What a difference six days make!

Thursday, May 15, 2025

Wednesday, May 14, 2025

Tuesday, May 13, 2025

Monday, May 12, 2025

Rippled

In "Religion and Ecology" we read an essay by John Daido Loori about Dogen's "Mountins and Waters Sutra," but what really got to students was a scratchy old film he'd shot, called "Water speaking water." (There are longer versions.) It was made among the streams flowing into Raquette Lake, near one of whose shores we are staying. Here's the lake sharing late in the day enlightenment. There are mountains hidden in water!

In "Religion and Ecology" we read an essay by John Daido Loori about Dogen's "Mountins and Waters Sutra," but what really got to students was a scratchy old film he'd shot, called "Water speaking water." (There are longer versions.) It was made among the streams flowing into Raquette Lake, near one of whose shores we are staying. Here's the lake sharing late in the day enlightenment. There are mountains hidden in water!

Sunday, May 11, 2025

Overstory

Saturday, May 10, 2025

Friday, May 09, 2025

Back in the Dacks

All three of my classes wrapped up this week - rather sweetly, too, if you ask me. Papers need to be read and grades tabulated before graduation next week, but all that can be done anywhere. So we hopped in the car and are back in our beloved Adirondacks.

I could devise a meaningful-seeming segue if you wish: the Friday class was the one on William James' Varieties, and a nearly mystical experience in the Adirondacks seems to have been decisive in that work's composition. Call it research! And of course, it's the perfect segue back to my own religion of trees work, too.

We decamped to the 'Dacks around this time last year, too, but this is a week and a half earlier - even deeper back in the spring which, in New York City, is already passign the baton to summer. We've been here in early May before, but didn't notice these gaggles of ferns popping up along the rain-flush Hudson before!

Wednesday, May 07, 2025

Tree tale

It's a gorgeous sunny day, and the Lang courtyard maples' leaves are already almost full size and deepening green in taking best advantage of it.

It's a gorgeous sunny day, and the Lang courtyard maples' leaves are already almost full size and deepening green in taking best advantage of it.

But perhaps you've been wondering what's become of that red maple branch which came so close to my office window this spring, and allowed me rapturous witness to the magical procession from bud to flower to growing samara to leaf. It's a little complicated. The short version is that the branch is broken.

Not completely, but it dangles down now rather than reaching up. Here's how it looked last week; below is the way it's looking

now.

Not completely, but it dangles down now rather than reaching up. Here's how it looked last week; below is the way it's looking

now.

I

can't remember a branch so close before. I even encouraged students to

reach out the window and touch it! But the very thing that made it available for my devotion put it at risk. When the wind eddies in the courtyard, branches brush against the windows. No surprise that some will have snapped from the collision.

Tuesday, May 06, 2025

Greening of the self

Sunday, May 04, 2025

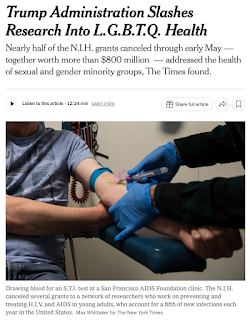

DEI? No: DIE

How do you say "we don't care if you live or die"? There are so many ways. Here as elsewhere there are so many undercurrents in this administration that are homicidal .

Democracy is supposed to be about sharing a society with others, maybe even delighting in the privilege of the shared journey. Not these guys.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)