation of a norm by an even more brazen violation of another.

I've been watching some of the impeachment trial today, the expertly made case that Donald Trump knowingly incited an insurrectionist mob on January 6th - a mob he had created and cultivated by his big lie about election fraud over months, indeed years. It was shocking to remember that he had been planning to hold on to office despite losing from long before November 3rd, and then to follow through the depressing series of legal and extralegal methods he explored after it. But it was shocking also to see affront after affront after affront lined up. Only now that he is out of office have things calmed enough that we can focus on them; while he was president he was in constant motion, interrupting reckoning with each violation of a norm by an even more brazen violation of another.

Now there is distance to see them line up. The chaos was targeted. So should we have seen it coming? Perhaps. He'd refused to commit to accepting defeat already in 2016, and worked tirelessly to undermine confidence in the government, its structures and its people. He indulged violence among his supporters, rhetorical and real. His words to the Proud Boys, "Stand Back and Stand By," immediately became their new slogan. When a motorcade of his supporters tried to drive a bus of Biden staff off a road in Texas - remember that? - he tweeted "I love Texas." And on and on. And as one effort to bend the rules after another failed, after enough state Republicans resisted his pressure to disenfranchise their voters, there was always January 6th. I know I felt queasy the weeks leading up to it, knowing something would happen, probably violent (and those hundred-plus Representatives and Senators who, even after the ransacking of the Capitol, voted to reject electoral votes didn't disappoint). I knew at the time that I was in denial, but stayed in denial. I trusted that Trump was fading away with his cancelled twitter noise, but had a harder time imagining what his most ardent followers - encouraged by people up and down the Republican Party in questioning the election's validity - would do.

The story being told by the impeachment managers leaves out the complicity of Republican Senators - they're jurors for the case who might, at least in principle, be swayed by the evidence - but it's plenty depressing. The likely outcome - acquittal, thanks to these Republicans' indifference, intimidation or acquiescence in an understanding of politics as war - is depressing, too. But meanwhile, wow. Our republic was in grave danger. Still is. The calvary is coming, Mr. President, tweeted the semi-literate leader of Women for America First, and he thrilled to the old-fashioned image of a decisive turn in the tide of battle. The cavalry!! Or maybe "calvary" wasn't a typo. His devotés didn't know what to expect of January 6th either, just something "historic" of which they wanted to be part. As it turned they saw their idolatrous cause crucified, but many still expect resurrection.

(White) (Christian) (America)

Pulling together the lectures for my course "After Religion" is proving more difficult than I anticipated. Part of the reason is surely the discombobulation of zoom lecturing. Especially if you make use of slides, links to videos and other online materials such as google.docs, it's more than one compute desktop can accommodate ... and even if you use none of those, you can't see more than a handful of the students in the class, immobilized in their zoom boxes. Having to switch computers in midstream surely didn't help, and my printer's run out of ink so I've been reading my notes from a phone!

Starting this week things are worse, or perhaps better: I'm setting aside the class time to meet students for small discussions, and circulating a prerecorded lecture beforehand. Prerecording makes the technical transitions easier - you can just pause your recording as you switch from sharing one thing to another, adjusting settings as needed - but the pretense that this is some sort of live communication, a site for connection, is lost. How do you know if anything you've said has gotten across? The temptation is to let the slides take over, hiding in a little box, or even closing that box, and becoming a voice-over. Writing the whole thing out is next, I suppose.

But these lectures are hard also because it's material I haven't lectured about before, and because it involves questions I haven't found answers for. This sort of subject matter is perfect for a seminar, but a lecture - especially the disembodied zoom lecture - demands a performance of certainty. On "spirituality" (especially of the "spiritual but not religious" kind), the topic of the last two weeks, it wasn't so hard. But this week's topic is "(White)(Christian)(America)" - the parentheses forming the question if and how these are related or even interdefined - and its central question the mystery of the Trump-supporting White Evangelical. There's heaps of material here but synthesizing it proved daunting. For one thing, not all Evangelicals are white, and not all Evangelicals supported Trump - though the white ones overwhelmingly did. For another, the majority of white Christians of all sorts voted for Trump in both elections, though not by majorities quite so large, and smaller than in 2016. But there's also the fact that I, too, am a White American Christian. When I showed video of thugs loudly praying in the Senate Chamber during the attack on the U. S. Capitol (starting at 8:00 here) I felt I had to say "they look like me, I look like them."

But, I said, appalled though I am by them and by the legions of others who think White Christian America is God's plan, I also have to speak as a scholar of religion, and it's not my business to call these false Christians. I shared a clip from a radio interview the Rev. William Barber gave (4:57-10:00 here), in which he reclaims the words "Evangelical" for the evangel, for the good news preached to the poor (Jesus' first words in the oldest gospel), and denounces white Evangelicals who celebrate wealth and ignore the poor as "heretics" involved in "theological malpractice." As a Christian, I said, I completely agree with him, but as a scholar I have to take into account all who understand themselves to be Christian, William Barber - but also William Barr.

Monday, February 08, 2021

年兽看到了!

While everyone was watching the Super Bowl (or at least Super Bowl ads) I watched a short Chinese New Year film produced by 苹果中国 - Apple China - patiently making my way through the subtitles. (My Mandarin listening comprehension is alas still pretty lousy.) It tells a sweet and sweetly predictable story about a little girl growing up in the mountains, warned against the niánshòu 年兽 (a wild beast) by her parents. She ignores them, of course, and becomes besties with the creature, even as her father keeps warning that it eats little children. She's unmoved when he explains (above) that he tried to make her believe those stories to protect her. 让你把故事当真,是为了保护你!

While everyone was watching the Super Bowl (or at least Super Bowl ads) I watched a short Chinese New Year film produced by 苹果中国 - Apple China - patiently making my way through the subtitles. (My Mandarin listening comprehension is alas still pretty lousy.) It tells a sweet and sweetly predictable story about a little girl growing up in the mountains, warned against the niánshòu 年兽 (a wild beast) by her parents. She ignores them, of course, and becomes besties with the creature, even as her father keeps warning that it eats little children. She's unmoved when he explains (above) that he tried to make her believe those stories to protect her. 让你把故事当真,是为了保护你!

A few years pass, and one year the girl decides to take the beast with her to the village new year's festivities - fine until the fireworks send it running away in terror. (Many new year's traditions are about frightening off scary monsters with light and sound and even the color red.) She runs after it to assure it there's no danger but her parents drag her home. She sneaks out the window into the mountain as the mother starts to wonder if they've been wrong: are the fireworks really there to scare away monsters and not, in fact, to light up the places in the mountains we want to go? 真的是为了赶走那些怪物吗?还是为了照亮山那边,那些我们想去的地方。 What are you really trying to protect her from, she asks her husband. I'm afraid of her growing up, he says, that this house won't hold her. 我怕孩子长大了,这个家留不住她。 I'm afraid that one day we won't be by her side. The more fearless she gets, he says, the more afraid I become. 我怕总有一天,我们会不在她身边。他越是天不怕地不怕,我就越怕。

But something's opened up. Next thing we see the family together going into the mountains to find the nián, and with the closing credits we're treated to the inevitable Chinese New Year scene of a family eating together around a table in their home - including not only the nian but both of the actresses who played the daughter, as a little girl and older! What's this all about? Nián 年 shares a character with the word year (or new year), and every new year's story is a version of "Sunrise, Sunset" from Fiddler on the Roof: change is less frightening than we think - and in any case can't be stopped. But this is an advertisement for Apple (the Apple logo appears at the end as a cute monster face), though there's no electronic device in sight in this rustic village. Or is about Apple, the American company? Fear not!

But something's opened up. Next thing we see the family together going into the mountains to find the nián, and with the closing credits we're treated to the inevitable Chinese New Year scene of a family eating together around a table in their home - including not only the nian but both of the actresses who played the daughter, as a little girl and older! What's this all about? Nián 年 shares a character with the word year (or new year), and every new year's story is a version of "Sunrise, Sunset" from Fiddler on the Roof: change is less frightening than we think - and in any case can't be stopped. But this is an advertisement for Apple (the Apple logo appears at the end as a cute monster face), though there's no electronic device in sight in this rustic village. Or is about Apple, the American company? Fear not!

Sunday, February 07, 2021

Frosted trees

The latest blizzard was lovely, turning our trees into frosty wonders

Best of all it subsided earlier than predicted, allowing an outing

in time to catch the icing before it blew off... and the sunset light!

A year of death

A year ago today, February 6th, the first known soul was lost to covid in the United States. Four hundred sixty-two thousand more have since lost their lives. In just one year. I can't make the number real.

I was tracking its spread in China a year ago "from the safety of New York," at a time when a thousand deaths seemed catastrophic. "This looks to me like something which might end up in every Chinese life story," I wrote, not conceiving it might turn out to be so globally.

There are reasons to be hopeful. We again have a government doing what government is supposed to be doing, thinking about the public good and marshaling resources to care for it. But the time squandered and the deaths which might have been prevented boggle the mind.

Friday, February 05, 2021

Sports of nature

Thursday, February 04, 2021

In the bag

On a beautiful day, I headed down to the Church of the Holy Apostles to volunteer at the soup kitchen and food pantry, my first time in a long time, and first time since covid-19. In the first of three shifts, about a dozen of us combined food from boxes of government aid with fresh produce of our own to fill 220 (!) sets of heavy bags of dry goods, produce, and protein: materials for thousands of meals. Another set of volunteers in another room filled snack bags to supplement the hot meals being distributed from the church door, and a third group will help distribute the bags we assembled. It was more physical labor than I've done in a year - not to mention laboring together with other people in an accelerating assembly line that reminded me of Charlie Chaplin's "Modern Times"!

On a beautiful day, I headed down to the Church of the Holy Apostles to volunteer at the soup kitchen and food pantry, my first time in a long time, and first time since covid-19. In the first of three shifts, about a dozen of us combined food from boxes of government aid with fresh produce of our own to fill 220 (!) sets of heavy bags of dry goods, produce, and protein: materials for thousands of meals. Another set of volunteers in another room filled snack bags to supplement the hot meals being distributed from the church door, and a third group will help distribute the bags we assembled. It was more physical labor than I've done in a year - not to mention laboring together with other people in an accelerating assembly line that reminded me of Charlie Chaplin's "Modern Times"!  It's important work and I was happy of a chance to contribute - covid permitting I plan to make it a regular thing in the next months.

It's important work and I was happy of a chance to contribute - covid permitting I plan to make it a regular thing in the next months.

Wednesday, February 03, 2021

Peeling the clementine

I tried Thich Nhat Hanh's tangerine-eating exercise with a large zoom class today. I think it worked, if only as a way of breaking the zoom routine: five minutes during which I asked them to turn cameras off but leave microphones on. I'd sent a reminder to students on Monday to get hold of a tangerine, clementine or other fruit, and then nearly ended up without one myself because of the blizzard! A few students told me they used apples and it was fine.

I tried Thich Nhat Hanh's tangerine-eating exercise with a large zoom class today. I think it worked, if only as a way of breaking the zoom routine: five minutes during which I asked them to turn cameras off but leave microphones on. I'd sent a reminder to students on Monday to get hold of a tangerine, clementine or other fruit, and then nearly ended up without one myself because of the blizzard! A few students told me they used apples and it was fine.

What does it mean to eat a tangerine in awareness? When you are eating the tangerine, you are aware that you are eating the tangerine. You fully experience its lovely fragrance and sweet taste. When you peel the tangerine, you know that you are peeling the tangerine; when you remove a slice and put it in your mouth, you know that you are removing a slice and putting it in your mouth; when you experience the lovely fragrance and sweet taste of the tangerine, you are aware that you are experiencing the lovely fragrance and sweet taste of the tangerine. The tangerine Nandabala offered me had nine sections. I ate each morsel in awareness and saw how precious and wonderful it was. I did not forget the tangerine and thus the tangerine became something very real to me. If the tangerine is real, the person eating it is real. That is what it means to eat a tangerine in awareness.

The aim of the exercise was to make our synchronous time together real - embodied and connected, transcending zoom distance by leaning into it. If a tangerine is really the sun, the water, the tree, the garden, the gardener, the supermarket, perhaps we're more connected than we seem.

But Thich Nhat Hanh's mindful tangerine-eating is also discussed in one of the assigned materials for class today, Andrea Jain's Peace Love Yoga: The Politics of Global Spirituality, and not favorably! Jain rejects the blanket dismissal of mindful practices as capitalist distractions from and for further capitalism, but she takes as given that many practices promising to cultivate awareness, presence, etc. take the place of engagement with the problems of the world that they purport to connect us to. "Neoliberal spirituality," she argues, participates in a "governmentality" which rejects structural analysis and intervention, making individuals responsible for their own fates even in circumstances beyond their control. Claiming to maximize individual freedom, it instead permits us to ignore the claims of others: they're to blame for their misfortunate, as they're not trying hard enough to change.

For all of the peace and love it offers through yoga, health foods, mindfulness, and countless other commodities, neoliberal spirituality plays a divisive, capitalist, and sometimes right-wing game that thrives on nostalgia about lost cultural norms, demarcating outsiders, questing after purity and policing morality, as well as on narratives about self-care, personal improvement, and the pursuit of freedom. (45)

There are lots of other ideas here, too, which I tried to discuss - the role of "nostalgia about lost cultural norms" plays in contemporary culture will be a major theme going forward - but I found myself (or so it seemed to me) waffling. Appropriation of practices variously packaged as ancient, Asian, indigenous, natural are appalling in lots of ways, but what alternatives are there? The "authentic" traditions so cruelly bowdlerized by shopping-cart spirituality are constructions, too, whether constructed by tut-tutting scholars, self-aggrandizing gurus, ethnonationalist movements or savvy marketers.

[W]hen observers, scholarly or otherwise, assume that there is an original, authentic tradition to be preserved, they produce yet another representation that is out of touch with reality. In other words, these approaches mirror in problematic ways the essentialist arguments of spiritual consumers themselves. They reify other traditions in ways that simplify them and make them easier to contain, own, discuss, and sell. (87)

Jain is too kind to point out that many "religions" today are involved in the same games, too, conveniently playing into neoliberal understandings of religion as truest when it is centered somewhere other than in the shared struggle of the here and now. (Next week's topic is white American Christianity...)

So what do we do?

[I]t is more constructive to focus on understanding how appropriating practices and relevant discourses buttress dominant ideologies and social structures, for example, neoliberal capitalist ones, while silencing or containing others, especially those resistant or alternative to the dominant ideological or socioeconomic orders (87)

This is, needless to say, more easily said than done, since, in a way, everything is open to question. We live in history, and so do the traditions and practices which we think might give us an escape from or at least a view beyond it. Though it's important to appreciate how contemporary flows of media, people and markets have turbocharged things, folks have been containing, owning discussing and selling religion all along. This is part of what the turn to "lived religion" has long emphasized: it's alive, changing, fluid, contested. So what's new? The explicit disaffiliation not only from particular religious traditions but from religion tout court? The seeking, and finding, of religious sustenance in similarly disaffiliated places?

I guess I bring more suspicion of "spirituality" than of "religion" (showing my age!), but it's helpful to share the suspicion I perhaps too quickly feel for the one, the generosity I too quickly feel for the other. Maybe Thich Nhat Hanh can help.

Do not think the knowledge you presently possess is changeless, absolute truth. Avoid being narrow-minded and bound to present views. Learn and practice nonattach-ment from views in order to be open to receive others' viewpoints. Truth is found in life and not merely in conceptual knowledge. Be ready to learn throughout your entire life and to observe reality in yourself and in the world at all times.

I was peeling the tangerine without knowing I was peeling it...