Monday, October 31, 2022

Ask not for whom the bell tolls

Sunday, October 30, 2022

Dark is rising

Saturday, October 29, 2022

Friday, October 28, 2022

On our knees!

At dinner with friends, our frightening political moment came up by way of the deluge of messages we're all getting from candidates across the country just a few dollars from a target, fighting to keep their heads above water in the face of slipping poll numbers or dark money filling their opponents' coffers. One has to delete most of them, one friend said, but in order to do that you still have to process volleys of desperate cries for help - it doesn't help to know that they're all sent out by fund-raisers skilled in getting to us. (A fascinating Guardian article found that the messages for presumed Republicans and Democrats are dramatically different.) Another said they make him mad because they communicate a doomed sense of powerlessness - it's never enough, it never will be. An occasional donor but mostly a deleter, I realized the whole thing is abstract to me: all the money goes to ads I never see, leading a TV-less life.

Thursday, October 27, 2022

Antsy awareness

So we started with a guided meditation, the youngish Tibetan teacher Yongey Mingur Rinpoche inviting to a simple exercise in awareness of your body, then of your mind in your body, then of the area around you, and then expanding outward to the larger world - even beyond the clouds! - and back.

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

Symbiosis!

Tuesday, October 25, 2022

I say

The striking thing about the stories written by the students in "Religion and the Anthropocene" - stories many told me they'd struggled writing, as they had never been asked to write a story before, or worked primarily in dialogues, etc. - is how many were written in the first person.

In one a camp counselor tells of how their beloved camp, which not only they but their parents had gone to as children, has been changed beyond recognition by climate change. In another, a young woman tells of confronting a raging forest fire that may have been set by an ecoterrorist group of which her mother is a member. In another, a teenager from another planet writes a diary about a disillusioning trip to the Earth. In another, a protagonist tells us of her scheme to get into one of the forests where the billionnaires who haven't left the planet reside, only to be left outside the glass bubble with an electric vehicle with no more juice. In another, a drag queen in post-apocalyptic Los Angeles tells us how she follows her bouffant wig when it blows over the side of her paddle boat in a polluted current. In another, a young woman writes in her diary imagining the world her mother knew when she was her age. In another, a "raving scholar" describes their epiphany that anthropogenic problems can't be solved by the same sorts of anthropogenic interventions which caused them. In another, what will be the last polar bear describes their rage and confusion at human caprice and short-sightedness...

I asked the class this morning about this preference for the first person voice. Some (including a self-confessed diarist, who said she probably writes for her future self) said it was familiar and easier. Others told me it was common in contemporary literature, even if every narrator is an unreliable one! But the most interesting spoke of the challenges of the third person narrator, who needs to know everything that's going on: they couldn't pull that off.

One of the texts we read in preparation for this assignment was the section from Amitav Ghosh's The Great Derangement which arraigns the modern realist novel for concealing the realities of climate change in its focus on "individual moral adventure": to allow characters to grow and change believably, they need to be placed by the author in a believable place and setting - where believable means stabile, even unlikely turns of fate must be probable, or the writer will be dismissed as a failure. Ghosh, writing as himself a novelist, sees the problem as fundamental, structural. He discounts genres like science and speculative fiction as inadequate alternatives - nobody takes their world-building for real, he thinks, when the challenge of the Anthropocene is an uncanny reality - and recommends we revive premodern literary forms like epic, fable and myth. (In his Gun Island he does just that.)

But all the forms of storytelling Ghosh considers are delivered in the third person. Have my students found a way out of his dilemma, or just another way of avoiding facing it? In many of their stories, what's stable (relatively) is the voice of the narrator, as it tries, more or less successfully, to make sense of an increasingly confounding reality devolving around it. Perhaps John Green (crediting his wife Sarah) was right to quip that in the Anthropocene "there are no detached observers." Perhaps those who insist on the "thousand names of Gaia" are right to argue that the illusion of a single god's or god-like human's view of the planet has been punctured - and, for those who don't see that yet, needs to be punctured.

Still (I guess I'm one of those resisting puncture) the middle of my course, taking us from the "Anthropocene" section to "Religion," is a section called "Stories," and I was, with Ghosh, thinking of stories in the third person or at least the first person plural. Isn't that what's implied when, for instance, Haraway writes in her "Camille Stories" that the communities where a new way of being emerged discovered that "storytelling was the most powerful practice for comforting, inspiring, remembering, warning, nurturing compassion, mourning, and becoming-with each other in their differences, hopes, and terrors"? Maybe not! Maybe, in the year Annie Ernaux won the Nobel Prize for Literature, the stories that keep things real are all in the first person singular ... but addressed to other first persons, too.

And yet the reading for today's class was Jill Schneiderman's "Awake in the Anthropocene," a celebration of the contributions geological and Buddhist ways of seeing beyond the personal can make to Anthropocene challenges...

Monday, October 24, 2022

Unwanted future

Sunday, October 23, 2022

Church of the tree

Saturday, October 22, 2022

Friday, October 21, 2022

Centrifugal Trinity

Among the many splendiferous objects in the Met's blockbuster exhibition on the art of the Tudors is an enormous 15th century tapestry, the only survivor of a set of ten stretching 300 feet, showing the Trinity creating the world. Over six days of creation and the seventh of rest, that makes twenty-one identical scepter bearing figures, doing their thing, and quite upstaging the celestial and terrestrial objects they're calling into existence! Here's Gen 1:11-12:

And God said "Let the earth put forth vegetation: plants yielding seed, and fruit trees of every kind on earth that bear fruit with the seed in it." And it was so. The earth brought forth vegetation: plants yielding seed of every kind, and trees of every kind bearing fruit with the seed in it. And God saw that it was good. (NRSV)

And God said "Let the earth put forth vegetation: plants yielding seed, and fruit trees of every kind on earth that bear fruit with the seed in it." And it was so. The earth brought forth vegetation: plants yielding seed of every kind, and trees of every kind bearing fruit with the seed in it. And God saw that it was good. (NRSV)

The tapestry's sun and moon and plants and fish and animals are lovely but tiny compared to these engaging triads, each in a different moment of almost ludic divine sociality; only the humans created in their image are big enough to catch the viewer's eye. 'Tis a sight behold, and towers suitably over (it's 14 feet high) an exhibition whose narrative tells of the divinization of an upstart royal line.

There are too many other splendors to mention, but other tapestries remind us of royals as destroyers as well as creators. Henry VIII apparently specially commissioned this scene of St. Paul directing the burning of heathen books, billowing smoke meticulously woven.

There are too many other splendors to mention, but other tapestries remind us of royals as destroyers as well as creators. Henry VIII apparently specially commissioned this scene of St. Paul directing the burning of heathen books, billowing smoke meticulously woven.

Recycled

Thursday, October 20, 2022

Untimely

In "Religion and the Anthropocene" this morning, students shared stories they had written. You might recall that writing an "Anthropocene story" was part of the "Anthropocene humanities" course I taught at Lang and twice for the Renmin summer school, and I knew it would be a revelatory experience for these students too. I had the class break up into threes, so each could present their story to an intimate audience, as well as hear two other stories. Then students were asked to tell the rest of the class about the stories they had heard (not the ones they had themselves written). With as vague a prompt as I had given, the stories ranged widely in theme and voice, amazing and delighting us one by one but even more cumulatively.

Each little clutch of students was its own mutual appreciation society, and hearing the students praise each other's work drew out affinities between their animating concerns.

One group included a story about extraterrestrial entities coming at some point in the future to visit the Earth, a planet whose beauty they had heard about from their parents, only to find it a devastated wasteland. Another story in that group was the imagined diary entry, from a nearer future, of someone who might be the author's future child, noting sadly that the world they'd heard about from their mother was so different from the one they knew. Strange synchronicity in solastalgia, the sense that the world we know and love will not be there in the future! The group's third student (whose story was entirely different, a John Green-inspired vignette on green fashion at a skate & surf shop) brought it home to the present, asserting boldly that anyone in her generation would give almost anything to be able to experience even a day from the world in which our parents grew up.

This remark had me imagining the world in which my parents grew up, with its midcentury modern aesthetics and trim black and white photos, before I realized, with a start, that she was talking about the one I grew up in. (Indeed, I may well be older than her parents.) Woozy time vertigo ensued, and persists. The class's other stories, in their various ways, have a similar sense of a world irrevecably slipping away, indeed already part way gone.

Wednesday, October 19, 2022

Tuesday, October 18, 2022

Monday, October 17, 2022

Importunate

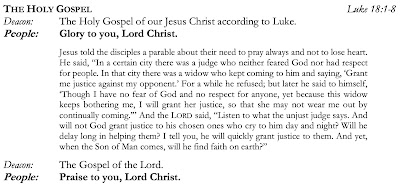

Yesterday's Gospel reading, known as the "parable of the unjust judge" or "parable of the importuante widow," was one of the parables which come up in Octavia Butler's Parable of the Sower. Our rector, who was preaching, was the person who directed me to Butler's book a few years ago - and led a group of parishioners in a discussion of the book as part of the recent "Summer Reads."

Yesterday's Gospel reading, known as the "parable of the unjust judge" or "parable of the importuante widow," was one of the parables which come up in Octavia Butler's Parable of the Sower. Our rector, who was preaching, was the person who directed me to Butler's book a few years ago - and led a group of parishioners in a discussion of the book as part of the recent "Summer Reads."

The story was fresh in my mind because our first class on the book in "Religion and the Anthropocene" focused on parables, including this one. They're often more complex and more charged than they at first seem. A story which, as one student said, "casts shade on God" (why an unjust rather than just a busy judge?), Luke 18:1-8 is the text Parable of the Sower protagonist Lauren Olamina chooses to preach on when her father has gone missing and is presumed dead. Its story of wresting justice from an unjust judge prefigures Earthseed, the new religion Olamina will channel into being, a religion where "God is change" and where we are called to "shape God."

But the rector didn't mention it. She focused instead on the importance of persistence and the virtue of boldness. (The day's Old Testament reading was Jacob wrestling with the angel and not letting the mysterious being go until he blessed him, so it made sense, though it jibes with Earthseed too.) I asked her about it afterwards. The connection had completely slipped her mind, she said. But, we realized, Earthseed hadn't. Her sermon ended with ringing words about the importance of making bold claims - and how making them changes us. Olamina would approve:

All that you touch

You Change.

All that you Change

Changes you

Sunday, October 16, 2022

Saturday, October 15, 2022

Friday, October 14, 2022

Against the grain

Thursday, October 13, 2022

Translucent obsessions

Wednesday, October 12, 2022

Ficus religiosus

Shanahan also stresses that, while not all figs are stranglers, many start their life high up in another tree which they ultimately encircle and overwhelm. (He illustrated his own book; iage at right is on page 10.) Some of these host trees survive but many die, rotting away to leave hollows at the heart of the fig's growing network of trunks and secondary trunks. (This was what one ecologist remembered climbing in at that panel I attended a few weeks ago.) For my students, this punctured the idea that trees are peaceful beneficent beings.

Shanahan also stresses that, while not all figs are stranglers, many start their life high up in another tree which they ultimately encircle and overwhelm. (He illustrated his own book; iage at right is on page 10.) Some of these host trees survive but many die, rotting away to leave hollows at the heart of the fig's growing network of trunks and secondary trunks. (This was what one ecologist remembered climbing in at that panel I attended a few weeks ago.) For my students, this punctured the idea that trees are peaceful beneficent beings.Disarmed

Monday, October 10, 2022

Religious arboretum

Saturday, October 08, 2022

Friday, October 07, 2022

Wednesday, October 05, 2022

Courtyard maple darsan

Monday, October 03, 2022

Leaf peeper's nausée

Although we were constantly applauding, nobody was putting on a show for us. The pigments that gave us colors we deliriously grasped for names for (claret? pink grapefruit? rhubarb? blood?) had served some other purpose once. At that chlorphyl-filled time, the leaves were green because they absorbed reds and yellows. Titillating the likes of us by bouncing the golds and scarlets back at us was never the point! By the time the trees elicit gasps from tree peepers like us, the leaves' work is done - except decomposing on the forest floor. It was like showing up for the curtain call of a theatrical performance, or indeed at the stage door,

Although we were constantly applauding, nobody was putting on a show for us. The pigments that gave us colors we deliriously grasped for names for (claret? pink grapefruit? rhubarb? blood?) had served some other purpose once. At that chlorphyl-filled time, the leaves were green because they absorbed reds and yellows. Titillating the likes of us by bouncing the golds and scarlets back at us was never the point! By the time the trees elicit gasps from tree peepers like us, the leaves' work is done - except decomposing on the forest floor. It was like showing up for the curtain call of a theatrical performance, or indeed at the stage door,  sharing, but seeking to see them twice! Spectres of spectres! Isn't there something morbid about the whole thing? I took comfort in knowing that we visit in all seasons we can, noting the kaleidoscopic ensemble of the forest from floor to canopy. (Indeed, the floor is the roof of a deeper world, peeping out through the wild variety of mushroom fruiting bodies.) Still, I had to confess a particular rapture produced by the flaring colors of the fall - I'm one of those people who say "fall is my favorite season." Why not spring? Or summer, which I tend to dismiss as dull. Leaf peeper's delight is not about but despite the trees, yet it's real.

sharing, but seeking to see them twice! Spectres of spectres! Isn't there something morbid about the whole thing? I took comfort in knowing that we visit in all seasons we can, noting the kaleidoscopic ensemble of the forest from floor to canopy. (Indeed, the floor is the roof of a deeper world, peeping out through the wild variety of mushroom fruiting bodies.) Still, I had to confess a particular rapture produced by the flaring colors of the fall - I'm one of those people who say "fall is my favorite season." Why not spring? Or summer, which I tend to dismiss as dull. Leaf peeper's delight is not about but despite the trees, yet it's real.Sunday, October 02, 2022

Adirondack idyll

We snuck away north to the Adirondacks for a long weekend, just as fall was starting to fall there! The fringes of the savage hurricane churning to the south peeked over the horizon (above), but our skies were clear, by night as well as day.

.jpeg)