Saturday, December 31, 2022

Friday, December 30, 2022

Family book club

For Christmas, I got copies of a book for my sister in Australia, my parents in California, and us in New York. Billy Griffiths' Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia, not published in the US yet (or perhaps ever), is a book I learned about because my enterprising nephew was doing tech for the first Mountain Writers Festival last month, and Griffiths was one of the speakers. Deep Time Dreaming is a sort of history of Australian archaeology. On the book jacket it promises to investigate a twin revolution: the reassertion of Aboriginal identity in the second half of the twentieth century, and the uncovering of the traces of ancient Australia. It explores what it means to live in a place of great antiquity, with its complex questions of ownership and belonging...

For Christmas, I got copies of a book for my sister in Australia, my parents in California, and us in New York. Billy Griffiths' Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia, not published in the US yet (or perhaps ever), is a book I learned about because my enterprising nephew was doing tech for the first Mountain Writers Festival last month, and Griffiths was one of the speakers. Deep Time Dreaming is a sort of history of Australian archaeology. On the book jacket it promises to investigate a twin revolution: the reassertion of Aboriginal identity in the second half of the twentieth century, and the uncovering of the traces of ancient Australia. It explores what it means to live in a place of great antiquity, with its complex questions of ownership and belonging... Thursday, December 29, 2022

California fusion

流芳園, the Huntington's Chinese garden, is a wonder. Crafted only in the last two decades, it already captures the delight of wandering through the scholars' gardens of Suzhou which are its inspiration.

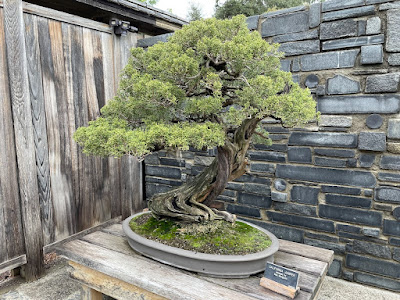

流芳園, the Huntington's Chinese garden, is a wonder. Crafted only in the last two decades, it already captures the delight of wandering through the scholars' gardens of Suzhou which are its inspiration.  Lovely vistas, intimate and distant, around corners and through openwork windows and oddly shaped doors... I was impressed also at the ways it works in its Southern California setting - that cloud-covered hill in the distance, for instance. (The land around Suzhou is flat so all its mountains are fanciful.) And the dark green tree at left is a venerable Coastal Live Oak! Also venerable were the splendid 盆景 penjing (Chinese antecedents to Japanese bonsai) which give the thrill of Suzhou's play with scale.

Lovely vistas, intimate and distant, around corners and through openwork windows and oddly shaped doors... I was impressed also at the ways it works in its Southern California setting - that cloud-covered hill in the distance, for instance. (The land around Suzhou is flat so all its mountains are fanciful.) And the dark green tree at left is a venerable Coastal Live Oak! Also venerable were the splendid 盆景 penjing (Chinese antecedents to Japanese bonsai) which give the thrill of Suzhou's play with scale.Wednesday, December 28, 2022

Calm before the storm

Getty gems

Two insanely detailed small paintings at the Getty, Gerrit Dou's "Astronomer by Candlelight" (1651), 32x21cm, and Jan Brueghel the Elder's "Sermon on the Mount" (1598), 27x37cm. Like in a Persian miniature painting my eye couldn't make out the brushwork.

Getty high

|

Tuesday, December 27, 2022

Master strokes

An "atmospheric river" brought rain to California today, including the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, where we're starting a short Los Angeles trip which looks to be heavy on European Old Masters. Moved by Jan Davidzoon de Heem's perfectly poised "Vase of Flowers" (mid-1670s), Van Gogh's exploding "Mulberry Tree" (1889), and Jusepe de Ribera's tender "The Sense of Touch" (1615-16).

An "atmospheric river" brought rain to California today, including the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, where we're starting a short Los Angeles trip which looks to be heavy on European Old Masters. Moved by Jan Davidzoon de Heem's perfectly poised "Vase of Flowers" (mid-1670s), Van Gogh's exploding "Mulberry Tree" (1889), and Jusepe de Ribera's tender "The Sense of Touch" (1615-16).

Sunday, December 25, 2022

Saturday, December 24, 2022

Thursday, December 22, 2022

Otherworldly ascents

Visitors can look inside the largest, a great cavern dominated by the massive Hale telescope, with which astrono-mers made discoveries beyond imagining. Like quasars! One revealed that most galaxies - including our own - have a black hole at their center. Those wavy lines at lower right in this illustraion show where scientists trained Hale's eye. The illustration is in the little museum nearby, which is overshadowed by

Visitors can look inside the largest, a great cavern dominated by the massive Hale telescope, with which astrono-mers made discoveries beyond imagining. Like quasars! One revealed that most galaxies - including our own - have a black hole at their center. Those wavy lines at lower right in this illustraion show where scientists trained Hale's eye. The illustration is in the little museum nearby, which is overshadowed by  a more terrestrial wonder, a perfect cone of a tree which turned out to be a juvenile giant sequoia! I didn't know these other symbols of transcendance could grow anywhere but the flanks of the Sierra Nevada, certainly not in our southern California neighborhood. Wormholes in space and time...! The local wildlife saw an unexpected opportunity: the far side of another sequoia, on the other side of the museum, turned out to be a woodpeckers vault, embedded with acorns. Worlds within worlds!

a more terrestrial wonder, a perfect cone of a tree which turned out to be a juvenile giant sequoia! I didn't know these other symbols of transcendance could grow anywhere but the flanks of the Sierra Nevada, certainly not in our southern California neighborhood. Wormholes in space and time...! The local wildlife saw an unexpected opportunity: the far side of another sequoia, on the other side of the museum, turned out to be a woodpeckers vault, embedded with acorns. Worlds within worlds!Wednesday, December 21, 2022

Saintly trees

Tuesday, December 20, 2022

Monday, December 19, 2022

Facing oblivion

Saturday, December 17, 2022

Breaking

Haven't been on the Broken Hill trail at Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve in a while (I think it was closed for a time), and it didn't disappoint. I think it must be called Broken Hill because, from a distance, it looks like a chunk's been knocked out of a ridge. But look to the north and you see it's also breaking in real time, the chunky orange has all recently fallen on the sinuous yellow sandstone.

Haven't been on the Broken Hill trail at Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve in a while (I think it was closed for a time), and it didn't disappoint. I think it must be called Broken Hill because, from a distance, it looks like a chunk's been knocked out of a ridge. But look to the north and you see it's also breaking in real time, the chunky orange has all recently fallen on the sinuous yellow sandstone.

Friday, December 16, 2022

Aftershocks

As a terribly trying semester ends, plans are afoot for change on many levels - though not by our top leadership, which remains mum, unwilling to concede any mistakes were made. The One New School coalition, anchored by students and forged in support for the part-time faculty striking for a fair contract, is wrapping up this stage of an occupation of our signature building with the inauguration of a prophetic new identity for the university. (Their graphic designer seems to understand what a tall order unifying this fractured and fractious community is!) The recently-founded Mellon Initiative for Inclusive Faculty Excellence has produced a visionary critique of the university's entrenched white supremacist culture. And my college may be the first faculty body with the guts to join the One New School in voting no confidence in the leadership and board of trustees (faculty have until tomorrow night to vote). As Bette Davis' character says in "All about Eve," Fasten your seat belts. it's going to be a bumpy ride.

As a terribly trying semester ends, plans are afoot for change on many levels - though not by our top leadership, which remains mum, unwilling to concede any mistakes were made. The One New School coalition, anchored by students and forged in support for the part-time faculty striking for a fair contract, is wrapping up this stage of an occupation of our signature building with the inauguration of a prophetic new identity for the university. (Their graphic designer seems to understand what a tall order unifying this fractured and fractious community is!) The recently-founded Mellon Initiative for Inclusive Faculty Excellence has produced a visionary critique of the university's entrenched white supremacist culture. And my college may be the first faculty body with the guts to join the One New School in voting no confidence in the leadership and board of trustees (faculty have until tomorrow night to vote). As Bette Davis' character says in "All about Eve," Fasten your seat belts. it's going to be a bumpy ride.

Wednesday, December 14, 2022

Tuesday, December 13, 2022

Trunk-ated

I'm pasting in a picture that could be a hopeful representation of what this semester might turn out to have been. It's a redwood I saw on a walk up Volcan Mountain in San Diego a few years ago.

I'm pasting in a picture that could be a hopeful representation of what this semester might turn out to have been. It's a redwood I saw on a walk up Volcan Mountain in San Diego a few years ago.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)