Wednesday, March 31, 2021

World Christianities

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

Monday, March 29, 2021

Pronouns of God

This morning I stumbled on wonderful words from the brilliant womanist biblical scholar Will Gafney (whom we met in the Scholar Strike), part of a recent panel on "Rainbow Theology: Intersections of Race, Gender, and Sexuality." Her focus was pronouns, and what a difference they make to theology, and to liturgy. Gafney began:

Human beings contain multitudes, multiverses, like our Creator. That she, he, they, One who is three, seven, twelve, many is ultimately inarticulable yet mysteriously, in some way reproducible. The earthling created from the earth, the human created from the humus, was soil and spirit and bone and blood. And it, they/them was gender-full and in that gender-fullness was the image and likeness of God.

There is an incantatory loveliness to this she, he, they, One who is three, seven, twelve, many. It feels like praise, joyful praise. I'll try using it. Simple pronouns, or even the careful but abstract gender-less language of "God" and "Godself," don't communicate the fullness of the creator, or the creation.

There is an incantatory loveliness to this she, he, they, One who is three, seven, twelve, many. It feels like praise, joyful praise. I'll try using it. Simple pronouns, or even the careful but abstract gender-less language of "God" and "Godself," don't communicate the fullness of the creator, or the creation.

I use the example of our language because I have made the argument as a woman that you tell me what you think about me by how you talk about God in whose image I am created. If your language about God does not include my creation, that tells me that you do not see God when you see me and you do not see me in God. This is also true for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and asexual people. If your entire theological and linguistic framework is binary, then there is no room for the fullness of God’s creative artistry with the human palette.

The first tree flowering in Washington Square Park joins me: Amen!

Sunday, March 28, 2021

Saturday, March 27, 2021

Friday, March 26, 2021

The problem of good in the Anthropocene

I'm not sure critique of the hubris of the "Anthropocenologists" (Bonneuil and Fressoz's term) is qualitatively different from arguments which have been made for many years now about the ecological dangers of certain kinds of monotheism, and of the patriarchal colonialist capitalist forms of thought with which it was allied in recent centuries and which perpetuate its dangers. What is new - that some of our shameless shenanigans might be leaving a trace discernible by future geologists - isn't obviously important, when (some) humans have been devastating human and other-than-human worlds for half a millennium. Indeed, the supposed novelty of the Anthropocene can serve as a distraction from longer term ecological problems folks have been thinking and organizing about for decades. From this perspective the arrival of "Anthropocene" discourse is an unwelcome reaffirmation of human exceptionalism (the Man!) just as the extent of colonial damage and the delicacy of our entanglement with other species are coming into focus.

Beyond understanding and redressing the forms and structures of devastation (some) humans have wreaked, I find promise in the effort to articulate the "Anthropocene" change in (some, my) people's sense of the harmonizability of human plans with earth and its systems and communities. Isabelle Stengers describes as the "intrusion of Gaia" the experience of a planet no longer content to let (some) humans instrumentalize and exploit it, a world which hurts us back. The experience of the Anthropocene isn't near-invisible layers of geological residue in the future but a widening gyre of devastation from fire and flood and storm right now. This is not the Anthropocenologists' safely sublime experience of newly discovered power - who knew we could be so baaad! - but one of what seems a new difficulty and resistance, frustration and confusion. Bronislaw Szerszynski has suggested that these experiences are giving rise to new "gods" and "spirits," as the no longer safely secular background of the natural world becomes feisty foreground - powers which demand devotion and sacrifice. But Stengers' Gaia can't be placated. The world may seem newly unruly because of what (some) humans have done, but it's not interested in repairing its relationship with us. At at that conference in Indiana three years ago I tried linking this sense of a nature grandly but disconcertingly oblivious to our concerns to the theophany of Job - other scholars had too - but it didn't take. That ancient text may somehow recall an earlier time when human beings were less confident of their place at the table of the world. The Holocene was in fact a lot less stable than it seems to us now in retrospect to have been! But the pertinence of any ancient text now seems open to question. I'll keep bringing Anthropocene questions to Job but only because I'm already working with Job; I don't want to be arguing that this is a text folks not already so oriented should turn to. Its intrusion of Gaia is contained within a relationship, however sublime (a command performance is hardly an intrusion!), with an ordering care that addresses us by name, and, more troublingly, the story is very much one of a solitary human master of the universe experiencing a (passing) crisis of privilege. The former seems important to work through, within a Christian theological framework, but the latter is a formidable problem in this time of clarity. And I realize neither is what I want to bring to the broader Anthropocene and religion discussion. (Even in Indiana I was really rewriting the book to make it less anthropocentric, its form less cyclical.)

At at that conference in Indiana three years ago I tried linking this sense of a nature grandly but disconcertingly oblivious to our concerns to the theophany of Job - other scholars had too - but it didn't take. That ancient text may somehow recall an earlier time when human beings were less confident of their place at the table of the world. The Holocene was in fact a lot less stable than it seems to us now in retrospect to have been! But the pertinence of any ancient text now seems open to question. I'll keep bringing Anthropocene questions to Job but only because I'm already working with Job; I don't want to be arguing that this is a text folks not already so oriented should turn to. Its intrusion of Gaia is contained within a relationship, however sublime (a command performance is hardly an intrusion!), with an ordering care that addresses us by name, and, more troublingly, the story is very much one of a solitary human master of the universe experiencing a (passing) crisis of privilege. The former seems important to work through, within a Christian theological framework, but the latter is a formidable problem in this time of clarity. And I realize neither is what I want to bring to the broader Anthropocene and religion discussion. (Even in Indiana I was really rewriting the book to make it less anthropocentric, its form less cyclical.)

But a few days ago I had an idea for a contribution I might be the one to make, a possibility at least. It would connect to arguments I made way back when about the problem of evil - and the problem of good. The main argument then was that until modern times the problems of good and evil were engaged together. The most profound responses, to me at least, linked them - evil was understood as the privation or destruction of good, whose vulnerability was as heartbreaking as its existence was gratuitous. What happened to make the problem of evil so eclipse the problem of good that we don't even hear about the latter anymore was, in part, that the world came to be experienced as stable, habitable, controllable. Order became a background we could take for granted, not a precious or precarious gift, and it was the disruption of order, always the more urgent "problem," that came to monopolize attention. Thus could a Schopenhauer turn the old argument that philosophy begins in wonder on its head and say it had always been wonder at evil that was the source of thought. Modern thought has indeed been fed by and feeds the problem of evil, but I argued that reflection on evil without good was ultimately a hollow thing, undermining the claim of the good as well as our understanding of its nature. (That there is a good - not just varied and competing fancies about ultimately valueless reality - seems to me one of the unnoticed implications of the certainty that there is a universally acknowledged problem of evil.)

Here's the new idea. What if Stengers' "intrusion of Gaia" marks the wobbling end of that confidence in a natural order we felt we could take for granted? Objectively speaking, the Anthropocene centuries (and millennia) ahead will be less stable than the centuries (and millennia) of the Holocene which cradled the development of human civilizations. But until the era when modern science, technology, and fossil fueled fantasies of transcending biological cycles made it feel stable, the Holocene world order, too, felt precarious. Widespread belief that the world order was breaking down may now look to us like part of a deep confidence in cycles of death and rebirth - a confidence no longer warranted! - but they report experience of failing rather than resilient order. As even Job knew, hope has always been hope against hope. It's not clear that all fruits of Holocene culture are rendered obsolete by the Anthropocene, when not indeed complicit in it. The damage wrought by the Anthropocene is vast but recent. Popular and scholarly attention is drawn by "indigenous" traditions thought to have a better grasp of how to live with our non-human kin in a disrupted world, but as Frédérique Appfel-Marglin's "reverse anthropology" reminds us, most people in history - and even today - lived outside the deadly imaginings that drive the Anthropocene. There are many, not few, resources for living on a "damaged planet" if we look beyond colonial capitalist western modernity.

Arguing about periodization isn't a game I want to play. But I'm sensing it might be an intriguing way to dislodge the sense of Anthropocene doom to restore the complementarity of the problems of evil and good. I'd have to venture a historical story, as I sketch above, but what would make it interesting is the resonance the problem of good might now again have. My main work would be evoking how good was conceived and experienced before it became background noise - precious and precarious and mysterious - and then bringing this into conversation with contemporary fumblings with ontology and recoveries of wonder. Gaia will remain implacable, but perhaps we can find better ways to find and sustain refuges from the deceptive claims and compromises of Anthropocenology.Construction

Thursday, March 25, 2021

Sanctuary

Before my volunteering stint at Holy Apostles today I lit a candle for a friend who is gravely ill. This is a space he has known and loved both as church and soup kitchen, communities for feeding body and soul.

Wednesday, March 24, 2021

Bad theology, and good

Two pieces of powerful public theology crossed my path today, addressing painful current events. In one, Mihee Kim-Kort, a Korean American Presbyterian minister, calls out the bad theology which, going hand in hand with patterns of anti-Asian prejudice in the U. S., led to the horrific attacks in Atlanta last week. She recounts growing up within a Christianity which could not imagine a woman preaching.

Kim-Kort contrasts this with the inhuman Evangelical "purity culture" which shaped the Atlanta killer, unable to see others as anything but threats - especially Asian women, already denied full reality as Americans by entrenched stereotypes. Reports that the killer had a "strong Christian faith" gave me chills. The stronger Christian faith Kim-Kort describes gives me hope.

The other piece is by James Alison, long a hero, a pathbreaking gay Catholic theologian who manages to rise above rancor at churchly homophobia to prophetic love. In his newest piece he's responding to the recent Vatican announcement that forbade priestly blessing of same-sex unions (not to mention marriage). Alison's response is to describe the announcement as a "tantrum," and to recommend readers not take it personally. The writers are like people who've locked themselves in a small room, a conception of "objective truth" which does not do justice to the reality of God's creation. Their conniptions represent "self-fueling delusion at work." If only they could leave their little room, they'd see a world full of things to bless.

And this is their sadness: our brethren (sic) are locked into an account of objectivity which bears passing little relationship to the reality of creation as we are coming to know it and participate in it. ... Where frightened morality tries to close things down, wisdom, starting from our rejects, opens up the reality of what is, as we undergo being forgiven for our narrow goodness and hard-heartedness, sifting through our fears and delusions. And so we discover our neighbours as ourselves, and how we are loved. ... And so to the matter of blessings given to, received and shared by, same-sex couples: Our Lord teaches us to know a tree by its fruit. He provokes our learning process. And it leads us to find things to bless, forms of blessedness old and new. The power and the glory of the Creator do tend to show themselves through our becoming, as we discern what we are for and who we are. It is a learning which is especially blessed when we find ourselves being forgiven for having categorised groups of people in false ways, and discovering that life is richer and better for all of us when they are encouraged to be who they are.

How different are theologies which exclude and attack the new and the other from those which are able to see in all the work of God, who feel the grace-filled momentum of discovering the divine in more and more of human life! Both Kim-Kort and Alison help us see that a liberating theology, one which liberates us to love the world and all in it, must begin at home with acceptance that none of us is a mistake.

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

Undercover

Transcription miss (or hit!) of the month: when I spoke of "SBNR" (spiritual but not religious) in my prerecorded lecture, the automatically generated transcript had me opining on espionage!

Monday, March 22, 2021

On the prowl

This is, apparently, a panther as imagined in 11th century France, and the pretty curls are the sweet-smelling breath with which it attracts prey. It resides now at The Cloisters (a coda to our trip, en route to returning the rental car), where one can feel an illusion of safety from the panthers of our time.

This is, apparently, a panther as imagined in 11th century France, and the pretty curls are the sweet-smelling breath with which it attracts prey. It resides now at The Cloisters (a coda to our trip, en route to returning the rental car), where one can feel an illusion of safety from the panthers of our time.

Sunday, March 21, 2021

Saturday, March 20, 2021

Wednesday, March 17, 2021

Tuesday, March 16, 2021

Back in the Dacks

In what's becoming something of a tradition for us, we're spending Spring Break revisiting winter. We're back at the cosy Airbnb place where we spent a week three months ago, grateful to have traditions, however quixotic, and to have the chance to keep them going.

In what's becoming something of a tradition for us, we're spending Spring Break revisiting winter. We're back at the cosy Airbnb place where we spent a week three months ago, grateful to have traditions, however quixotic, and to have the chance to keep them going.

Monday, March 15, 2021

Inside and out

Saturday, March 13, 2021

Friday, March 12, 2021

Home to roost?

Another animal lesson from John Thatamanil, questioning a common view of the difference between religious studies and theology:

Comparison is understood to belong to the descriptive labor of religious studies whereas the normative work of constructive theology is expected to operate from resources drawn from within the boundaries of a single tradition alone. Such boundedness is even taken to be the hallmark of theology: philosophy of religion can be universal, but theology must be confessional and particular. The philosopher of religion is the free-range chicken who can wander about and eat what she wants; the theologian, by contrast, must live and eat within the coop of tradition. (22)

Thatamanil is contesting this distinction from the theology side, arguing not only that comparative theology is a legitimate enterprise but that it should be part of constructive theology. (A "theology of religious diversity" is required too.) For the first centuries and the most recent, at least, Christian theologians had no choice but to articulate their faith in language shared with - even originating with - other traditions. Constructive theology was comparative theology, and should be again. Religious diversity, too treated as an irrelevance or a threat by Christian theologians, is in fact the most fruitful context for theologizing: it is not a problem but a promise.

I'm more used to seeing the distinction made from the religious studies side, but it's refreshing to see how it looks from theology. Thatamanil is fully conversant with the critiques religious studies has been making of its terms, challenging the notion of religions as "monolithic, impermeable, tightly systematic, and unitary wholes" (43) and critical of those who want their traditions to be that way. But acknowledging that traditions have been internally mixed and mutually mingling throughout history doesn't make comparison moot: it takes us back to the constructive, normative work which builds and sustains all traditions, a work which thrives in diversity.

Actually religious studies has been refusing this reality for a while, too. Winnifred Fallers Sullivan appears in my classes to expose the impossibility of religious neutrality (in scholarship or law), to recognize that, whether we admit it or not, whenever we opine about religion we are doing theology of one kind or another. But it's harder for a free-range chicken to admit that coops are good for chickens. Sullivan glosses "speaking theologically" as "speaking directly of the existential realities that we all face," but compared to the overlapping worlds of study and practice and dialogue which Thatamanil describes, that seems pretty slim pickings.

John J. Thatamanil, Circling the Elephant: A Comparative Theology of Religious Diversity (New York: Fordham University Press, 2020)

Thursday, March 11, 2021

Covid 365

The newspapers are full of reflections on the year that covid knocked us off our feet - March 11th was the day WHO officially declared the world was in pandemic - and reports from when "people knew" that something bad was starting. On March 11th last year, I had my last in-person class, although I'd told the students to stay home (I had a visitor who was willing to talk to an empty room). We'd learned the day before that our classes after Spring break would be online for at least a few weeks. It was still a few days before the last in-person service at Holy Apostles. My last trip to school was still six days away. And yet already on March 11th last year I had intimations, and some crocuses in Washington Square Park, which in any other year would have delighted me, instead made me think of coronaviruses...

According to the Johns Hopkins site, 2,628,363 souls have been lost to covid, 530,624 of them in the United States. May they Rest In Peace.Wednesday, March 10, 2021

The room in the elephant

If I were a cartoonist, I might try to draw a group of blindfolded people in a room, each facing a different direction. One is fingering a column supporting the ceiling, another the rope of a curtain, a third a velvet wallpapered wall. Or perhaps it's in an exotic ancient place where one is touching a palm leaf fan, another a tree trunk, a third a spear. The joke in either case would be that all the people are saying "it's an elephant!"

The joke would work, if it did, because people seeing the cartoon would immediately call to mind the famous story of the blind men and the elephant. In that fable, they're all standing around an elephant, fingering an ear or a leg, the side or the trunk, a tusk or the tail. "A fan!" says one. "No, a tree!" "A wall!" "A snake!" "A spear!" "A rope!"

This story, of ancient Indian provenance (some attribute it to the Buddha) but told in many places, makes fun of the limits of human knowledge. In the religious world it's often told as a way of making sense of the apparent differences between religious traditions, a call to mutual respect - and humility. "Ultimate reality" (say) is like the elephant, and the religions are like these blind men, getting some small part of reality right but ultimately getting even it wrong by taking it for the whole. We laugh, but the laugh's on us - all of us.

There are problems with this allegory, of course. If it's not the omniscient Buddha, how does the storyteller know it's an elephant we're talking about? Isn't the point of the story that, with respect to ultimate reality (say), we're all like the blind men, leaping to unwarranted conclusions? And if the storyteller can know, then why tarry with anyone else's view, incomplete as she's shown them to be? Critics of religion like Russell McCutcheon see the story as an ultimately incoherent attempt to assert that there's a there there, that all religions are after the same thing - in fact a thing we think we basically know after all, for all protestations of false modesty. I suppose my imaginary cartoon would make a similar point: the one thing that's not there is an elephant, though everyone thinks there is! (But still, why trust the cartoonist's claims to omniscience...?)

My Union neighbor John J. Thatamanil's new book Circling the Elephant: A Comparative Theology of Religious Diversity tries to vindicate the story's power, for all its problems. He readily acknowledges the problem of the storyteller who claims to know it's an elephant we're dealing with. Indeed, tapping years of experience in Hindu-Buddhist-Christian dialogue, he teases out several other problematic assumptions baked in the way the story's usually told, too: the elephant doesn't speak (but many religions are based on revelation), each blindfolded person is alone (but every tradition is a polydoxy of multiple views), and we assume that people and the elephant are separate (when non-duality is important for many schools of insight): Only the flattest forms of theism, which take ultimate reality to stand in discrete and spatial transcendence to the world and humanity, conform to the pictorial logic of this allegory (11).Too many tellers of this tale also miss the fact that each of the men gets something right, something the others don't know (though it may take dialogue with otherto show each of us what the true is in our own views) Thatamanil prefaces his account with the objections of John M. Hull, a Christian theologian who lost his sight in middle age, who says that jumping to conclusions "is precisely what the blind do not and cannot afford to do." This is a story anchored in the confidence of the sighted but perhaps it can be retold, making the difference between visual and tactile knowing a feature, not a bug. Tactile knowing, Thatamanil paraphrases Hull, is incremental, patient, and must proceed deliberately. Vision gives the impression of being synchronic; touch is perforce diachronic. (5)

Thatamanil's own way of turning the story to good use is diachronic, too, breaking it free from a static insight. The way one might discern that one was groping to understand the same thing as others - not unrelated and unconnected things, as in my imagined cartoon - would be to talk to these others, to move to their position, to try to touch what they touch. If you "circled the elephant" you might even confirm that you were all trying to make sense of the same thing(s) after all, regardless what the wannabe omniscient narrator claims. These ideas recover the inspiration of the story, I think, making its very shortcomings reasons for engaging more wholeheartedly in the "holy work" of interreligious exploration.

Even if there's no elephant in the room!

Tuesday, March 09, 2021

Suspended in the great sphere of the sky

Had one of those convergence/synchronicity moments today. I was reading a 2006 article by British anthropologist Tim Ingold, referenced in Pantheologies, called "Rethinking the Animate, Re-Animating Thought." Ingold defends what he calls the "animic perspective" against the views of western anthropologists as well as scientists. This condition of being alive to the world experiences the world as one of continuous birth (a phrase from a Wemindji Cree hunter), all of us helping form a meshwork as we go our various ways, something which western thought fundamentally misconstrues as an "environment" outside us.

Importantly, all of us includes not just people and animals and plants but celestial forces, too, sun and moon and especially wind and thunder.

In the animic ontology, what is unthinkable is the very idea that life is played out upon the inanimate surface of a ready-made world. Since living beings … make their way through a nascent world rather than across its pre-formed surface, the properties of the medium through which they move are all-important. That is why the inhabited world is constituted in the first place by the aerial flux of weather rather than by the grounded fixities of landscape.

Our actual living is concealed from us by imagining the earth beneath our feet as solid but inanimate material and the air above as inanimately immaterial, with us, part material and part immaterial but somehow other to both, in but not of the world. We could learn from animists to notice everything interacting in its pathways, and how at every moment to respond to the flux of the world with care, judgement and sensitivity.

Good stuff! But then he wrote

In this world the earth, far from providing a solid foundation for existence, appears to float like a fragile and ephemeral raft, woven from the strands of terrestrial life, and suspended in the great sphere of the sky.

and I was flying, I was reminded both of my favorite line from G. K. Chesterton's book on Francis of Assisi (whom Lynn White thinks the closest thing to a Christian animist), how he has a vision of Assisi as if suspended in air... And my favorite line from Willa Cather's Death comes for the Archbishop, describing the wondrous sky of New Mexico: Elsewhere the sky is the roof of the world; but here the earth was the floor of the sky. Suspended indeed!

And then Ingold went on

far from facing each other on either side of an impenetrable division between the real and the immaterial, earth and sky are inextricably linked within one indivisible field, integrated along the tangled life-lines of its inhabitants. Painters know this. They know that to paint what is conventionally called a ‘landscape’ is to paint both earth and sky, and that earth and sky blend in the perception of a world undergoing continuous birth.

Painters! Ingold paraphrases Merleau-Ponty's praise of Cézanne's painting - His vision is not of things in a world, but of things becoming things, and of the world becoming a world - and quotes Klee too. But I was of course thinking of Monet, and that poem of Lisel Mueller's, which I discovered, entirely unrelated, just two days ago:

"Rethinking the Animate, Re-Animating Thought," Ethnos 71:1 (March 2006): 9–20

Monday, March 08, 2021

Pantheistic pluralisms

So I said a fantastic book I'd started reading, called Pantheologies: Gods, Worlds, Monsters, seemed like the kind to change your life. Well, after taking a big intoxicating swig each day for a week, I've finished it! Has my life changed?

First I need to say that it made me green with envy. Such sweep, such brilliant interweaving, such wit! And it brought together many things I've been interested in, thinking thoughts to their conclusion which I hadn't gotten around to - or dared to. It has William James on pluralism at the beginning, Lynn Margulis and Donna Haraway and Deborah Bird Rose in the middle, and Octavia Butler on "God is Change" at the end, and these aren't even the main figures discussed, which include Spinoza, Bruno and Einstein! It also integrates insights from feminist, queer, post-colonial, anti-racist and new animist literatures - and Christian theology, too. Stitching it all together are a series of delightful cameos by the polymorphous figure of Pan. A friend tells me this book represents to him what philosophy of religion, which many have written off as dead, should be. My thought was that this sort of work was what the Gifford Lectures were designed for, showing the affinities and synergies of science and religion in a new key. It's a reminder, too, of how exciting work in the history of ideas can be.

The larger project of the book is to make pantheism - the identification of the universe and divinity (a term Rubenstein favors over God) - thinkable. This is startlingly hard to do as, she shows, much of western thought has been premised on its unthinkability. Certainly, a particular version of pantheism - with James she calls it "monistic pantheism" - is thinkable, if almost always only in caricaturing the perceived dangers of others' ideas, but it's not what she's after. "Pluralistic pantheism" focuses on the immanence of divinity in the universe, rather than positing any sort of unity, and it's wild. In her careful readings of Spinoza, Einstein and even James, she finds thinkers whose thought was pointing toward such a pluralistic pantheism who were ultimately unwilling to complete the thought, falling back into some sort of monism or, worse still, what she dubs "mantheism": God is immanent, not in the material universe, but rather in one (allegedly) exclusive conscious corner of it (37).

Perhaps these thinkers are blinkered by the limits of western imagination - at least since the later Stoics shut down their pluralistic pantheism and Christians followed. Rubenstein introduces the "new animist" idea that personhood isn't a human monopoly - we are surrounded by what Irving Hallowell called "other-than-human persons" - then takes it further. These persons (which, with the new materialism, Rubenstein argues include the supposedly "inanimate") sympoeitically constitute each other in relations. This world of relations, glimpsed at various points by various thinkers and given a scientific pedigree by relativity and Karen Barad's Bohrian concept of "intra-action," is one of the things Rubenstein's "pantheologies" propose.

Another pantheological proposal is that the universe necessarily eludes our totalizing imagining because it is perspectival. Rubenstein grabs Spinoza at both ends: deus, sive natura is only the tip of the iceberg, since God has an infinite number of attributes, not just two. But these attributes, while infinite, are also in some way contingent, as the "modes" through which they manifest somehow manage to be. It's dizzying and delirious and disconcerting ... and divine. Pantheism, reclaimed from the panic of the polemicists and from the hesitation of its prophets, discloses a world of vibrant stuff which makes most theisms seem human all too human. And it's better than atheism, she argues, because it generates awe, mutual responsibility, and wrests reality from the dead hand of monotheistic hierarchies and their soulless secularized successors (184-87).

It's an exciting book, and I thrilled to learn new things, revisit old ones, and see them brought into such a dynamic and multi-faceted conversation. In recent years I've drifted away from intense engagement with the western intellectual history, and this book both showed profound new problems within it and introduced a community of heretics and visionaries who demonstrated you could do brilliant things with its terms, monstrous and wondrous things neither boosters nor critics have thought of. Maybe all those things I used to know may serve some purpose in this decolonial Anthropocene era after all, I found myself thinking, gratefully. Maybe the energetic affinities I've sensed with material from other traditions and perspectives are more than figments of my halting imagination.

But has this book changed my life? It's too early to tell but for now my life seems, for better or worse, mostly unchanged. This is less because so many of the sources, historical and contemporary, engaged in Pantheologies had already seemed promising to me than because its synthesis of them isn't the one I was getting around to making - or resisting making.

This wouldn't surprise Rubenstein, who calls her book Pantheologies precisely to avoid suggesting her perspective is the only one! The point isn't just to start thinking about what a pluralistic pantheism might be, but to invite us to the world(s?) of pluralistic pantheisms. A part of her argument, braided from threads of Spinoza, particle-wave relativity and Amerindian perspectivism (of which more below), is that no account can ever be final, or finally reconciled with all others, and part of the upshot of this is that this should ground a new kind of wonder and engagement.

I get it, sort of, but I don't find myself in the wonder she describes, and not, I think, because I am wedded to the bad old views she helps us see through. (I should hedge my bets here: I'm sure I remain unconsciously beholden to many such problematic perspectives, and am anticipatorily grateful for how Rubenstein's insights will further liberate me from them as they take root in my thinking.) Perhaps it's a difference - to use another notion of James' - of philosophical temperament. The difference in wonders became clear for me in her comfort with something I find simply baffling, the aforementioned Amerindian perspectivism. Here's how she describes it:

as [Eduardo] Viveiros de Castro explains, any being that can call itself a subject "sees itself as a member of the human species" and sees others as nonhuman predators or prey. So, according to the Jurana (Tupi) people of central Brazil, when a jaguar looks at a jaguar, she sees a human being. When that same jaguar looks at a Tupi man, however, she sees a monkey, or perhaps a peccary. ... As it turns out, every other ontic grouping, no matter how mundane, works the same way. From a vulture's perspective, what the Adhanika (Campa) people call maggots are actually grilled fish; from a jaguar's perspective, blood is beer; from a tapir's perspective, mud is a hammock. ... In other words, there are no "substances" at all ... every term is akin to the designation "mother-in-law": any thing is only what it is from the perspective of the one for whom it is that thing. So, as [Tânia Stolze] Lima points out, a Jurana person will not say that it rained yesterday, but that "to me, it rained." After all, in this multiperspectival social system, where "peccaries" see flutes in the things that "humans" judge to be coconuts, it would be hard to say whether it rained from anyone's perspective other than "mine." (137)

I've tried to wrap my mind around "Amerindian perspectivism" before and failed, so maybe I'm just jealous that it makes sense to her. I know there are flocks of scare-quotes in her recounting that everything understands itself as human, and in the familiar sorts of relationships humans have with prey and predators, pleasures and pains: this would be another "mantheism," surely, not obviously better for being attributed to all beings. And it's fantastically suggestive to bring this together with relativity, etc., a shooting the moon of the ultimate significance or insignificance of the human. But the cachet of Viveiros de Castro's fashionable "multinaturalism" bothers me to no end, and I am confused at Rubenstein's comfort with it. With Margulis I want to protest that microbes do not see themselves as members of the human species. And I don't think it's a holdover from the bad old days to want to believe that, for all our different places in the emergent wonders of symbiotic creativity, it rains on all of us alike. Does that make me, ultimately, a monistic pantheist? Perhaps my recoil at certain and comprehensive views, however multiple or perspectival, aligns me rather with the polytheism of James' piecemeal supernaturalism? Pantheism's messiness seems too orderly to me.

I'll keep pondering Pantheologies' arguments, and have generated a significant list of must-reads from its remarkable bibliography. I can't wait to read Rubenstein's other books. But for now, the divinity of the world remains for me piecemeal, opaque.

Sunday, March 07, 2021

The illusion of three-dimensional space

How can I not have known of the German-born American poet Lisel Mueller (1924-2020)? This (which I found shared in someone's Lenten series) is a simply gorgeous poem about the glories of the works of Claude Monet, using words as the painter used brushstrokes to restore and revel in a world of luminous connection and love.

Saturday, March 06, 2021

Friday, March 05, 2021

New world urbanism

It's widely believed that before colonization, Abya Yala was a vast wilderness, a terra nullius. The pre-colonial cities and villages of these lands suffer from historical erasure because to recognize their importance would challenge that narrative. There are many today who live atop Indigenous homes yet know nothing of pre-colonial history.

Thursday, March 04, 2021

In the bag

Some of the pantry bags distributed at Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen today, along with similarly sized bags (all of them heavy) of produce and proteins. It's a shame the need is so great, but a wonder how HASK is able to meet so much of it, and a joy to be able to help.

Wednesday, March 03, 2021

Discovered

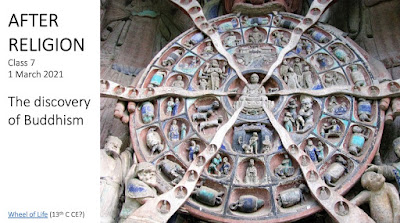

In the Great Discourse on the Lion’s Roar (Mahāsīhanāda Sutta)—a famous text from the Pali canon, the oldest collection of texts and, according to many, the collection that best represents his teachings—the Buddha declares, “Should anyone say of me: ‘The recluse Gotama does not have any superhuman states, any distinction in knowledge and vision worthy of the noble ones. The recluse Gotama teaches a Dhamma [merely] hammered out by reasoning, following his own line of inquiry as it occurs to him’—unless he abandons that assertion and that state of mind and relinquishes that view, then as [surely as if he has been] carried off and put there, he will wind up in hell.” (45-46)

I used this possibility to suggest that 'Buddhism' might offer us excitingly new ways of thinking about history - and about religion. The story of those things people imagine and deride as world religions doesn't have to be a secular one (a secularized Protestant one). This is a version of a point I've made in many classes over the years, but I didn't realize I was setting up in this one. 没想到我会被佛教发现了!

I used this possibility to suggest that 'Buddhism' might offer us excitingly new ways of thinking about history - and about religion. The story of those things people imagine and deride as world religions doesn't have to be a secular one (a secularized Protestant one). This is a version of a point I've made in many classes over the years, but I didn't realize I was setting up in this one. 没想到我会被佛教发现了!Monday, March 01, 2021

PoE20

2001 is the twentieth anniversary of the appearance of my first book, The Problem of Evil: A Reader! I was reminded of this in the sweetest way, by an invitation to speak to a high school class (in San Francisco) which is making its way through it. The class had completed selections from the first three of the book's five sections, and their almost unanimous favorites were, I learned, the Stoics - and their final assignment will be to write their own Encheiridion, based on the excerpts from Epictetus' I'd included in the reader! They'd learned about Stoicism through a rather grim video from the School of Life, a Stoic revival today. Imagine the worst that can happen, it presents Seneca saying to his friends, and realize you can overcome it, if only by ending your life. (Not perhaps ideal material for teenagers...!)

2001 is the twentieth anniversary of the appearance of my first book, The Problem of Evil: A Reader! I was reminded of this in the sweetest way, by an invitation to speak to a high school class (in San Francisco) which is making its way through it. The class had completed selections from the first three of the book's five sections, and their almost unanimous favorites were, I learned, the Stoics - and their final assignment will be to write their own Encheiridion, based on the excerpts from Epictetus' I'd included in the reader! They'd learned about Stoicism through a rather grim video from the School of Life, a Stoic revival today. Imagine the worst that can happen, it presents Seneca saying to his friends, and realize you can overcome it, if only by ending your life. (Not perhaps ideal material for teenagers...!)

Going back to the book, and how I'd defined and executed it, was fun - I haven't revisited that in ages! Fun, too, to remind myself of the colored cover I'd hoped we could have, of a painting I'd seen at a Dosso Dossi exhibition at the Met, to be wrapped around the book so that the messenger Mercury might appear on the spine, his finger to his lips but with eyes full of compassion. The grief of afflicted Justice would fill the front cover, the absorption of Jupiter painting butterflies and cucumber flowers the back, with the community of humans struggling to make sense of things awaiting within.

Going back to the book, and how I'd defined and executed it, was fun - I haven't revisited that in ages! Fun, too, to remind myself of the colored cover I'd hoped we could have, of a painting I'd seen at a Dosso Dossi exhibition at the Met, to be wrapped around the book so that the messenger Mercury might appear on the spine, his finger to his lips but with eyes full of compassion. The grief of afflicted Justice would fill the front cover, the absorption of Jupiter painting butterflies and cucumber flowers the back, with the community of humans struggling to make sense of things awaiting within.