Friday, April 30, 2021

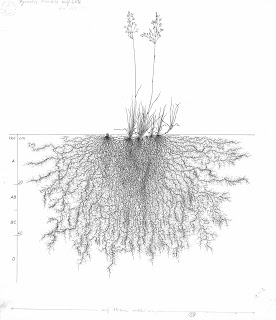

What lies beneath

Thursday, April 29, 2021

As knot is to net

A quite wonderful object has found its way into my world, a big book, ostensibly for children, called The Lost Words: A Spell Book. The work of poet Robert Macfarlane and illustrator Jackie Morris, it's huge - I had to prop it up on the sofa to take a picture. The book appeared in 2017 as a response to a revision of the Oxford Junior Dictionary a decade before, which had made room for new words like "broadband" by eliminating others, based on "the current frequency of words in daily language of children." Among the words dropped were many relating to the natural landscape, and as these omissions were uncovered - fern, raven, kingfisher, ivy, wren, bramble, heron, willow... - public dismay ensued. If these words were no longer much used, oughtn't one, rather, to work to make sure they came back, rather than ratifying their loss?

A quite wonderful object has found its way into my world, a big book, ostensibly for children, called The Lost Words: A Spell Book. The work of poet Robert Macfarlane and illustrator Jackie Morris, it's huge - I had to prop it up on the sofa to take a picture. The book appeared in 2017 as a response to a revision of the Oxford Junior Dictionary a decade before, which had made room for new words like "broadband" by eliminating others, based on "the current frequency of words in daily language of children." Among the words dropped were many relating to the natural landscape, and as these omissions were uncovered - fern, raven, kingfisher, ivy, wren, bramble, heron, willow... - public dismay ensued. If these words were no longer much used, oughtn't one, rather, to work to make sure they came back, rather than ratifying their loss?

Hence this book, which conjures back these "lost words" with gorgeous images and, for each one, an acrostic poem - "a spell" - to restore the word to its lived splendor. It always begins with a riddle - the letters of a word hidden among natural shapes - and continues through a "spell," facing a portrait of the thing itself on gold leaf, to a double-page spread of the thing in its natural setting.

The first suite of images and poem establish the whole project. Conveniently, if shockingly, the alphabetically first of their "lost words" is one it boggles the mind anyone could have thought dispensable: acorn. This is Macfarlane's spell for it:

acorn

As flake is to blizzard, as

Curve is to sphere, as knot is to net, as

One is to many, as coin is to money, as bird is to flock, as

Rock is to mountain, as drop is to fountain, as spring is to river, as glint is to glitter, as

Near is to far, as wind is to weather, as feather is to flight, as light is to star, as kindness is to good, so acorn is to wood.

Sublime, profound, and such fun to say... Without ever even having to use the word "oak," we see the worlds which acorns open to us in meaning and promise, microcosm and macrocosm, change and charm. Macfarlane challenges us to consider how important acquaintance with acorns has been for human thinking on all those things - and how bereft we would be, not only of oak knowledge, were the word and its world to vanish. What were those Junior Dictionary editors thinking?!

Wednesday, April 28, 2021

Javitz jabbed again!

Three weeks to the minute later, second jab complete! You're not supposed to take pictures inside but I had to get a picture of my freshly earned sticker, which says VACCINATE NEW YORK: I GOT MY VACCINE AT THE JAVITS CENTER.

Aibo

"After Religion" is almost done! We have a final session next week, a showcase of student final projects (due and presented in discussion sections this week), but there won't be any more occasions for lecture or discussion. And there wasn't much time for a lecture today, either, as we decided to give some of the lecture time to the discussion sections so students had a decent amount of time to present and receive feedback on their projects... and we're supposed to allot class time for course evaluations, too! So we had an absurd half hour. I decided the best use of it would be a google.doc and discussion, so everyone had a chance to contribute in some way, but I prefaced that with a very quick roundup of inspiring things in the course materials for this week. If I keep the section on transhuman religion next time round, I'll make sure I have time to screen and discuss this video, which was linked to in one of our assigned readings.

"After Religion" is almost done! We have a final session next week, a showcase of student final projects (due and presented in discussion sections this week), but there won't be any more occasions for lecture or discussion. And there wasn't much time for a lecture today, either, as we decided to give some of the lecture time to the discussion sections so students had a decent amount of time to present and receive feedback on their projects... and we're supposed to allot class time for course evaluations, too! So we had an absurd half hour. I decided the best use of it would be a google.doc and discussion, so everyone had a chance to contribute in some way, but I prefaced that with a very quick roundup of inspiring things in the course materials for this week. If I keep the section on transhuman religion next time round, I'll make sure I have time to screen and discuss this video, which was linked to in one of our assigned readings.

It shows a Buddhist ritual for aibo, the first generation of robotic AI puppies, programmed to be companions for human beings young and old, with endearing and even "mischievous" features; these robots are especially widely used for very old people living alone, and produce true joy and comfort. It's traditional in Japan to ritually thank the other-than-human companions which have attended us in life - dolls, tools of various trades, etc. - and it makes sense to do so for aibo too. Their relationships with us are not unreal or meaningless just because they are inanimate - if indeed they aren't animate! The article suggests Shinto and Buddhism undergird a willingness to recognize animacy widely in the land of 鉄腕アトム (Astro Boy).

There's more media attention to robotic priests, like the animatronic Mindar (also in Japan), who teaches about the Heart Sutra, but our capacity to bond with robotic dogs (and to create robotic dogs people can bond with) seems a more interesting way into thinking about religion and new technologies. Coming after a section on the wisdom of traditional indigenous ways of knowing and being, which recognize the animacy of the other-than-human world and the necessity of being in just relation with it, this would raise all sorts of cool human-transcending questions. The dots were there to connect this year, too.

Our discussion today was abbreviated but the google.doc helped students imagine an AI bot which would be an amalgamation of religious teachers/mentors (one student quipped it could be called Baha'i Bot), and which everyone seemed keen and ready to learn from. After Religion indeed!

Sunday, April 25, 2021

Nomadland

Some Confucian wisdom found its way to the Oscars this year. Chloé Zhao, who won Best Director for "Nomadland," quoted from the 13th century 三字經 / Three Character Classic she memorized as a child:

Saturday, April 24, 2021

Friday, April 23, 2021

Mandala-dimensional

Had the pleasure today of seeing a fab exhibition at the Rubin Museum of Art with a friend who hasn't been to a museum - or to New York City - in a year! Since the exhibition, "Awaken: A Tibetan Buddhist Journey Toward Enlightenment," is about expanding one's perception, it was especially trippy. The exhibition begins with this fantastic (and wall-filling) work by Tsherin Sherpa, "Luxation 1" (2016), painted in response to the 2015 Nepal earthquake but here an invitation to recognize how jumbled our consciousness is. The exhibition, originally from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, was designed before the pandemic but for its Rubin iteration someone's put together, facing Sherpa's work, a wall of pad- and phone-sized screens busily flashing a sequence of images from the past year, in case we needed reminding!

The deity here, Vajrabhairava, a wrathful manifestation of Mañjushri, is the star of this show, which we discover is patterned after the meditation journey to which a 300 century old Mandala of Vajrabhairava (above) invites you. Of course what a mandala invites you to do is to visualize in three dimensions what it presents in two (and eventually to visualize yourself as the deities you've three-dimensionally visualized: nonduality realized). The exhibition manages to make this real in quite astounding ways you need to experience yourself. (It's open through early next year.) Ritual implements made from human skulls reinforce the reality of what Vajrabhairava is doing with two of his 34 hands: grinding up someone's brains in a bowl made of the top of (someone else's?) skull. Behold: a 15th century Tibetan "flaying knife-chopper" and 19th century Mongolian "skull cup":

(You can see the hands at work in the 3rd row, 2nd column of the Sherpa painting at the top.) It would flatten the exhibition's achievement back to two dimensions for me to show you pictures of its discoveries, not to mention undo the necessary work of journeying. But I have to say that it really was a double-taking and brain-scrambling experience - and not just for my friend who's been in two-dimensional zoom world for a year... It's like discovering the three-dimensional world - and your own three-dimensional body moving through it - for the first time. So no photos for our screen world of "Awaken"'s culminating 3D show-stoppers. But I guess I can share another painting of Sherpa's from the mid-point of the journey, the two-panel 2013 "Multiple Protector (Peach)." This controlled generative whirl is what is happening to your senses as you move through the plays of light and darkness, the straight and curved walls - maybe the edges of Vajrabhairava's flaying knife-chopper in our own brains! - of this expertly mandalically-designed exhibition!

Thursday, April 22, 2021

Earth Day

Don’t Bother the Earth Spirit

Don’t bother the earth spirit who lives here. She is working on a story. It is the oldest story in the world and it is delicate, changing. If she sees you watching she will invite you in for coffee, give you warm bread, and you will be obligated to stay and listen. But this is no ordinary story. You will have to endure earthquakes, lightning, the deaths of all those you love, the most blinding beauty. It’s a story so compelling you may never want to leave; this is how she traps you. See that stone finger over there? That is the only one who ever escaped.

Wednesday, April 21, 2021

Black Lives Matter

A day after the announcement of the verdict in the trial of Derek Chauvin - guilty on all counts - a welter of feelings. It began with a confusion of tears. It is a good thing that justice was served, but not that justice was necessary. That there was any doubt at what the outcome would be - how apprehensive we all were - shows how suspicious we have become of our institutions; relief that the system can work gives way to gloomy awareness of how often it doesn't.

A day after the announcement of the verdict in the trial of Derek Chauvin - guilty on all counts - a welter of feelings. It began with a confusion of tears. It is a good thing that justice was served, but not that justice was necessary. That there was any doubt at what the outcome would be - how apprehensive we all were - shows how suspicious we have become of our institutions; relief that the system can work gives way to gloomy awareness of how often it doesn't.

Yet George Floyd remains dead, his family bereft. Most other victims of police brutality get even less than this, of course; their killers are unpunished and often the victims are blamed for their own deaths.

My second thought, after relief and a kind of delirious joy at the announcement, was "who's next? those responsible for Sandra Bland's death? Philando Castile's? Breonna Taylor's? Daunte Wright's?..." We know too many names, though we don't know nearly enough of them, and it strains credulity to imagine there will be justice for all or even many of them. Let's work and hope for it anyway, and for more. Retributive justice by itself is still part of an unjust system.

Tuesday, April 20, 2021

Monday, April 19, 2021

Exhaustion

A friend of mine at another university, finding the energy among the students in one of her classes flagging, invited them to share how they were feeling. These are anonymous virtual post-its, and I'm sure almost any class in the country - in the world - right now might generate similar expressions of shame and guilt given an instructor compassionate to inquire. We're all worn out, on many levels, but her students, like mine and many others, are also struggling with all this through screens in their childhood bedrooms or parents' basement. My friend remarked: isolation from peer groups means that many students don't have school social groups to talk to, which helps to contextualize and collectivize their feelings. Many of them are taking in the exhaustion as an individual failure. Seeing each other's distress may have helped here! How compassionate we need to be to each other in this pandemic time, and how much we still cannot fix.

A friend of mine at another university, finding the energy among the students in one of her classes flagging, invited them to share how they were feeling. These are anonymous virtual post-its, and I'm sure almost any class in the country - in the world - right now might generate similar expressions of shame and guilt given an instructor compassionate to inquire. We're all worn out, on many levels, but her students, like mine and many others, are also struggling with all this through screens in their childhood bedrooms or parents' basement. My friend remarked: isolation from peer groups means that many students don't have school social groups to talk to, which helps to contextualize and collectivize their feelings. Many of them are taking in the exhaustion as an individual failure. Seeing each other's distress may have helped here! How compassionate we need to be to each other in this pandemic time, and how much we still cannot fix.

Sunday, April 18, 2021

我第五千五百篇的博客文章

Saturday, April 17, 2021

Three million souls lost

Since I'm in a wealthy vaccine-producing country, every conversation I have these days is about vaccines - who's how far along, side effects, when they'll be fully covered, travel, what to do about those unwilling to vaccinate, what life will look like when and where "herd immunity" is reached. (I realize I've posted about it only once in over a month - for my vaccination!) The US government's pause on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine has added anxieties (for one of my students, who'd taken it two days before the announcement, it was occasion for terror), but one feels on a road to recovery. Not so other parts of the world, many of which are suffering from new waves and new variants, vaccine shortages, exhaustion and protest. It seems naive to suppose the US, too, won't be hit by a new wave... Indeed, as hospitals reach capacity across the land, the situation remains perilous here, too. NYC, over the latest hump, remains at "very high risk" of exposure.

Since I'm in a wealthy vaccine-producing country, every conversation I have these days is about vaccines - who's how far along, side effects, when they'll be fully covered, travel, what to do about those unwilling to vaccinate, what life will look like when and where "herd immunity" is reached. (I realize I've posted about it only once in over a month - for my vaccination!) The US government's pause on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine has added anxieties (for one of my students, who'd taken it two days before the announcement, it was occasion for terror), but one feels on a road to recovery. Not so other parts of the world, many of which are suffering from new waves and new variants, vaccine shortages, exhaustion and protest. It seems naive to suppose the US, too, won't be hit by a new wave... Indeed, as hospitals reach capacity across the land, the situation remains perilous here, too. NYC, over the latest hump, remains at "very high risk" of exposure.

Friday, April 16, 2021

Wari

Thursday, April 15, 2021

Wednesday, April 14, 2021

I hope you dance

In revising the syllabus for "After Religion" at mid-semester I decided to add a week on "nature spirituality." It took the place of an envisioned discussion of "religious fictions" which would have looked at books like Left Behind and The Shack, televised Mahabharatas in India, Journey to the West movies, and the various imaginings of the afterlife in Pixar movies. These would have been fun, too, but, given students' interests (as I've been able to glean them through the double-filter of zoom and lecture distance) it seemed more important to address the frontiers of spirituality beyond inherited religious traditions, rather than creativity within them.

In revising the syllabus for "After Religion" at mid-semester I decided to add a week on "nature spirituality." It took the place of an envisioned discussion of "religious fictions" which would have looked at books like Left Behind and The Shack, televised Mahabharatas in India, Journey to the West movies, and the various imaginings of the afterlife in Pixar movies. These would have been fun, too, but, given students' interests (as I've been able to glean them through the double-filter of zoom and lecture distance) it seemed more important to address the frontiers of spirituality beyond inherited religious traditions, rather than creativity within them.

"Nature spirituality" is an awkward phrase. I found it in the title of Bron Taylor's Dark Green Religion: Nature Religion and the Planetary Future (2009), a book which argued that we're witnessing the appearance of a new religion based in experiences of the sacredness of nature. (I gave students a radio interview about the book to listen to.) The force behind the International Society for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture and editor of the landmark Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, Taylor draws on fieldwork with radical environmentalists, official and off-the-record reports from scientists, surfers, the spirituality of Disney movies and much else, with special attention to Thoreau and Darwin. He sees "Animist" and "Gaian" forms of this new religion, each appearing in a "spiritual" form (believing in otherworldly, divine, supernatural intelligences), and a "naturalistic" form (which finds enough in what the senses and the natural sciences offer us). Taylor's sympathies lie with the naturalistic, which he thinks will prevail as more people discover the spiritual sustenance offered by them - who needs the word of ancient seers and exalted gurus when you can taste and see the sacred for yourself?

As I thought about other things I might want students to taste - the subject is at least as vast as Taylor's 2000-page Encyclopedia - I decided to talk about "religious naturalism," especially as articulated by Carol Wayne White in conversation with emergence theory and African American history. But as I pondered emergence I decided it might also be fun to spend a little time on the question if we are "religious by nature," a question I provocatively put this way: "Were we religious before we were human?" It's a trippy question.

While a highlight would be the delirious argument of Ursula Goodenough and Terrence Deacon (among the sources Carol Wayne White discusses) that the elements of most of our religious inklings are shared with other life forms, many quite widely, I felt I had also to introduce discussions about the spirituality some have claimed to witness in our closest kin. So we watched chimpanzees at Gombe and Jane Goodall's assertion that their unusual behavior around a waterfall must be expressions of "awe and wonder."

While a highlight would be the delirious argument of Ursula Goodenough and Terrence Deacon (among the sources Carol Wayne White discusses) that the elements of most of our religious inklings are shared with other life forms, many quite widely, I felt I had also to introduce discussions about the spirituality some have claimed to witness in our closest kin. So we watched chimpanzees at Gombe and Jane Goodall's assertion that their unusual behavior around a waterfall must be expressions of "awe and wonder." Tuesday, April 13, 2021

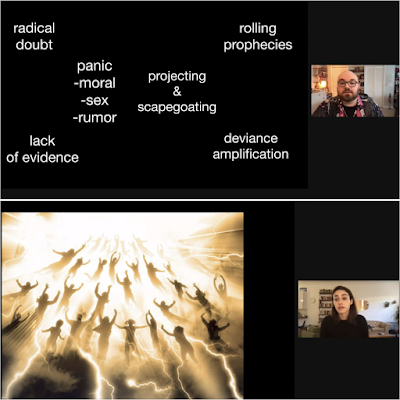

Left behind

Learned a heap at today's Religious Studies Roundtable on QAnon and Religion - including how odd our methodo-logical agnosticism ("we're not discussing whether this is true or false") sounds outside the familiar contexts. Well done, students!

Monday, April 12, 2021

Festive

This week our college is celebrating the work of our intrepid students, who have continued, despite pandemic and zoom quarantine, to do remarkable things. Religious Studies is a comparatively tiny program but is well represented. The poster session of today's Dean's Honor Symposium included three projects which grew out of our classes - Mia Perez's "Seminarium: Literary Mysticism and Us" and Skye Telleen's "Jesus as Mother," inspired by the course "Meetings with Remarkable Mystics," and Kate Zibluk's "Cyclical Scripture," which began as a final project for "Performing the Problem of Suffering: The Book of Job and the Arts." And tomorrow our Spring Roundtable will feature the work of two graduating seniors, Elliott Ryan and Stephanie Zamarripa, whose capstone research projects afford them special insights into the unnerving phenomenon of "QAnon and Religion." Congrats!

This week our college is celebrating the work of our intrepid students, who have continued, despite pandemic and zoom quarantine, to do remarkable things. Religious Studies is a comparatively tiny program but is well represented. The poster session of today's Dean's Honor Symposium included three projects which grew out of our classes - Mia Perez's "Seminarium: Literary Mysticism and Us" and Skye Telleen's "Jesus as Mother," inspired by the course "Meetings with Remarkable Mystics," and Kate Zibluk's "Cyclical Scripture," which began as a final project for "Performing the Problem of Suffering: The Book of Job and the Arts." And tomorrow our Spring Roundtable will feature the work of two graduating seniors, Elliott Ryan and Stephanie Zamarripa, whose capstone research projects afford them special insights into the unnerving phenomenon of "QAnon and Religion." Congrats!

Saturday, April 10, 2021

満開

Friday, April 09, 2021

Animating ideas

No wonder! No wonder that our sophisticated civilizations, brimming with the accumulated knowledge of so many traditions, continue to flatten and dismember every part of the breathing earth … For we have written all of these wisdoms down on the page, effectively divorcing these many teachings from the living land that once held and embodied these teachings. Once inscribed on the page, all this wisdom seemed to have an exclusively human provenance. Illumination—once offered by the moon’s dance in and out of the clouds, or by the dazzle of the sunlight on the wind-rippled surface of mountain tarn—was now set down in an unchanging form. [281]

Stengers notes that "Abram still writes and passionately so," but not as a critique. Might there be a way of understanding "writing (not writing down) [a]s marked by the same kind of crucial indeterminacy as the dancing moon"? It's a beautiful, if poignant move, and one which thrills me as someone ambivalent about what she's calling "writing down." She proposes a magical way of describing what happens when a person writes.

Writing is an experience of metamorphic transformation. It makes one feel that ideas are not the author’s, that they demand some kind of cerebral—that is, bodily—contortion that defeats any preformed intention.

What I take her to mean (with a bright array of provisos, of course!) is that the craft of writing, from the perspective of the person doing it, is one of tangling with things felt to be beyond the writer, which the writer is trying to do right by in words. Later it will seem that these were "my" thoughts all along, but at the moment of writing, they aspire to something more and different, something beyond and separate from me. But where Abram illuminates the way speech participates in the always local and always more-than-human world of change and relationship and breath and feeling, Stengers is thinking about writing, and ideas. She references Whitehead's famous claim that western philosophy is just "footnotes to Plato" and gives it a little spin: something in Plato's ideas (not to mention Plato's Ideas) invites footnotes. As we philosophize, as we write, ideas animate us.

Writing, Stengers proposes, is really also a kind of animism - a recognition that we are enmeshed in relationship with other than human agencies. Properly understanding it might help us

recovering the capacity to honor experience, any experience we care for, as "not ours" but rather as "animating" us, making us witness to what is not us.

But she shares Abram's worry about the way the written word estranges us from the world by making the abstracted seem the really real. Can writing be recovered as an animistic practice? Perhaps if we focus on it as craft, as magic - terms she recovers in this essay. Or, since she is a philosopher for science after all, as akin to what she calls the "adventures of science." Unlike "Science," which is thought to be the only and ultimate arbiter of what's real, inevitably disenchanting the world (but doing so only because we think that's what it does), Stengers celebrates a little-s science as local as Abram's orality.

An experimental achievement may be characterized as the creation of a situation enabling what the scientists question to put their questions at risk, to make the difference between relevant questions and unilaterally imposed ones. [¶] What experimental scientists call objectivity thus depends on a very particular creative art, and a very selective one, because it means that what is addressed must be successfully enrolled as a “partner” in a very unusual and entangled relation.

Scientific experiments yield knowledge when they allow the things beyond our ken to animate our interactions with them, but the knowledge lives only when understood as localized in particular experimental situations (milieux). Knowledge grows as these situations proliferate rhizomatically, engaging creatively with other partners in other locations. It stops growing when this is forgotten, becoming instead a barrier to the reality of our constant partnering with the other than human. That's why we need to retrieve words like magic, especially in the now largely metaphorical sense in which we speak oof "magical" events, landscapes, etc.

Protected by the metaphor, we may then express the experience of an agency that does not belong to us even if it includes us, but an “us” as it is lured into feeling.The metaphor may be enough to recover a sense of an un-disenchanted world. Stengers imagines neopagan goddess worshipers bemused by the blinders the deadening categories of a "Science" which thinks it has vanquished animism forces on us:

If we said to them, "But your Goddess is only a fiction," they would doubtless smile and ask us whether we are Mong those who believe that fiction is powerless.

Though I am simply enraptured by how Stengers uses "believe" here, the words she writes down aren't on the whole words I am comfortable handling. Where I'm talking relationships and persons (terms from animism as some others define it), she uses the language of rhizomatic assemblages from Deleuze and Guattari, ensembles of constantly reconstituting relations where even the idea of individual agency dissolves, not to mention persons. For her the animistic experience of writing is ultimately one where the assemblage writes. She's a "partner" in the writing just like the ideas and everything else.

my existence is my very participation in assemblages, because I am not the same person when I write as I am when I wonder about the efficacy of the text after it is written down.This is a philosophical animism I can't quite follow - or should I say that no assemblage yet has me following it? But I've enjoyed trying to write about it, that is, letting it animate me. I'm not sure I could manage this for a less obviously "localized" craft of writing than this blog, but maybe that proves her point. Here I don't have to be the same person, or carry out the same intention, from day to day. I largely punt on the question of "the efficacy of the text after it is written down," and this allows me to craft it in the first place.

But enough about me. This intricate and illuminating argument from Stengers helps me appreciate what she will later mean by the "intrusion of Gaia," too. For Gaia represents an Earth no longer willing to partner with us, a frustrated animism:

Gaia is the name of an unprecedented or forgotten form of transcendence: a transcendence deprived of the noble qualities that would allow it to be invoked as an arbiter, guarantor, or resource; a ticklish assemblage of forces that are indifferent to our reasons and our projects.Thursday, April 08, 2021

Unsafe

Can one understand another person's fear? Today I realized I've been failing even where I thought I was doing okay. After a long zoom conversation with a colleague who hails from China, touching on anti-Asian violence and the insufficiency of the responses of various bodies, where I proudly recounted switching my classes online a week earlier than everyone else last year because Chinese students told me they didn't feel safe coming to school, I cheerfully said "once things settle down, let's try to get together, over food!" It fell to her to say she wasn't sure when she'd feel safe taking the subway again. How could I be so thoughtless? We'd just been talking about how folks didn't take seriously the fear Asians feel even going out these days. Indeed we'd both reported we couldn't unsee the video of an Asian person being beaten to unconsciousness in the New York subway a few weeks ago, while other passengers did nothing. Didn't I post that New Yorker cover which shows how the subway has become a place of unease and even menace everywhere I could? And yet I blithely assumed the subway is generally safe, the subway where Asians are assaulted and other passengers may do nothing to help.

I think I've learned to sense a little of the fear women feel walking on dark, empty streets at night - or that this is a frightening situation. But while I know it I don't feel that particular threat there. (There are places where, as a gay person, I feel unsafe, though not as many as if I presented differently.) Likewise, although particular cops may seem unsavory to me, I don't feel unsafe around the police in this country, as African Americans must. Indeed, I feel safe because I assume the police would come to my aid were someone to accost me. I remember well an episode Ta-Nehisi Coates described in Between the World and Me where a white woman says to him, in an Upper West Side movie theater, "I could have you arrested." I know I could, too.

I guess the fear Asians and Asian Americans have been feeling on the streets, in the subways, in shops and restaurants isn't one I really feel either. I can't picture their assailants - they seem to come from a world I can barely conceive, both in their prejudices and in their acting them out against vulnerable people - but I haven't had to live with constant micro aggressions, coming from all sorts of people, including people like me. I've not been told, verbally and nonverbally, that I don't belong in my own country, or the supposed "land of immigrants" to which I've come for study or work or family - that I never can. While I've read about it - most only in the last weeks, especially on the intersectionality of Asian women's experience in America - and idly wondered about the experiences of Asian Americans of various generations as the US becomes more visibly diverse, I've never felt racially invisible in that way, and, now, racially unsafe. White folks get to not feel racially anything, even as everyone else does.

My colleague had spoken about the great and unacknowledged mental suffering of AAPI students she speaks to. The context of people coming from China, like a significant number of the students at my university, is more complicated still. To thoughtless stereotypes of model minority and perpetual foreigner add geopolitical rival and disease vector (things I'm probably naive to imagine less common at a university like our own), and - unashamedly present at universities including our own - cash cow. You know: like so many schools, we depend on the full fee tuition of presumably well-off foreign students to get by. How does the way we talk about that feel to these students (or those the racist gaze equates with them)? For our university, as for our land, it must sound like they're not part of the narrative at all, at best tolerated if noticed at all, their indignities unmourned. I need to do better.