The museum itself is beautifully put together, telling with precision and poetry - Des paysages réels et imaginaires nous habite/ real and imaginary landscapes inhabit us - the difficult history of the Wendake people, who were driven here by intertribal conflicts from a homeland near Detroit as European-borne disease and French traders and missionaries arrived in these parts. (Another community of Wendak are now in Oklahoma.) The Wendake were "sold" this land by French Jesuits in 1760 in a contract only rediscovered in the 1990s.

In a special exhibition space we got to see the eeries images of "Mémoires Ennoyées," created by Ludovic Boney for the Québec Biennial earlier this year. Based on data from a sonic bathymetric echo sounder, its video and stills show the forest still standing in two reservoirs built in 1969 in the remains of the Manicouagan meteorite crater, their tops swaying in the current as once they did in the wind.Thursday, June 30, 2022

Standing

Wednesday, June 29, 2022

Père de l'Amérique Française

It's been a while since I last visited Québec - 17 years! - and I was disappointed to learn that the place I found most diverting then - the Musée de l'Amérique Française, now known as the Musée de l'Amérique Francophone - is only open on weekends. No matter. The chapel to François de Laval (1623-1708), designed in 1993 for Québec's Basilica-Cathedral of Notre Dame, reproduces most of the map I found so délirant on the floor of the Musée. (Laval was beatified in 1980, canonized in 2014, but the map takes you back to late 17th century.) Here is a continent designated Nou[vell]e FRANCE. The only discordant note is a little corner in the northeast, Nouvelle Bretagne.

Québec seems all about the subjunctive contained here, a North America which need not have become anglophone, with just a little pocket of francophones in a northeastern corner! Tongue-in-cheek inversion of what actually happened? I was wittier in 2005, noting crisply in my diary that Québec was the "tip of the long since melted iceberg of Amérique Française." Of course the continent need not have been invaded by European saints and sinners at all. Tomorrow we learn more about the First Peoples of this area.

Québec seems all about the subjunctive contained here, a North America which need not have become anglophone, with just a little pocket of francophones in a northeastern corner! Tongue-in-cheek inversion of what actually happened? I was wittier in 2005, noting crisply in my diary that Québec was the "tip of the long since melted iceberg of Amérique Française." Of course the continent need not have been invaded by European saints and sinners at all. Tomorrow we learn more about the First Peoples of this area.

Tuesday, June 28, 2022

Monday, June 27, 2022

Hors-pays

We're going on a long-planned road trip to Québec City - our first interna-tional travel in two and a half years! But heading to Canada at this point feels like fleeing the chronically unjust United States, as we wait for the rest of the weaponized Supreme Court's rulings undermining rule of law to fall. These trees, barely recognizable under monstrous vines which may well end up killing them, lined the road as we set forth.

We're going on a long-planned road trip to Québec City - our first interna-tional travel in two and a half years! But heading to Canada at this point feels like fleeing the chronically unjust United States, as we wait for the rest of the weaponized Supreme Court's rulings undermining rule of law to fall. These trees, barely recognizable under monstrous vines which may well end up killing them, lined the road as we set forth.

Friday, June 24, 2022

Chamber of horrors

Thursday, June 23, 2022

Gundamentalism

I learned a new term a few weeks ago, "gundamentalism," coined by Presbyterian pastor James Atwood a decade ago. An excerpt, quoted by Diana Butler Bass:

Many modern-day shamans and religious gun enthusiasts proclaim God wants all citizens well armed so they can protect our values, even our faith. . . These religious cults have become an integral part of the religion of the Gun Empire that give the idols of power and deadly force what they most need: a divine status. For these men and women the command to love God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength and your neighbor as yourself, is placed right alongside their new commandment to be ready at all times to defend yourself against your neighbor. . . (They) built an idolatrous religious framework around guns and have worked feverishly to justify biblically their unwarranted fascination with guns. . . Millions worship at this shrine.

Atwood, America and Its Guns: A Theological Expose, 82-83; qtd The Cottage

Bass and Atwood were responding to the American subculture which brandishes Bibles and guns together with no sense of contradiction, something which has been, frankly, incomprehensible to me. An opinion piece by Peter Manseau in this morning's Times, provoked by the explicitly Christian identity of the company which manufactured the assault weapon used to such lethal effect in that elementary school in Texas, argued that many gun owners believe in their guns, and that American gun culture is explicitly Christian. This is part of white Evangelical religion specifically. Most other Christian denominations discourage gun ownership and there seems in fact to be a negative correlation between religious participation and gun ownership. Even among Evangelicals: those most gun-idolizing are those who don't regularly attend worship. But, Manseau argues, the disagreement is at root a religious one. Referencing Paul Tillich's idea of "ultimate concern," it's about the most basic ideas about the way the world is and what matters. To many gun nuts, the world is a battlefield, with Jesus calling us to join his battalion. Manseau concludes

My view is closer to Abbott's fury. Those who believe in guns - who believe that individuals have the right to wield lethal force - seem to to me in thrall not of a religion but of something different and worse, idolotry, even something demonic. Tillich's concept of religion includes a demonic (and he'd agree that much of Christian history is demonic) but Manseau isn't spelling it out, concerned as he is with defending good religion against this bad one. Usually I err in his irenic direction.

But then we get today's latest attack on the common good from the conservative justices of the Supreme Court (all six!), subscribers to another kind of gundamentalism. Their dogmatic interpretation of the Second Amendment is absurd, as clear a case of reading an "unelaborated" right into the Constitution as you can ask for. ("Well regulated militia" - hello?!) It's a sign of the craven soullessness of originalism, kin to the self-righteous dishonesty of biblical fundamentalism.

I have not read the ruling, but it doesn't seem that it allows for any countervailing right not to be shot, let alone to feel safe. How many of these constitutional gundamentalists are also religious gundamentalists? And, yes, in thrall to the demonic?

Tuesday, June 21, 2022

聊天

Don't inhale?

Sunday, June 19, 2022

A fragile handful dangles gently

Just as the Duolingo dialogues with characters who just happen to be queer (most recently Bea mistakes someone she sees in the store for an ex-girlfriend, and Bruno and Héctor disagree about a song which played on their first date thirty years ago) delight me with their normality, I'm loving Queer Nature, an anthology of poems by 200 poets past and present. My first foray introduced me to Judith Barrington's "The Dyke with No Name Thinks about Landscape," whose last stanza, after love, terror and other experiences with people in natural settings, goes like this:

Just as the Duolingo dialogues with characters who just happen to be queer (most recently Bea mistakes someone she sees in the store for an ex-girlfriend, and Bruno and Héctor disagree about a song which played on their first date thirty years ago) delight me with their normality, I'm loving Queer Nature, an anthology of poems by 200 poets past and present. My first foray introduced me to Judith Barrington's "The Dyke with No Name Thinks about Landscape," whose last stanza, after love, terror and other experiences with people in natural settings, goes like this:

6

Now she is lying on a blanket, the sand below

moulded to the shape of her body.

Sudden swells lap the shore beyond her feet:

a barge has passed by.

trudging down river with its load

like a good-natured shire horse

its throbbing lost now behind the breaking

of that great wave which seems to rise from the deeps.

The turbulence is quick: a lashing of the sand

followed by September’s lazy calm

as the river moves unseen again,

cows from another world low on the far shore

and the seagull’s body, a fragile handful,

dangles gently between its two tremendous wings.

The trouble is not nature, she thinks

But the people who say I’m not part of it.

They’re trying to paint me out of the landscape

says the dyke with no name

but her thighs in hot sand remember a horse’s warm back

as the wind makes a great wave from Oregon to Beachy Head.

Saturday, June 18, 2022

Friday, June 17, 2022

Coup attempts past and present

Thursday, June 16, 2022

多儿鼓励我们从不放弃学习

I'm back to daily conversations in Mandarin (with my teacher in Oslo (go figure!). This past year, with too many classes and too much back and forth between in-person and virtual life, it was on the back burner. I tried to give it the occasional stir with apps, including - inspired by a friend who had recovered his German with it - Duolingo. I raced through its Mandarin only to reach the limit: only four levels.

Most frustrating, especially as I paid for a year's subscription. 怎么办? I decided to try out the Spanish, just for fun. I've never properly studied that language, so it's a better test of the Duolingo method, too. So far so good, but I'm also envious. Not only are there, surely, many levels, but Duolingo Español is full of clever dialogues; Chinese has none.... And even if it did, would they be as worldly and witty?This appears in "La Luna de Miel," in one of the first sets of stories.Tuesday, June 14, 2022

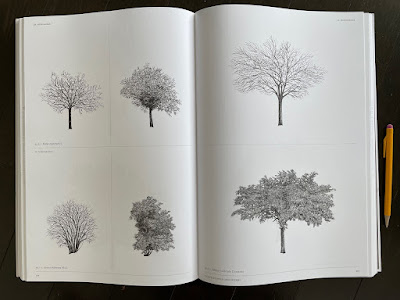

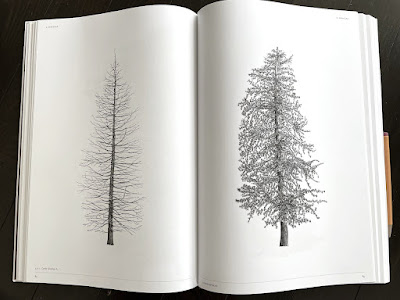

Davidia involucrata

As I showed a random page of a very large book I've recently received on Interlibrary Loan, The Architecture of Trees, to my Chinese tutor in Oslo (!), she said: "左边的是不是handkerchief tree!" Indeed it is! Not for nothing did she recently complete a virtual course in botanical illustration from a Botanical Garden in Scotland. The tree, rarely seen in European gardens, originated in China. The rather gorgeous book, with 1:100 pen drawings by Cesare Leonardi and Franca Stagi of over 500 trees, was originally published in 1982 but newly reedited for the English translation. A few more spreads (with my pencil for scale): And two glimpses of the larger apparatus - a representation of the shadows cast by a tree in Rome at different times of the year, and one of the relative sizes and colors of trees across the four seasons.

As I showed a random page of a very large book I've recently received on Interlibrary Loan, The Architecture of Trees, to my Chinese tutor in Oslo (!), she said: "左边的是不是handkerchief tree!" Indeed it is! Not for nothing did she recently complete a virtual course in botanical illustration from a Botanical Garden in Scotland. The tree, rarely seen in European gardens, originated in China. The rather gorgeous book, with 1:100 pen drawings by Cesare Leonardi and Franca Stagi of over 500 trees, was originally published in 1982 but newly reedited for the English translation. A few more spreads (with my pencil for scale): And two glimpses of the larger apparatus - a representation of the shadows cast by a tree in Rome at different times of the year, and one of the relative sizes and colors of trees across the four seasons. This seems to be a book for landscape architects, offering yet another way to think about trees in time and space and combination...

Monday, June 13, 2022

Tree revelations

When I threw together the course description for "Religion of Trees" I didn't quite know what the course could be about - just that it would be fun, and bring together things students and I are interested in. Now a few weeks into reading more deeply around trees I can feel the course taking a different shape than I'd dimly imagined.

What had I dimly imagined? That we'd look at trees in world religions, noting similarities and differences. Similar would be verticality if not quite Eliade's axis mundi, differences might emerge from comparing world trees and trees of life with the gnarled survivors of Zhuangzi. But all the trees I imagined were sublime - vastly larger or older than human beings, images of transcendence rooted in the depths of the earth and reaching to the sky, sheltering us. (I've yet to scope out the Bodhi tree and if it plays any such role.) We'd turn then to new tree science, perhaps by way of the tree of life in the Book of Revelation, which manages not only to offer all manner of fruits and healing herbs but to be on both sides of a river - a nod toward the subterranean networks and relationship of trees, as Catherine Keller has suggested? The parts of trees our visual imagination fixes on are hardly the most important (emblematic our attachment to leaves which change color just as they cease to serve a purpose for the tree).

I suppose my thinking began to change when I decided the class might incorporate tree drawing, and imagined a sequence of lessons: draw how you imagine a tree, then some actual trees, then some tree architectures, then eventually root systems and forests connected by mycelial webs. Along the way we'd consider how each of these might offer different religious morals. As we became more enmeshed with actual trees we might start learning something from them, perhaps that God is like the "mother tree" of a forest (as Process theologian Jay McDaniel has suggested), perhaps that everything is sentient and so interdependent. Along the way we might notice ways in which we - individually (sic), collectively - are more treelike than we imagined...

But the tree drawing, I discovered on trying my hand at it, is hard! And some of the philosophers and literary folks who write about plants and trees are goofy. While enjoyable, accounts of hearing the voices of trees after a "diet" of tree bark, etc. left me cold. (Must everything be psychedelic?) The more I read the less convinced I was that the myriad and marvelous forms of aborial sentience and communication being revealed by scientists (and ingenious artists) had anything to do with, or to say to, us. Call me a skeptic; part of what speaks to me about trees is that they don't speak to us, or speak (in some very broad sense of the term) but not to us.

Then I happened on William Bryant Logan's Sprout Lands, a work framed by the challenge of pollarding London plane trees in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (at top is a picture I took of one of them this morning) and finding nobody to turn to for help. Logan's an arborist and a poet, who thinks the heart most illuminated when in harmony with the hands. His book takes apart the idea that humans have ever had relationships with trees which didn't involve working with them - cutting, pruning, grafting... This was no less true of trees in woods than in orchards or gardens; indeed that contrast falls apart too. Our image of stately trees with clean lines are the result of English post-enclosure ideals. In the new picturesque landscape, man became the spectator of an idea of nature that he himself had made in the image of a primordium that had never existed (29). None of the world's "wild" forests - even the Amazon! - weren't in fact shaped by human beings. Logan suggests we think of woodlands as like lichens, the symbiotic work of trees and humans. Our icon of a tree should be the spray of a copse or the knuckles of pollarded trees.

So those images of stately transcendent tree solitaries are not so venerable after all! Our ancestors knew trees in quite different ways. More than a few of those ways resonate with things discovered (sic!) by botanists, and all involved enfleshed relationships with our arborial kin - Kimmerer's work remains indispensable here. What does this mean for a course called "Religion of Trees"? For one, we need to revisit the old traditions with less anachronistic images of trees in mind. Logan sprinkles his text with biblical quotes, especially from the Prophets (and of course Job) and helps us see horticulture front and center. He suggests trees were where humans encountered immortality - and in a way that leaves individualism behind. It'll be fun to revisit the trees of life, of the knowledge of good and evil, and others with copses and pollard knuckles in mind.

But there's another angle. Human beings have been able to make worlds with trees because of what Logan calls the "generosity" of trees; by this he mainly means the irrepressible resilience of sprouting. But trees have been doing their thing, together with their fungal and other symbionts, for a lot longer than we've been symbionts with them. And we're rather more symbiotic, not to say generous, creatures than modern imagination permits. Are their religious ideas which emerge from that deep shared history?

Another pic from in front of the Met: someone trimming an allée of linden, one blooming

Another pic from in front of the Met: someone trimming an allée of linden, one blooming

Friday, June 10, 2022

Job for trees

I've stumbled on a book which is messing with my sense of the history of humans and trees - in a good way! I mean, how could I not appreciate a book which picks up on a line in the Book of Job?

I've stumbled on a book which is messing with my sense of the history of humans and trees - in a good way! I mean, how could I not appreciate a book which picks up on a line in the Book of Job?

the way trees sprouted when cut gave people an intimation of immortality. When Isaiah envisioned the coming kingdom, he sang that no child would die or old person not live out their days; rather, each would have the life of a tree. Job too saw it plainly: in chapter 14, as he demanded that God tell him why He had broken him, he complained that death simply puts an end to men. He wished he might have been a plant: "For a tree there is hope, if it be cut down, that it will sprout again and that its tender shoots whill not cease. Even though its root grow old in the earth, and its stump die in the dust, yet at the first whiff of water, it may flourish again and put forth branches like a young plant." (25)

The central claim of the book, William Bryant Logan's Sprout Lands: Tending the Endless Gift of Trees (Norton, 2019) is that the way human beings lived with trees, from ten thousand years ago until two hundred years ago, was by cutting them to stumps to let them regrow. (pic) This process, known as "coppice," and supplemented by "pollarding," coppicing at at a point up the trunk of a tree above the reach of hungry animals, supplied the wide range of supplies of wood on which human socieities relied. A single stump can produce many shoots. Ttrees are in fact designed to keep sprouting, and a coppiced tree can in principle live forever, as its branches are always young.) Inspired, perhaps, by the rebounding of trees munched by megafauna and taken especially under wing by the emintently coppiceable hazel, early and later humans were by this method able to produce reliable crops of logs and poles of all strengths and girths as well as softer sprouts for fences and baskets and weirs - and nuts and fruit, too.

Since it took several years for trees to produce the desired sprouts, woodlands were subdivided into many areas coppiced at staggered times, making for dynamic and incredibly diverse ecosystems. Logan describes one such area (known as a fell or hagg or cant) which had been coppiced every 12-15 years since the 12th century - until the 1960s and now restored. Worth quoting from at length (87-90):

A fell was between half an acre and five acres in size. When first cut, it looked stone dead, littered with tumps. The shade-loving, four-eaved woodlant plant called herb Paris had bruned tips. A few sedges bravely tried to poke up their heads. ...

In the first three years following the cut, the sunlit dirt bloomed. At Queens Wood in London the gardeners counted 39 plant species in a hagg whe they coppiced it in 2009. Three years later, the same cre had added 156 more. Most of them had waited dormant for ht years sine the last cut. ... Most of the plants had done the same decade by decade for more than a thousand years. ...

In the fourth year after the cut, the young poles of the resprouting coppice began to shadow the ground. Life changed in their shade. The bramble and raspberry that had sprouted with the sun-loving flowers ... suddenly covdred every bit of open ground. By year's end, the meadowy landscape had become a thicket. All the other flowers had retreated to the edges or dropped their seed to wait for a change of days. No new species were added at this stage. Not a square inch of ground could be seen. Two more years passed, the poles growing taller and speading wider, the spiny shrubs rambling over everything beneath them.

By about the seventh year after the cut, the spreading tops of the coppice trees first closed the canopy. They quickly shaded out both raspberyy and branple. The two disappeared ebem ore quickly than they had come. Under this canopy, the ground opneed again and the shade dwellers emerged. Some fhese, like herb Paris and daffodils, wrre the same as had grown at first, but now they were joined by bluebells, dog mercury, wood anemones, ivy, and an occasional insistent bramble. ...

At Bradfield Wood there were only about seventy plant species in the closed coppice wood, a third of those that had grown in the sun. Under the regime of the closed canopy, these plants would grow on until the coppice was felled again, somewhere between the fifteenth and twentieth year.

Each coppice cant is a woodland history in miniature, repeated again and again as the cycle of cuting comes round. If there are fifteen cants in a given woods, though, it is only one scene in the performance. The art was to mix all of the stages in a way that could help the whole to thrive. The annual rhythm of cutting might move in a round, from one cant to the next in space. This brought beter light to the young panels, but it also helped the animals that preferred a given stage to stay with it.

In short,

A coppice wood is not a single being, but a synthetic ecosystem in which human participation is the key. Far more species of plants, insects, birds, and other creatures inhabit such a mixed landscape than would live in an untouched woodland. (86)

It's a marvelous vision of a recently lost way of living in temporal and spatial harmony - and interaction - with the natural world! It puts paid to modern images of trees with clean lines and single tall trunks, rising insouciantly above us, a vision of higher things or invitation to ponder them. Those are not the trees with whom human beings lived, shared, celebrated, cared. Those are not, in the terms Robin Wall Kimmerer (who blurbed the book) taught us, tree peoples. (I'm put in mind of the chapter in Braiding Sweetgrass which describes the harvesting of tree bark for basketry, and how the careful selection of - and thanks to - trees increases the flourishing of those species.)

Coppice may not have been quite as widespread as Logan implies (it doesn't seem to be the case, for instance, that the old Indo-European word for "tree" also means "cut," as he asserts, 10) but it's still nourishing food for thought. Controlled burns make sense as "fire coppice" (213), a stretch but arguably a really helpful one. It helps undo the pernicious idea of "wilderness" which bedevils our imagining healthy relationships with communities of plant peoples, and might point to some of the contingent causes; coppice was abandoned just as the Anthropocene got going in Europe. What will I do with it in "Religion of Trees"? We'll see... !

Pollareded beeches, Gorbea Natural Park, Basque Country, in Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees: Illustrated Edition, trans. Jane Billinghirst (Greystone Books, 2018), 30-31

Pollareded beeches, Gorbea Natural Park, Basque Country, in Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees: Illustrated Edition, trans. Jane Billinghirst (Greystone Books, 2018), 30-31

Thursday, June 09, 2022

Riotous

Wednesday, June 08, 2022

American art

One of the pleasures of summer is catching up on exhibitions. I was lucky to see the "Faith Ringgold: American People" show at the New Museum, a few days before it closed. And today I saw the largely overlooked exhibition "Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe" at the National Museum of the American Indian. Much of interest and beauty in both, even thangkas by Ringgold and abstractions by Howe!

One of the pleasures of summer is catching up on exhibitions. I was lucky to see the "Faith Ringgold: American People" show at the New Museum, a few days before it closed. And today I saw the largely overlooked exhibition "Dakota Modern: The Art of Oscar Howe" at the National Museum of the American Indian. Much of interest and beauty in both, even thangkas by Ringgold and abstractions by Howe!Tuesday, June 07, 2022

Illusions?

Monday, June 06, 2022

The forest for the trees

My principal interlocutor for these final paragraphs was a Poinciana (Delonix regia) in orange-red blossom, located by the banks of the Brisbane River at the end of Merthyr Road in New Farm, on Juggerah country. Despite the valuable assistance of the Poinciana, my comments in this section are not meant to refer to a particular tree. While I appreciate phytocriticism’s

My principal interlocutor for these final paragraphs was a Poinciana (Delonix regia) in orange-red blossom, located by the banks of the Brisbane River at the end of Merthyr Road in New Farm, on Juggerah country. Despite the valuable assistance of the Poinciana, my comments in this section are not meant to refer to a particular tree. While I appreciate phytocriticism’s  emphasis on individual plants and share Ryan’s related concern regarding ‘the marginalization of individual botanical lives’, I am also wary of how this emphasis might intersect with neoliberal constructions of individuality, and what it might therefore ignore about tree collectives and communal subjectivities, and their places in multispecies kinship networks. Even to talk about a generalised, individual tree ... may be a problematic atomisation of tree being: ‘individual’ trees may be more commonly interconnected through their root systems, so that the forests they compose, ... ‘are superorganisms with inter-connections much like ant colonies’ . In trees’ superorganismic collectivity, entwined by multimodal, chemically mediated forms of communication, it might be most useful to think of forest rather than tree expression.

emphasis on individual plants and share Ryan’s related concern regarding ‘the marginalization of individual botanical lives’, I am also wary of how this emphasis might intersect with neoliberal constructions of individuality, and what it might therefore ignore about tree collectives and communal subjectivities, and their places in multispecies kinship networks. Even to talk about a generalised, individual tree ... may be a problematic atomisation of tree being: ‘individual’ trees may be more commonly interconnected through their root systems, so that the forests they compose, ... ‘are superorganisms with inter-connections much like ant colonies’ . In trees’ superorganismic collectivity, entwined by multimodal, chemically mediated forms of communication, it might be most useful to think of forest rather than tree expression.Sunday, June 05, 2022

Saturday, June 04, 2022

Local history

We had a farewell dinner for one of our neighbors last night. After twenty-odd years in our complex, twelve on the floor on which we live, B is moving to be closer to family in Connecticut. J, the other guest, has lived in the apartment between B's and ours since 1965, and actually first moved to the complex when it was new in 1957! She showed us a book about the history of Manhattanville, which included this picture from the site where our complex stands - Fort Laight, at back right.

We had a farewell dinner for one of our neighbors last night. After twenty-odd years in our complex, twelve on the floor on which we live, B is moving to be closer to family in Connecticut. J, the other guest, has lived in the apartment between B's and ours since 1965, and actually first moved to the complex when it was new in 1957! She showed us a book about the history of Manhattanville, which included this picture from the site where our complex stands - Fort Laight, at back right.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)