Wednesday, July 30, 2025

Sacred grove

Saturday, June 28, 2025

SBMA

Two works from the lovely Santa Barbara Museum of Art resonate with my experience bringing reflections on the religion of trees to the ISSRNC. On the one hand, it felt a little like the teeny tiny artist - painting a tree - oblivious to the all-enveloping weeping woman in David Alfaro Siqueiro's "The Aesthete in Drama" (1944); his canvas is about the size of each of her welling tears. Is focusing on trees irresponsible sentiment-ality in the face of climate catastrophe?

Two works from the lovely Santa Barbara Museum of Art resonate with my experience bringing reflections on the religion of trees to the ISSRNC. On the one hand, it felt a little like the teeny tiny artist - painting a tree - oblivious to the all-enveloping weeping woman in David Alfaro Siqueiro's "The Aesthete in Drama" (1944); his canvas is about the size of each of her welling tears. Is focusing on trees irresponsible sentiment-ality in the face of climate catastrophe?

Monday, May 26, 2025

Book end

And found a phrase I might use as an epigraph:

We are taught that using a plant

shows respect for its nature

Saturday, May 24, 2025

Converse

Inspired by the example of our alum, who told of a "mind-blowing" religious conversation with ChatGPT, I had a friendly conversation with the new Claude. By friendly I mean not testing it, trying to catch it out in hallucinations or bias, or using it for nonsense prompts. Perhaps a better word is "credulous"? Or "suspension of disbelief"? In any case, if the result was not mind-bending, it certainly powerfully tugged at my theory of mind. My disbelief is in suspense!

Someone way back at that IT event two years ago suggested that people ought to try working with it in the areas they know best before dismissing AI, something I've half-heartedly tried for theory of religion, but this time I tried what's closer to my heart, religion of trees.

Actually, I started a few days ago with the newest free version of ChatGPT, which was very informative - but a little pushy. After its multi-pointed response to every question I posed (the content very good, by the way, the tediously predictable form somewhat leavened by pleasing emojis), it always ended with action points. Did I want its help doing A or B? I felt myself pushed not to linger but to get on with things. Research - done! Now: action! In short order it had offered me a menu of options for designing a "personal tree reverence ritual."

Where on earth did it lift all this? Whatever the sources, my students would eat this up! I imagined them leaping from their seats, empowered and inspired to assemble materials for an engagement with the courtyard maples, with just enough examples to define a space within which they might develop something meaningful and yet their own.Trying to slow it down I expressed some misgivings about how such gestures might be self-indulgent, not making meaningful relationship with trees but distracting me from the more demanding relationships with my fellow humans. It commended me for asking courageous questions, adding that very few people thought this far. This was going to my head. Shuddering to think what the paid subscription versions might add, but also suffering from information overload, I called it a day.

Claude was a different experience. It had its share of appreciative responses to the "hard questions" I dared to ask but was neither as sycophantic nor as pushy as ChatGPT. Its format and aesthetics are more congenial to me, so it felt more like an open-ended conversation than a consultation. It really mimicked conversation, too. As I responded to particular of its phrases, it responded to some of mine. Pretty quickly it got pretty deep. I tried out a thought percolating since the penultimate session of "After Religion" - that AI might help us overcome human myopia rather than further estrange us from the rest of the living world. Here's what happened. (Claude's responses were quick, if pleasingly not instantaneous, I often took time between my prompts, both because I wanted to keep them to a minimum, knowing their ecological cost, but also because it was such interesting stuff; at several points I sent a response to a friend, a big AI-skeptic, for his thoughts.)

Tuesday, April 22, 2025

Forest rain and forest fires

One of the final sessions of "Religion and Ecology: Buddhist Perspectives" almost became a religion ot trees class today. I'd chosen three final readings from the old anthology Dharma Rain: Sources of Buddhist Environmentalism - the passage from the Lotus Sutra which gave the anthology its name, an essay on "the religion of consumerism" from Sulak Sivaraksa's 1991 Seeds of Peace: A Buddhist Vision for Renewing Society and Gary Snyder's semi-serious "Smokey the Bear Sutra" of 1969.

The "Medicinal Herbs" fascicle of the Lotus Sutra argues that the limitless Dharma, like a soaking rain which lets each and every kind of plant thrive, naturally expresses itself in a variety of teachings suitable to the variety of suffering beings. I was hoping that would allow us to sense a wide and still unfolding tradition in Sivaraksa's critique of consumerism in Thailand as well as Snyder's revelation of Smokey the Bear as a kind of Dharma protector for Americans.

Discussion of the Lotus section went well enough. A student from Pakistan helped us appreciate the text as written in a monsoon climate, to which I added that the "inferior, middling and superior" medicinal herbs and small and large trees to which the Lotus likens beings of different levels of enlightenment should be understood as constituting a forest, each part of which was distinct and necessary - herb, understory, canopy. Even the tallest trees can't provide the healing of ground-hugging medicinal herbs, though they provide shade for them. So far so good. The "Dharma rain" wasn't just offering each individual something that worked for them, but sustained a whole interconnected world.

But if religion and trees was helping here, students weren't having it come Smokey. Zen poet Snyder revalues the familiar U. S. Forest Service mascot, whom the Buddha "once in the Jurassic about 150 million years ago" announced would be his "true form" in our time:

... Bearing in his right paw the Shovel that digs to the truth beneath appearances, cuts the roots of useless attachments, and flings damp sand on the fires of greed and war;

His left paw in the mudra of Comradely Display—indicating that all creatures have the full right to live to their limits and that deer, rabbits, chipmunks, snakes, dandelions and lizards all grow in the realm of the Dharma;

Wearing the blue work overalls symbolic of slaves and laborers, the countless men oppressed by a civilization that claims to save but often destroys; ...

Trampling underfoot wasteful freeways and needless suburbs, smashing the worms of capitalism and totalitarianism...

Fun, huh? The students tasked with leading the discussion on this weren't having it. "We all hate Smokey the Bear!" they cried. Why? He's so commercialized! He represents the settler colonial effacement of indigenous peoples! He's the emblem of the fire suppression strategies which generate mega fires! He anthropo-morphizes the non-human world! The real Smokey bear cub was rescued from a fire only to spend the rest of his life in a cage! He makes tourists endanger themselves thinking real bears are warm and cuddly!

Did you read beyond the title, I asked? Snyder isn't actually much more interested in forests than the Lotus Sutra is. It's a metaphor, a skilful means... They assured me they hated Snyder too, whom we've critiqued for claiming he had become a "Native American." When I observed that Synder was one of the models for Kerouac's Dharma Bums one volunteered "I hate the Beatniks!"

This conflagration of Smokeyphobia caught me by surprise. Synder's "Sutra" is celebrated among American Buddhists, appearing in the HDS "Buddhism through its Scriptures" MOOC as well as the Norton Anthology of World Religions, not to mention Dharma Rain. But clearly what was a skilful means for older generations wasn't working for these students.

I tried to let this be the takeaway of our discussion. Smokey's clearly not the medicine we need now. But the forest is full of plants. "What might a more skillful metaphor be?" Our class time had sadly run out. But I think we were all struck by the ferocity of the reaction to the "Smokey the Bear Sutra." That must be telling us something. Perhaps it's the effrontery of the generations which destroyed the environment telling children "Only YOU can prevent forest fires." On Earth Day no less!

Friday, March 07, 2025

Gardener divine

.jpeg) A friend asked how my trees were doing. It's been a busy schedule of teaching and other duties, I reported, but I do have snippets of time for my book project. I looked at the courtyard maples, ready to pop. Share something fun you found, she asked?

A friend asked how my trees were doing. It's been a busy schedule of teaching and other duties, I reported, but I do have snippets of time for my book project. I looked at the courtyard maples, ready to pop. Share something fun you found, she asked?

Ok, said I. Someone's recently published a book debunking the received

explanation for how the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden came to be

identified as an apple (after centuries as a fig, grape or

pomegranate). As part of his research he compiled a website of images of the fateful scene, one of which delights me to no end.

It's from a 9th century French illustrated Bible known for where it now resides as the Bamberg Bible, although in Bamberg it's referred to as the Alkuin-Bibel. Anyway, the illustrations facing the Book of Genesis are out of this world. The depiction of the eating of the forbidden fruit in the second row clearly shows a fig tree - and it's leaves from that same tree that Adam and Eve use to cover their nakedness. But beyond the exquisite beauty of the whole thing, something else caught my eye.

It's from a 9th century French illustrated Bible known for where it now resides as the Bamberg Bible, although in Bamberg it's referred to as the Alkuin-Bibel. Anyway, the illustrations facing the Book of Genesis are out of this world. The depiction of the eating of the forbidden fruit in the second row clearly shows a fig tree - and it's leaves from that same tree that Adam and Eve use to cover their nakedness. But beyond the exquisite beauty of the whole thing, something else caught my eye.

It's in the first row, which shows the creation of Adam and then, in a gorgeous explosion, of other animals. This is the sequence of the second creation account, where the man is clearly created to take care of the garden (2:15), indeed even before the Garden of Eden is planted.

But look at the trees in that top row. They've all been pruned! That's how, I'm suggesting, everyone used to know that well-tended trees looks like. Trees in this world don't take care of themselves. If Adam is made in God's image (1:27), it's in the image of a gardener!

Sunday, December 15, 2024

No man is an island

And back to California for the holidays! The movie player on the seat in front of me wasn't working so I had a chance to delve into Dharma Rain: Sources of Buddhist Environmentalism (2000) - just what I needed to start pondering my upcoming spring "Religion and Ecology" class, which I've promised will center "Buddhist perspectives." One very happy discovery, a short work by Japanese monk and visionary 明恵 Myōe (1173-1232) entitled "Letter to an Island," enacts the nonduality of animate and inanimate, Buddha and the rest, by addressing an island (conveniently if coincidentally called Karma) Myoen knows from childhood.

Dear Mr. Island, it begins, How have you been since the last time I saw you? After I returned from visiting you, I have neither received any message from you, nor have I sent any greetings to you. then swiftly moves into preaching: I think about your physical form as something tied to the world of desire, a kind of concrete manifestation, an object visible to the eye, a condition perceivable by the faculty of sight, and a substance composed of earth, air, fire, and water that can be experienced as color, smell, taste, and touch. Since the nature of physical form is identical to wisdom, there is nothing that is not enlightened. Since the nature of wisdom is identical to the underlying principle of the universe, there is no place it does not reach.

So Mr. Island isn't distant or even really an island, but assuredly a friend! After a little more learned disquisition, Myōe becomes personal again.

Even as I speak to you in this way, tears fill my eyes. Though so much time has passed since I saw you so long ago, I can never forget the memory of how much fun I had playing on your island shores. I am filled with a great longing for you in my heart, and I take no delight in passing time without having the time to see you.

And then there is the large cherry tree that I remember so fondly. There are times when I so want to send a letter to the tree to ask how it is doing, but I am afraid that people will say that I am crazy to send a letter to a tree that cannot speak. Though I think of doing it, I refrain in deference to the custom of this irrational world. But really, those who think that a letter to a tree is crazy are not our friends. ...

This would make a nice bridge from "Religion of Trees"!

Myoe, "Letter to the Island," trans. George J. Tanabe, Jr., in Dharma Rain: Sources of Buddhist Environmentalism ed. Stephanie Kaza and Kenneth Kraft (Boston and London: Shambalah, 2000), 63-65; portrait of Myōe in a tree from Kōsanji, Kyoto

Sunday, December 01, 2024

Windfall

Tuesday, November 12, 2024

High-callery

Just a leaf from a big callery pear on West 12th Street. From below, the callery pears seem not to have noticed the change of season, their leaves apparently all green and glossy. Only from a distance does one realize their canopies are already a deep burgundy which, on closer inspection beneath the tree, is mostly dramatic reds and blacks.

We'd read about callery pears in David Haskell's The Songs of Trees for today's "Religion of Trees" class. Their leaves are remarkably unscarred by insects because the tree is a hybrid, its progenitor brought to the US from China when existing American pear trees were decimated by a blight, and remains resistant to local bugs. Values have changed since they were introduced, however, Haskell observes, as we now think more about supporting local populations of pollinators. (And fewer bugs means fewer birds.) Callery pears, besides being high-maintenance and prone to drop branches, seem uncivil.

Most street trees' existence is solitary and difficult, but I was struck by the loneliness of this virtually untouched leaf.

Friday, November 01, 2024

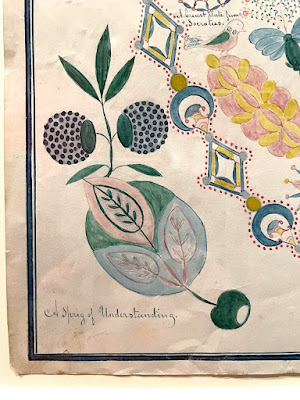

Sprigs of understanding

What a pleasure to find at the American Folk Art Museum the originals of some of the Shaker Gift Drawings I found reproduced in a book when we visited Canterbury Shaker Village last year! This "Sprig of Understanding" appears in Polly Jane Reed's "A Present from Mother Lucy to Eliza Ann Taylor" (1849), one of several drawings in which every image is labeled.

What a pleasure to find at the American Folk Art Museum the originals of some of the Shaker Gift Drawings I found reproduced in a book when we visited Canterbury Shaker Village last year! This "Sprig of Understanding" appears in Polly Jane Reed's "A Present from Mother Lucy to Eliza Ann Taylor" (1849), one of several drawings in which every image is labeled.

Some trees from drawings already shared with this blog:

Some trees from drawings already shared with this blog:

A new one: Polly Collins' "The Gospel Union, Fruit-Bearing Tree" (1855)

It's not all trees, of course, most conspicuously in Semantha Fairbanks and Mary Wicks' "Sacred Sheet"(1843), a calligraphy of tongues!

Sunday, September 29, 2024

Tree planting

Had the great pleasure today of leading the Adult Forum at Church of the Ascension on "Trees and the Sacred." It was nice not just to share my thinking with a new audience, but to do so at the place where the original seed for the whole project may have been planted. It was at one of their Sunday evening Services of Meditation and Sacrament years ago that I first heard Thomas Merton's words

A tree gives glory to God by being a tree...

Since Ascension, like our church, has been using the special Prayers of the People distributed as part of this month's Season of Creation, I built our discussion around that. We started a round of self-introductions - include "a special tree, a particular tree or tree species" - which elicited all manner of tender stories of relationships with trees. (Recalling that the Anishinaabe call trees "the standing people"I quipped that we'd more than doubled the number of people in our room.) Then I passed out a copy of the Prayers and asked people to find the trees in it. There are none, of course, though "forestry and timber-harvesting" are mentioned. "Indirectly they're everywhere," someone protested.

Since Ascension, like our church, has been using the special Prayers of the People distributed as part of this month's Season of Creation, I built our discussion around that. We started a round of self-introductions - include "a special tree, a particular tree or tree species" - which elicited all manner of tender stories of relationships with trees. (Recalling that the Anishinaabe call trees "the standing people"I quipped that we'd more than doubled the number of people in our room.) Then I passed out a copy of the Prayers and asked people to find the trees in it. There are none, of course, though "forestry and timber-harvesting" are mentioned. "Indirectly they're everywhere," someone protested.

I told them of my distress at discovering the unspoken taking for granted of plants and trees, but also offered a way forward. Turns out these prayers were written about ten years ago, and it's only in these past ten years that our minds have been opened to trees in a big way: Braiding Sweetgrass (2015), The Hidden Life of Trees (2016), The Overstory (2019), In Search of the Mother Tree (2021). Were someone crafting those prayers this year, I suggested, of course they'd include the trees!

I used this as a way of arguing we're at a turning point in our relationships with trees, and not the first. For most of human history, our relationship could be characterized as one of dependence - which calls forth gratitude and care, but, human relationships suggest, anxiety and dissembling too. Next came distance - the forgetting of our constant needy interactions with trees made possible by fossilized trees, although we think of them just as minerals, and start to imagine human life as separate and separable from the rest of life. That illusion of distance is what makes it possible to encounter trees as our introductions had showsn us we do, as unexpected friends, silent witnesses and special companions. Our resonance with trees surprises and delights us because we have forgotten we're in deep relation already. The new phase I called shared destiny, and it partakes both of the growing sense of kinship which work of the last decade has helped us see and feel, and the Anthropocene reality that the consequences of our actions (mainly fueled by fossilized trees!) have created a new and shared precarity for tree people and human people.

We finished back with the Prayers for the People: I invited people to amend them, to "plant trees" in the text, whether by changing or adding words or adding a whole new section. Folks came up with a variety of brilliant ways to do so, corresponding to different understandings of the role of trees in creation. "Creatures" should be replaced with a phrase evoking all the forms of life on earth. Trees and plants make a mineral world livable for animals. Trees, givers of life and beauty, merit our thanks and care. What a delight!

And what fun to be in a church, where, instead of presenting my views in a neutral, secular, implicitly naturalistic way, I could be theological. For instance observe that the discovery of plant intelligence has made clear that ours is just one kind of intelligence - an argument I rehearsed in class two weeks ago - and then add that this might allow us to "triangulate" in theological ways. Or share my experience with the wood of the simple cross used in the Good Friday service, since the cross was the most intimate witness of Christ's passion...

Hope I have further chances to tap into the religion of trees of more congregations!

Thursday, September 12, 2024

Buddhist-Daoist forest

A celebrated writer at Renmin University, in whose summer school I taught for a few years, was described to me as an international literary star. His works - dark satires of contemporary Chinese life - were not published in China, but somehow this didn't seem to be a problem. His newest novel (at least in translation) lampoons the program Renmin runs for leaders of China's five officially recognized religions. I've only read about a fourth of it so far, but it's savage. Grimly funny, too, and occasionally unexpectedly lyrical. Two main characters, a young Buddhist nun and a young Daoist priest, sort of fall in love, something she makes sense of through elaborate paper cuts imagining a relationship between the bodhisattva Guanyin and Laozi. Fascinating! But I didn't expect it might involve trees, too...!

A celebrated writer at Renmin University, in whose summer school I taught for a few years, was described to me as an international literary star. His works - dark satires of contemporary Chinese life - were not published in China, but somehow this didn't seem to be a problem. His newest novel (at least in translation) lampoons the program Renmin runs for leaders of China's five officially recognized religions. I've only read about a fourth of it so far, but it's savage. Grimly funny, too, and occasionally unexpectedly lyrical. Two main characters, a young Buddhist nun and a young Daoist priest, sort of fall in love, something she makes sense of through elaborate paper cuts imagining a relationship between the bodhisattva Guanyin and Laozi. Fascinating! But I didn't expect it might involve trees, too...!

Thursday, August 15, 2024

Sunday, August 11, 2024

Clouds of witnesses

Am I child of the mountains? Especially because my "Sacred Mountains" class follows in the footsteps of a course taught by a Sherpa, I've been acutely aware of my distance from mountains. I tell people - and have been telling myself - that mountains are for me things that you need to go out of your way to encounter or even see. I grew up facing the ocean, I say ...

I was never living in the mountains, in the not insignificant part of the world where everything is mountain, so the language of mountain is too broad. I never had the experience one of my students says her mother grew up with in Colombia, where "mountains and people weren't separate" even in thought, and every day began with checking the mood of the mountain. From the flatlander perspective I've too quickly assumed, mountains are exceptions, jutting from - breaking hierophanically through! - a presumably flat world. They're paradigmatically solitary. It even makes sense to think of them as having come from above, from the sky, from outer space. ...

The post describes a conversation with a friend who helped me realize

that there's been a cloud of mountain witnesses attending me all my life, content to let me think they were at my beck and call. Not a mountain child, no. But not just a beach bum either. The time of mountains is one I've sensed...

I suppose I do enjoy playing the Southern Californian naif, the mountain and forest-deprived child of the coastal desert, more at home with the geological than the biological, tempted by the "flatlander" perspective in which every vertical thing is a hierophany - though also aware that everything changes. The Reclus:

A l’esprit qui contemple la montagne pendant la durée des âges, elle apparait flottante, aussi incertaine que l’onde de la mer chassée par la tempète: c’est un flot, une vapeur; quand elle aura disparu, ce ne sera plus qu’un rève.

Meanwhile, the rain came to Lake Henshaw just as we did.

Friday, August 02, 2024

Olympics anyone?

Tuesday, July 23, 2024

Abssyrian arboretum

The Assyrian sacred tree came in many forms, some even (to my eyes) arboreal! But is it, as some eager dendrolators assert, a tree of life, like the one we encounter in Genesis? In the absence of any textual evidence, all that's clear is that it's a symbolically charged date palm, though later versions add fruit, including pomegranates.

Wednesday, July 17, 2024

I bind unto myself today

Some people brought a blind man to [Jesus] and begged him to touch him. He took the blind man by the hand and led him out of the village; and when he had put saliva on his eyes and laid his hands on him, he asked him, ‘Can you see anything?’ And the man looked up and said, ‘I can see people, but they look like trees, walking.’ Then Jesus laid his hands on his eyes again; and he looked intently and his sight was restored, and he saw everything clearly. (Mark 5:22-5, NRSV)

The "religion" part of "Religion of trees" finally clicked today, or clicked into place, as I was mapping out the final chapter. My interest really hasn't been in what is usually celebrated or deplored as "worship of trees," though I devote a chapter to the construct of "the sacred tree," and offer novel takes on the Bodhi tree, the Tree of Life in the Heavenly Jerusalem and Christmas trees. I try to suggest that it's entirely unsurprising that trees in their prodigious variety provided material and metaphorical material for human religious traditions, since they provided such material for every part of human life and culture. But to see that one needs to get beyond monolithic western ideas of trees, and of our relationships with them, especially in the age of fossil fuels. We're a lot less like trees than facile romantic ideas about our kinship as vertically oriented beings reaching from the earth toward the sky might suggest, and a lot more dependent on them than we may care to admit. The relationships are all of them asymmetrical, and yet in many cases symbiotic.

And so: religion? I remembered one of the folk etymologies of religion as tracing to re-ligare, to re-bind. I used, long ago, to teach Wilfred Cantwell Smith's The Meaning and End of Religion, which argued that the Latin religio was long an obscure and unimportant word, only in modern times and unhelpfully applied to faith traditions. He mentions this along with a competing ancient etymology, re-legere (to re-read), but his point is that there's no clear source and even if there were the term is ultimately unilluminating. My generation of religious studies scholars takes the limitations of the term "religion" for granted.

But this hasn't stopped theologians from claiming one or other of these etymologies as revealing the true meaning of religion, and, while they are wrong to claim a clear etymology, they often make interesting points. I feel like joining them - though of course I'll mention that the history is obscure. Good pragmatist, I'll suggest that etymology can't settle the question, but thinking of religion as re-ligare may be helpful for thinking about humans and trees.

So: helpful - why? Because human life, like every form of life, emerged in ecosystems of tangled interdependence with myriad symbiotic species. Trees were among these symbionts, and, if they had hundreds of millions of years without us, they're stuck in relationship with us for the foreseeable future, and we with them. Pretending otherwise is historically wrong and politically and spiritually unhelpful. We must reduce our carbon and other footprints but a world from which human beings could discreetly withdraw is a dangerous fantasy. What's needed is rediscovering, reviving, re-imagining our relationships with trees. And not from a distance, but in embodied relationships of giving and taking.

Okay, so undoing the "severing of relations," which Heather Davis and Zoe Todd have convinced me is the fatal colonial heart of the Anthropocene, could be linked to re-binding, religare. (I stumbled on this thought once before.) But why not just talk about relationships? Because most of our modern ideas of relationships are premised on ideas of reciprocity, mutuality, balance which are thwarted by the assymmetries of our relationships with trees: for starters they're so much slower and bigger and older than we, and we take so much more from them than we could ever give back.

But that's maybe where we need "religion." One needn't go all the way to Schleiermacher's "feeling of absolute dependence" or Otto's "wholly other" to see religion (or practices and ideas we gather under that name) as allowing us to name relationships in which reciprocity doesn't even make sense. It's a little like Aldo Leopold's learning to "think like a mountain," where the predation of wolves is discovered to be necessary to keep deer populations from ravaging forests, but more like Skywoman's cosmogonic dance of gratitude at the sacrifice of muskrat, who, at the cost of his life, brought the little pawful of mud from which our world was made, along with the gratuitous generosity of our fellow nonhuman kin. The dance matters.

Men are not like trees, walking (or not walking). But we live - we are able to live as humans, to dance - with and because of them. Ethics and economics can't begin to frame so profound a relationship.

Friday, July 12, 2024

Trees of religion

This is the most elaborate "tree of religions" I have found. The work of an obscure foundation based in Vienna, it traces all manner of contemporary religious groups (including a solar flare of Shinto in yellow at left) to a common trunk of coiling "Early Vedic Period" (brown), "Shramanic Traditions [Non-Vedic]" (purple), "Ancient Israelite Religion" (magenta), "Chinese Folk Taoism" (green) and "Japanese Mythology" (grey). Monotheisms fill out about two-thirds of the tree on the right, with Judaisms at the center. A little different and both more pluralistic and less inclusive than an earlier "evolutionary tree of religions" we've seen, which traces everything to animisms, but similar claiming a kinship of all traditions - all but a few of which are derivative.

This is the most elaborate "tree of religions" I have found. The work of an obscure foundation based in Vienna, it traces all manner of contemporary religious groups (including a solar flare of Shinto in yellow at left) to a common trunk of coiling "Early Vedic Period" (brown), "Shramanic Traditions [Non-Vedic]" (purple), "Ancient Israelite Religion" (magenta), "Chinese Folk Taoism" (green) and "Japanese Mythology" (grey). Monotheisms fill out about two-thirds of the tree on the right, with Judaisms at the center. A little different and both more pluralistic and less inclusive than an earlier "evolutionary tree of religions" we've seen, which traces everything to animisms, but similar claiming a kinship of all traditions - all but a few of which are derivative.

Thursday, July 11, 2024

Pre-eminent trees

It's only just hit me. Mircea Eliade says nice things about trees: "the tree came to express everything that religious man regards as pre-eminently real and sacred.” But I hadn't connected this, which comes in the third chapter of The Sacred and the Profane (149), the chapter summarizing Patterns in Comparative Religion, to the thematics of the more influential preceding two chapters on "sacred space" and "sacred time."

In the former, "Sacred Space," Eliade argues for humans' existential need for "orientation," something furnished only by an "irruption of the sacred" which creates a "center of the world." Without a center (or centers: there can be many), there's nothing but the "chaos of relativity" - as modern man adrift in a "desacralized" world knows. Preeminent among centers are the "axes mundi" of sacred mountains and "cosmic trees," the models for all the smaller-scale centers of temples and dwellings. The Sacred and the Profane famously tells of an Aboriginal tribe whose sacred pole, carved from a gum tree, broke and, unable to continue living, lie down to die (33) - a story as famously debunked in Jonathan Z. Smith classic "The Wobbling Pivot."

The second chapter, "Sacred Time," summarizes the argument of The Myth of the Eternal Return. Its upshot is that time is a corrosive force, something all but modern people know. "History is suffering," he writes in Myth. Accordingly the ritual systems and myths of almost all religions know the world must be regularly refreshed, indeed recreated.

Well, who offers an axis mundi and also recreates the world every year? Only trees do! Uniting the upper and lower worlds Yggdrasil-style, "the tree represents – whether ritually and concretely, or in mythology

and cosmology, or simply symbolically – the living cosmos, endlessly

renewing itself" (Patterns, 267). (Well, trees are just trees, just as stones and mountains are just stones and mountains, but when they present themselves as "sacred" are loci of experience of the really "real"; the "sacred" is always "camouflaged" in the "profane." But still, sacred space and sacred time together?!

Eliade's thought is passé, at least among scholars of religion. We distrust his universalizing "comparative" method and hear fascist echoes in his criticisms of modern life and thought and whispers about "the pre-eminently real and sacred." But beyond the academy his ideas continue to appeal. How much oxygen should I give them in my book? I don't believe in the sort of universal religiosity he peddles, and am at pains to argue that different species of trees are widely different and have accordingly meant widely different things to people through their relationships with them.

But the idea of the cosmic tree, triangulating sacred space and sacred time, seems to point to something worth pondering. If not a fact about trees, this frisson of "sacred time" and "orientation" might register a fact about some of us, a frisson worth cultivating or overcoming.

Tuesday, July 02, 2024

Step softly

As I move closer to engaging the many others who write about religion and trees (though none in the way I do) I'm finding it a little hard to avoid sounding peevish. It's not that they're wrong, though I think their views are often naive, but they're going about things the wrong way. (But I really don't like criticizing people...)

Above is a spread from Hannah Fries' Being with Trees: Awakening Your Senses to the Wonders of Nature, a lovely little collection of poems and photographs and contemplative prompts I just got which invites readers to a real or vicarious "forest bathing" experience; it has a foreword by one of my heroes - Robin Wall Kimmerer - and is blurbed by another - David George Haskell. Its premise and promise:

Being in the woods doesn't just feel good but is, in fact, good for you.* (North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing, 2022), 15

and you can experience this whether you are in a city park, town trail system, state forest, national park or private woodland (22). Apparently human beings have always known of the solace and comfort of trees, have always known what Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote:

"In the woods we return to reason and to faith." (19)

But, I want to say peevishly, is that true? One doesn't have to take Robert Pogue Harrison's view that forests are the uncanny other to civilization (itself rather a modern take) to wonder at this sanitized experience of safety and escape from human cares. Isn't the very premise here that we are guests in the world of trees, an assumption that distinguishes us from most of our ancestors? In ways it's taking me pages to enumerate, we are so estranged from the natural world that relationship with trees seems optional. It's definitely better to opt for them than against them, of course! But so much of the tree-lovers' enthusiasm takes separation for granted that real relationship can't really be imagined - the kind of relationships trees have with other species, including, for much of our short history, human beings.

As the trees breathe out, you breathe in; as the trees breathe in, you breathe out. (27)

This is well and good, but the real relationship - a pretty damn lopsided relationship - between us and trees is fleshy, not just airy. More honest acknowledgment of dependence and the difficulty of reciprocity is needed.

Verlyn Klinkenborg makes a similar point with the same words of Emerson:

Only in 1836, when most of the land around Concord, Massachusetts, had been cleared, could Emerson say, “In the woods, we return to reason and faith.”

Klinkenborg distinguishes between the solace offered by individual trees, who echo our own loneliness, and the quite different experience of forests, with whom human beings - especially settler colonists in North America - had had an adversarial relationship. (There are no Native Americans in Klinkenborg's story, alas.)

The literature of forest-fear is endless, and it plucks at something ancestral and still fresh within us. In the forest we feel the power of scale—and perhaps the power of time—almost too vividly. We shrink within ourselves, growing smaller and smaller as the forest grows deeper and taller.

"The Lone Tree Forest," in Diane Cook and Len Jenshel, Wise Trees (Abrams, 2017), 11, 10

Being with Trees acknowledges this feeling of smallness and even threat, but glosses it as the Romantics' sublime.

What place makes you feel both awed and a little fearful at once? (173)

Really, we learn, trees and forests want us to feel good, as connected to all things as as they are. They offer us healing. And the right response is wonder, gratitude, joy! But don't stop there:

Let us choose joy, but let's not stop there. Let your joy and wonder also move you to reverence. As you walk in the woods, think of the ground you walk on as sacred. Make a little mental nod to all the life you encounter, acknowledging each thing as its own small miracle. (179)

Although the trees may offer healing, we will not be fully healed until we, in turn, begin to heal the wounds we have inflicted on our landscapes. We can honor the trees and the earth with our wonder and our reverence, knowing that this is the foundation of a new relationship of reciprocity. (181)

How could I not love this? Especially as the last words are Kimmerer's?

"We are dreaming of a time when the land might give thanks for the people." (185)

I've experienced, gratefully, all the kinds of rapture this book celebrates. And yet it all still seems antiseptic to me, touristic. Wonder and reverence seem too easy, too distant. Redolent of the National Park motto "Take only photographs, leave only footprints." This is indeed how to be a good guest, but not how to be at home in a forest, to be in real relation with its other citizens. Care for the environment is needed, lots of it, but what kind of "new relationship of reciprocity" can come from a wonder and reverence that thinks we can and should leave no footprint?

By footprint I'm meaning, I think, our taking more from trees than a sense of peace and connection or even their generously sweet shade. It's taking their nuts and leaves, taking their sap and bark and, often, taking the whole thing. Animals cannot live without consuming plants, and human society depended on trees for everything from shelter to heat to medicine. The history of human culture is the history of fire, and every fire ever lit consumed wood. (More recently, fossilized wood.)

We can't just amble into a forest and sing

Getting to know you,

Getting to know all about you.

Getting to like you ,

Getting to hope you like me.

Getting to know you,

Putting it my way, but nicely,

You are precisely

My cup of tea!

Getting to know you,

Getting to feel free and easy.

When I am with you,

Getting to know what to say.

Haven’t you noticed?

Suddenly I’m bright and breezy

Because of all the beautiful and new

Things I’m learning about you

Day by day.

Okay, so that's a little peevish (and a little unfair to The King and I, which is wise to the difficulty of relationships)!! But I feel like saying: we're not strangers to trees, nor they to us. And they know that no living thing subsists on wonder and reverence.

So, to go back to that spread at the top (here it is again), they might

share my sense that there's a level of self-deception here which doesn't

bode well for a true relationship of reciprocity.

So, to go back to that spread at the top (here it is again), they might

share my sense that there's a level of self-deception here which doesn't

bode well for a true relationship of reciprocity.

These pages come in the book's first section, "Breathe." (The others are "Connect," "Heal" and "Give Thanks.") Invoking Thich Nhat Hanh is always a good thing in my book. There are ways in which labeling our breathing in and out can attune us deeply to things, within and without, and slow walking is a great way to become aware. It can in some mysterious way heal the world. But this invocation comes after several pages of suggestions for ways of opening ourselves to the otherness of trees and overcoming it through a kind of interpenetrating identification. One of the most basic othernesses of trees is that they aren't mobile, as we are: they don't walk. They breathe, perhaps even

breathe in and think of being rooted, like a tree; breathe out, and think of being light, like a leaf in the wind

but if they think I am solid, that I am free, it's a completely different freedom than an animal's. If they could see this book, they might see the picture telling a different, truer story than human-tree communion: human boots pausing on a tree stump. It's a lovely stump. The lichen on it even makes it look a little (to human eyes) like a view through a forest! But the human pretending to be a tree, however softly she's stepping, is taking the place of a tree, before continuing on her merry way.

Now this book doesn't deny the difference between sessile trees and mobile humans but it never takes it really seriously. In fact it quotes one of my long-favorite tree poems, by Robert Frost, (70-71, in its second section, "Connect"), which is all about the difference... but moves on without really hearing what it's saying. (I'm surprised I haven't posted this poem in this blog; I will sometime soon, and try to articulate what I think it's saying that Being with Trees doesn't get.)

This is probably enough for today. I sound peevish but, I hope, peevish in a good cause, the cause of a truer, more honest reciprocity, real relation.*Actually Fries acknowledges, in her acknowledgments: Also, I am aware that not everyone is comfortable and happy in the forest, and I am deeply grateful that I grew up with the privilege and opportunity to play and wander freely and safely in the woods. (188)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)