In "Religion and Ecology" we read an essay by John Daido Loori about Dogen's "Mountins and Waters Sutra," but what really got to students was a scratchy old film he'd shot, called "Water speaking water." (There are longer versions.) It was made among the streams flowing into Raquette Lake, near one of whose shores we are staying. Here's the lake sharing late in the day enlightenment. There are mountains hidden in water!

In "Religion and Ecology" we read an essay by John Daido Loori about Dogen's "Mountins and Waters Sutra," but what really got to students was a scratchy old film he'd shot, called "Water speaking water." (There are longer versions.) It was made among the streams flowing into Raquette Lake, near one of whose shores we are staying. Here's the lake sharing late in the day enlightenment. There are mountains hidden in water!

Monday, May 12, 2025

Rippled

Tuesday, May 06, 2025

Greening of the self

Tuesday, April 22, 2025

Forest rain and forest fires

One of the final sessions of "Religion and Ecology: Buddhist Perspectives" almost became a religion ot trees class today. I'd chosen three final readings from the old anthology Dharma Rain: Sources of Buddhist Environmentalism - the passage from the Lotus Sutra which gave the anthology its name, an essay on "the religion of consumerism" from Sulak Sivaraksa's 1991 Seeds of Peace: A Buddhist Vision for Renewing Society and Gary Snyder's semi-serious "Smokey the Bear Sutra" of 1969.

The "Medicinal Herbs" fascicle of the Lotus Sutra argues that the limitless Dharma, like a soaking rain which lets each and every kind of plant thrive, naturally expresses itself in a variety of teachings suitable to the variety of suffering beings. I was hoping that would allow us to sense a wide and still unfolding tradition in Sivaraksa's critique of consumerism in Thailand as well as Snyder's revelation of Smokey the Bear as a kind of Dharma protector for Americans.

Discussion of the Lotus section went well enough. A student from Pakistan helped us appreciate the text as written in a monsoon climate, to which I added that the "inferior, middling and superior" medicinal herbs and small and large trees to which the Lotus likens beings of different levels of enlightenment should be understood as constituting a forest, each part of which was distinct and necessary - herb, understory, canopy. Even the tallest trees can't provide the healing of ground-hugging medicinal herbs, though they provide shade for them. So far so good. The "Dharma rain" wasn't just offering each individual something that worked for them, but sustained a whole interconnected world.

But if religion and trees was helping here, students weren't having it come Smokey. Zen poet Snyder revalues the familiar U. S. Forest Service mascot, whom the Buddha "once in the Jurassic about 150 million years ago" announced would be his "true form" in our time:

... Bearing in his right paw the Shovel that digs to the truth beneath appearances, cuts the roots of useless attachments, and flings damp sand on the fires of greed and war;

His left paw in the mudra of Comradely Display—indicating that all creatures have the full right to live to their limits and that deer, rabbits, chipmunks, snakes, dandelions and lizards all grow in the realm of the Dharma;

Wearing the blue work overalls symbolic of slaves and laborers, the countless men oppressed by a civilization that claims to save but often destroys; ...

Trampling underfoot wasteful freeways and needless suburbs, smashing the worms of capitalism and totalitarianism...

Fun, huh? The students tasked with leading the discussion on this weren't having it. "We all hate Smokey the Bear!" they cried. Why? He's so commercialized! He represents the settler colonial effacement of indigenous peoples! He's the emblem of the fire suppression strategies which generate mega fires! He anthropo-morphizes the non-human world! The real Smokey bear cub was rescued from a fire only to spend the rest of his life in a cage! He makes tourists endanger themselves thinking real bears are warm and cuddly!

Did you read beyond the title, I asked? Snyder isn't actually much more interested in forests than the Lotus Sutra is. It's a metaphor, a skilful means... They assured me they hated Snyder too, whom we've critiqued for claiming he had become a "Native American." When I observed that Synder was one of the models for Kerouac's Dharma Bums one volunteered "I hate the Beatniks!"

This conflagration of Smokeyphobia caught me by surprise. Synder's "Sutra" is celebrated among American Buddhists, appearing in the HDS "Buddhism through its Scriptures" MOOC as well as the Norton Anthology of World Religions, not to mention Dharma Rain. But clearly what was a skilful means for older generations wasn't working for these students.

I tried to let this be the takeaway of our discussion. Smokey's clearly not the medicine we need now. But the forest is full of plants. "What might a more skillful metaphor be?" Our class time had sadly run out. But I think we were all struck by the ferocity of the reaction to the "Smokey the Bear Sutra." That must be telling us something. Perhaps it's the effrontery of the generations which destroyed the environment telling children "Only YOU can prevent forest fires." On Earth Day no less!

Tuesday, March 25, 2025

Unmet need

"Religion and Ecology" had a field trip to the Met today, to see "Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature" and take a stroll through the Asian art wing looking for Buddhist works, but, as often happens, many students weren't able to come. The museum is too far from school for students with classes immediately before and after ours to be able get there and back. I'd asked those whose schedule didn't allow going today to go on their own time, and everyone to share a few pictures with some thoughts online, but many probably won't go. How to make them want to? Here are the pictures, with comments, which I posted...

I found myself going back and back to this early ink painting of Friedrich's - this is the lower right corner. I don't know how he manages to convey misty moonrise light so well...

Seeing this famous painting, familiar from many a book cover, in the context of Friedrich's other works, was quite revealing. In no other work is the human form so large or dominant. The human is lost or exalted or absorbed in nature in most of the others... making this a most unrepresentative work of his!

I think Friedrich's landscapes pulse with sentience, especially when uncluttered by explicitly Christian symbols! "Bushes in the snow (From the Dresden Heath II)" is one of a pair which flummoxed viewers when originally displayed for the depicted trees' unremarkableness, and one an otherwise enthusiastic reviewer of this exhibition found uncanny and threatening. Is nature so inhuman?

In Friedrich's painting of the Alpine peak "The Watzmann" (this is a detail), he's put the mountains he knows and loves in the foreground, with the mountain peak Friedrich never saw (but a friend had sketched for him) in the background. I'm charmed by his familiar trees, and intrigued by the intermediate mountain he conjures up...

The different meanings people projected onto this painting are fascinating. Is the forest friendly or, as some of the nationalistic interpretations after the defeat of Napoleon imagined, hostile, even murderous - at least toward invading Frenchmen?!

This is another wonder of atmosphere. It looks misty but if you get close, every detail of the tree's branches is there - as if you'd approached it through a fog.

This is also my favorite of his explicitly Christian works, perhaps because the crucifix is not facing us but looks away into the distance...

This 14th century painting of Kannon (Avalokitesvara) in the Japanese collections is one of the few Buddhist works with natural details beyond the figures of enlightened anthropomorphic beings...

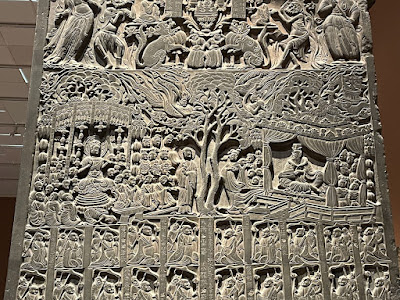

Closeup of the 6th century Chinese stele in that first hall of Chinese art, with glorious animated trees (which reminded me of Friedrich's "Bushes in the Snow" above). Or maybe it's a single double-stemmed tree, relating to the story of how the (male) disciple Sariputra took the form of a woman - that's them on both sides of the tree(s)!...

It's worth going to the Caspar David Friedrich exhibition just to see this amazing painting. This isn't all of it, but registers my surprised discovery that the human figure, perhaps a monk, is not alone before the sublimity of sea and storm and sky, but is kept company by birds.

Doesn't this make you want to go too, for a closer look of your own?

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Myriad nature

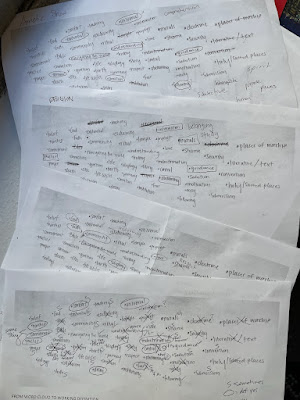

The torrent of words our class free-associated with "ecology" on Tuesday furnished the platform for today's discussion of the promise of religious naturalism. I'm always warning against the false closure offered by definitions, and often solicit such whiteboards full of terms from students, parsing what we come up with together for richer, perhaps conflicting understandings hidden behind apparently self-explanatory terms. These give a sense of finality, too, though - many students take pictures of the sprawl on the board, but I'd be surprised if anyone ever looked at them again.

I'm trying to do more with them "Religion and Ecology." A few weeks ago, we generated a spray of words around "religion" initially strikingly unconnected by the texts we'd been discussing at the end of one class, and in the next I had students read through them again and select among them to write out working definitions of their own.

This time, I also reproduced the word cloud on a handout. The instructions were to go through the whole list and circle each word which seemed applicable to "nature," and then go through them all again and underline each which seemed to relate to "human." It was an attempt to shoot the moon on the self-defeating question "what is the human relationship to nature?" - self-defeating because the very formulation presents the two as unrelated, separable. This proved a little unwieldy in practice - despite my instructions most went through weighing each word for leaning one way or the other - but it led to a fruitful discussion. Shouldn't every underlined word also have been circled? Some of the more negative, or more conceptual things seemed to some students only "human," but aren't we part of nature? And if so, aren't even our most irritating and ecologically destructive traits natural? This seems obviously true in general but sticks in the craw when you have to make it particular through all these terms.

Students kept wanting to absolve nature of responsibility through claims that "only humans" were one way or the other, at first negative but then more general: self-aware, language-using, tool-using, aware of death, cultural... I pushed back each time, pointing to recent findings in animal and even plant studies and then asking, again and again, "does it matter if it's not only us?"

Religious naturalism is in one sense the view that everything human is, of course, natural, and so, of course, must the world of our religions be. Even the most elaborate conceptions of a supernatural reality are natural phenomena! My accounts of religious naturalism usually stop there. (It's plenty!) But in the context of today's evocation of the wisdom and play, the grieving and language, the art and awareness of our other-than-human kin, I experienced in a new way what might count as religious about this view. Are not religious feelings like awe, wonder, humility, participation, gratitude ... appropriate responses to it?

What about vocation? We may not be the only ones to be/do XYZ; put differently, there may be more than the human way of being/doing XYZ. Thinking we should be defined by what we alone are or can do replicates the biblical idea that we are not part of nature but made in the image of something beyond it. (There are analogs in other traditions.) But even if there were things exclusive to us, why should they be the most important thing about us? What if we understood our ways of being and doing as part of the unfolding creativity of what Carol Wayne White calls "myriad nature"? What if we were and did them with this understanding, one voice in a glorious cosmic chorus?

But today was also a Thursday, and since this iteration of "Religion and Ecology" focuses on "Buddhist perspectives," that means we ended with a meditation. Today's was a "metta" meditation led by Sharon Salzberg, which quietly widens the circle of care (may ___ be free from danger, ... be happy, ... be healthy, ...live with ease) from the self to humans known and less well known and then to "all beings." At the end I invited the students to flip over our handout and spend five minutes writing whatever came to mind. The concentrated silence was lovely.

When we gather again next week we'll see what this all added up to.

Tuesday, February 25, 2025

Tuesday, February 18, 2025

Process this!

I've tasked students in "Religion and Ecology" to kick off each Tuesday class session with an account of what we got up the week before. They work in pairs, and each presentation has a different way of summarizing and synthesizing. Today's presenters organized their thoughts on something called a Miro board (which was a little larger than this when projects but not enough to read the text), coding our different texts by color. The purple and orange boxes are labeled "process" and the light blue box at far tight was our group walking meditation.

Friday, February 14, 2025

Timing

It would be a busy semester even without the carnage of the old-new presidential regime, tearing at the foundations of our world. But somehow I'm managing to keep things on track, generating welcoming learning communities in which students are making friends and engaging challenging ideas - part of "carrying on" as resistance to chaos and paralysis. As I stagger to the end of the week I'm particularly pleased with the way I was able to end the last two.

The week had started with reading some classic texts in "Religion and Ecology": Lynn White's field-creating 1967 essay on the religious origins of the ecological crisis, and one of the texts he refers to, the creation narrative in Genesis 1 - home of the "dominion clause" which, White argues, in western Christianity formed the uniquely anthropocentric civilization despoiling our planet.

Then, in "After Religion," came the travails of secularism, an embattled ideal in need of challenging and perhaps also championing. Heady stuff; I might share some of the class's ideas with you next week.

Let me say a little more about the second session of "Religion and Ecology." Following up on Genesis 1 we read the alternate (actually older) creation narrative of Genesis 2, then contrasted both with the cosmology of the Skywoman story with which Robin Wall Kimmerer starts Braiding Sweetgrass. Despite glaring differences, there was no relation - let along community - recognized among the human and other than human in either Genesis. Then we rubbed it in more with a reading of Genesis 3 - the banishment from Eden - and a reread of Kimmerer's words about the fateful encounter of the "offspring of Skywoman and the children of Eve," which we read two weeks ago.

On one side of the world were people whose relationship with the living world was shaped by Skywoman, who created a garden for the well-being of all. On the other side was another woman with a garden and a tree. But for tasting its fruit, she was banished from the garden and the gates clanged shut behind her. That mother of men was made to wander in the wilderness and earn her bread by the sweat of her brow, not by filling her mouth with the sweet juicy fruits that bend the branches low. In order to eat, she was instructed to subdue the wilderness into which she was cast.

Same species, same earth, different stories. Like Creation stories everywhere, cosmologies are a source of identity and orientation to the world. They tell us who we are. We are inevitably shaped by them no matter how distant they may be from our consciousness. One story leads to the generous embrace of the living world, the other to banishment. One woman is our ancestral gardener, a cocreator of the good green world that would be the home of her descendants. The other was an exile, just passing through an alien world on a rough road to her real home in heaven.

We'd read this together before; now we get it, the class said! We turned then to Kimmerer's "grammar of animacy," the urgent need to learn to recognize all the other than human peoples around us, who offer us wisdom and relation - which might start with the use of a new pronoun, ki.

All of this, amazingly, we did in 75 minutes, and class is 100. For the balance of class I led the group in a Thich Nhat Hanh-inspired silent group walking meditation around the block. I'd promised them both a field trip and meditation, and this wasn't what they were expecting, so I thought I might as well throw ki into it too. Mind your walking slo-o-o-owly, I said, and connect with the other than human kin along the way. We'll take 20 minutes, and I'll make sure we finish on time by setting my timer for 15 minutes: you can silence your phones. At 15 minutes the class had settled a little restlessly into the ultra-slow pace I'd set (from the rear) and we'd reached only halfway around the block! It felt like crazy speeding up returning to the normal pace which delivered us back at school at exactly 3:40. That was amazing, said one student, perhaps a little insincerely. The amazing thing, I responded, is that you could do this around any block, any time.

I stuck the landing for the James' Varieties class today, too. We had a friendly and wide-ranging discussion of the "sick soul," and the profound sense of the cruelty and meaninglessness of the world which James argues some of these "religious pessimist" are "congenitally fated" to dwell on. This class professes to be more "healthy-minded" than others I've guided through this book, and many thought the agonies of the sick souls overwrought. "Don't ruin it for it for everyone," responded one in half-jest to Tolstoy's account of the bottom falling out of his outwardly successful life.

But James wants us to face the fact that anyone's life could come unmoored due to forces beyond our control. So in the class' last minutes I had someone read aloud the text James put in a footnote to the chapter's final paragraph, a terrifying account of a group walking at night (presumably in India) whose leader was suddenly dragged away by a tiger. The rush of the animal, and the crush of the poor victim's bones in his mouth, and his last cry of distress, ‘Ho hai!’ involuntarily reëchoed by all of us, was over in three seconds. The shell-shocked survivors found themselves on the ground, we heard, initially unable to move for fright, and only a whisper of the same ‘Ho hai!’ was heard from us. Eventually, still stunned, they were able to sprint to safety, but were surely tiger-haunted for the rest of their days. How's that for the precarity of good fortune?

Class was in its final minute. "Ho hai," I said. "See you next week."

I'm pleased with the elegance of these class endings, but really I'm happy that in this fourth week of the semester the class communities feel like they have become enough of a reality that I can throw such disconcerting things at them in parting. They know we'll be together again next week. And, I hope, they feel - from the precise timing of the class finales - that I can be trusted to keep these spaces safe for abiding with the big, hard questions together.

Thursday, February 06, 2025

Cloud of knowing

Came up with a fun new twist on the "what is religion?" brainstorm cloud. At the end of last class, students coughed up terms you might use in a definition, generously written on the whiteboard by another student as one word sparked another, and another, and... Students often take a picture of the word cloud as if it were something final or complete. This time I took a picture and printed out for the class' next session, with a task: circle six terms, cross six more out, add up to three, and then come up with a working definition.

Tuesday, January 28, 2025

Beyond AI

I used AI in class today.

The class was "Religion and Ecology: Buddhist Perspectives," and it became clear last week that many had signed up for the class for the "Buddhist" part but brought no prior knowledge of it. "Would you like me to give a short introduction to Buddhism next week," I foolishly asked, and of course the answer was yes. I've done similar things in years past, always queasy at the simplifications, but students need some overview of this vast tradition, if only to appreciate its vastness.

But then came the faculty retreat on AI, where we were encouraged to experiment with AI in connection with what we were teaching, so I asked first one, then a second, AI engine for three ways to give a 45-minute introduction to Buddhism. They were impressive - historical, thematic, with an activity, etc. - but the content for all was pretty much the same. I couldn't get any of them to offer me any hint that there might be more than one way to tell the story.

So that was my story in class! I told the class I'd gone AI foraging (some eyebrows lifted a little), and they'd all recommended the same story, which I would describe to them but then show why they were lucky to have me by showing the story's limits.

What the AIs all recommended was spending the majority of the time on the life of Siddhartha Gautama and the story of his enlightenment, along with the most celebrated of his teachings: the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path and, perhaps, non-self, interdependence, meditation, etc.. After that they counseled wrapping up with a few minutes on the spread of Buddhism (Theravada, Mahayana, Vajrayana), and a final few minutes on Buddhism today. I zoomed through that in ten minutes, availing myself of a projected map of Asia to draw arrows pointing to central, east and southeast Asia. If they wanted more on any of this, I could recommend AIs they could consult.

And yet there were some big problems with this story. For a 2500 year old tradition spread across an amazing range of cultures and languages, generating new texts as it went, how could it be right to spend only 5-10 minutes out of 45 on that spread? Practices, ideas, iconography varied so much in each of these places and at different times - interacting with indigenous and other teachings and communities all along the way - that many scholars think it more helpful to talk about Himalayan religions, religions of Southeast Asia, Chinese religions, etc than a pan-Asian 'Buddhism.' Such local emphasis could counterbalance the implication of the Gautama-heavy story that what happened over those 2500 years was at best faithful transmission, and, if things differed, a drift away from purity or authenticity. But it's in the nature of traditions to grow and change.

Further, I averred, few of the people who lived in all of those places and times (and remember that Buddhism disappeared from its native India) would recognize the AI-endorsed story as their own. Look at any of their temples: they're full of statues but almost none of them are of Gautama. Since he was just one of many beings enlightened to the same truth, his biography is irrelevant. (And if you are interested in him you should be interested also in the stories of his 500+ earlier lives chronicled in the Jataka Tales.) The traditions are full of new teachings (and teachers), further articulations, they claim, of the same truth - with plenty of criticisms of others for failing to keep up. (These criticisms, which you'll find in any tradition, were what I sought in vain from the AIs.)

Is Buddhism not a thing, then? Not the kind of thing the AI proposed - a world religion launched into history complete by a single remarkable individual. It's a tradition, which I availed myself of Alasdair Macintyre to suggest is not all about uniformity and agreement; rather, “A tradition is an argument extended through time in which certain fundamental agreements are defined and redefined.”

What fundamental agreements? The world religions stories brought together by the AI would point to something like the problem of suffering, but that may be a problem for many traditions. What we can see as distinguishing Buddhist traditions, I suggested, is that they found the cause of suffering not in sin or chaos or human nature or a struggle between light and darkness but ignorance.

A simplification, of course. Ignorance or delusion is but one of the three poisons that produce clinging, but it fuels the other two (greed and hatred). And the dispelling of ignorance doesn't just release one from suffering but - depending on your flavor of Buddhism - discloses worlds of unimagined relation, wisdom, compassion, power and delight. Depending where and when we're talking on our map and timeline of 'Buddhism,' it would come with a different story.

All this was definitely a lot for a first overview. Too much, if this were all! But for a start I hope it'll do. Students know there's a facile view and where to find it, and why it's worth learning more.

Thank you, AI?

Thursday, January 23, 2025

Syll up!

Tuesday, January 21, 2025

Grounding religion

"Religion and Ecology: Buddhist Perspectives" kicked off today. Most of class was dedicated to a discussion of Myōe's "Letter to the Island," which turned out to be a great starter text, but before that I tried to set up what we were doing with some books. The top three are our main sources of material; I brought along Mannahatta to make the point that our thinking should be "grounded" where we are. The course gambit, expressed in the book pile: academic work, introduced in the new (2024!) edition of Grounding Religion: A Field Guide to the Study of Religion and Ecology, should be grounded in the place we are, Turtle Island, with Braiding Sweetgrass helping us learn to recognize our dependence on and obligations to the land and our non-human kin, but also watered by the Dharma-Rain of Buddhist traditions. It'll make more sense in practice!

And speaking of practice, students' first assignment is to write a "Myōe letter" of their own - personal, addressed to a nonhuman they already have a relationship with, modeled on Myōe's. In an announcement explaining the assignment, I wrote

I hope you left our discussion with a strong sense of just how weird Myōe's text is, a first taste of how challenging (and enlightening) Buddhist perspectives can be. I hope you also got an appreciation that "Buddhism" is no one thing but a vast world of ideas and practices from many times and places, often in disagreement, and often, on first reading, very weird. Myōe's letter doesn't just seem weird to us because we're reading it in English translation most of a millennium after it was written, with scant to no knowledge of its sources and context. It was meant to seem weird to the contemporaries who might read it, too. How absurd to write a letter to an island!! But is it just performative?

Your assignment, to write what I'm calling a "Myōe letter," is also very weird, indeed weird in ways you'll appreciate only when you actually sit down to write it. (I'm a firm believer in learning by doing, for pedagogical as well as Buddhist reasons. Talking about religion, especially a practice-based tradition, gives you at most the illusion of understanding it.) To be clear, I'm not asking you to be Myōe or Buddhist or Japanese or to address a Japanese island! The task is for you to write a personal letter to an island or tree or other nonhuman with whom you already have a relationship. Even if you may already hug that tree or dance your thanks to that piece of land, writing a letter is a weird thing to do, so, for the benefit of that mountain or river or whomever, include a few paragraphs, as Myōe does, articulating what an odd thing you're doing in writing the letter and why. If you find this impossible to do, find words for that too. (I can tell you about a woman who, invited to talk to a plant, tearfully apologized to the plant for not being able to speak to it.) We can talk about the assignment in class Thursday as well, but only if you've started to do it. ;)

Thursday, January 02, 2025

Keep breathing

Up again, another record year, and we know mitigation efforts will be reduced in the coming years... It's hard not be disheartened, and to harden one's heart in reaction. What can be done?

Up again, another record year, and we know mitigation efforts will be reduced in the coming years... It's hard not be disheartened, and to harden one's heart in reaction. What can be done?

I have the privilege of teaching a course on religion and ecology next semester. I haven't taught that class in five years, and more than global annual temperature has changed. We've had four years of decisive response to the climate crisis. But the class starts the day after the inauguration of the new-old president, and as he signs a sheaf of reactionary executive orders many of which will promote the climate crisis-denial shared by his gang of thugs.

This iteration of "Religion and Ecology" will explicitly engage Buddhist perspectives, and they may help us keep our hearts soft. As I've worked out the syllabus, I've made more central than in any past class how we'll be building a community through shared practices.

Monday, December 30, 2024

Mountains aren't mountains and river's aren't rivers

For a contemporary folly, here someone shows the magnitude of the world's great river systems by imagining them flowing out into space!

For a contemporary folly, here someone shows the magnitude of the world's great river systems by imagining them flowing out into space!Why am I showing these to you, you may wonder? Because one of next semester's classes is a reprise of "Religion and Ecology," which I've promised will focus on "Buddhist perspectives," most especially Dogen's "Mountains and Rivers Sutra." This has in turn reconnected me to some of the excitement of the "Sacred Mountains" course I taught eight years ago. Gray's is of course the absolute antithesis of Dogen's "mountains and rivers" but perhaps useful on our way to recognizing that mountains are not mountains, rivers not rivers, although mountains are mountains, rivers rivers!

Sunday, December 15, 2024

No man is an island

And back to California for the holidays! The movie player on the seat in front of me wasn't working so I had a chance to delve into Dharma Rain: Sources of Buddhist Environmentalism (2000) - just what I needed to start pondering my upcoming spring "Religion and Ecology" class, which I've promised will center "Buddhist perspectives." One very happy discovery, a short work by Japanese monk and visionary 明恵 Myōe (1173-1232) entitled "Letter to an Island," enacts the nonduality of animate and inanimate, Buddha and the rest, by addressing an island (conveniently if coincidentally called Karma) Myoen knows from childhood.

Dear Mr. Island, it begins, How have you been since the last time I saw you? After I returned from visiting you, I have neither received any message from you, nor have I sent any greetings to you. then swiftly moves into preaching: I think about your physical form as something tied to the world of desire, a kind of concrete manifestation, an object visible to the eye, a condition perceivable by the faculty of sight, and a substance composed of earth, air, fire, and water that can be experienced as color, smell, taste, and touch. Since the nature of physical form is identical to wisdom, there is nothing that is not enlightened. Since the nature of wisdom is identical to the underlying principle of the universe, there is no place it does not reach.

So Mr. Island isn't distant or even really an island, but assuredly a friend! After a little more learned disquisition, Myōe becomes personal again.

Even as I speak to you in this way, tears fill my eyes. Though so much time has passed since I saw you so long ago, I can never forget the memory of how much fun I had playing on your island shores. I am filled with a great longing for you in my heart, and I take no delight in passing time without having the time to see you.

And then there is the large cherry tree that I remember so fondly. There are times when I so want to send a letter to the tree to ask how it is doing, but I am afraid that people will say that I am crazy to send a letter to a tree that cannot speak. Though I think of doing it, I refrain in deference to the custom of this irrational world. But really, those who think that a letter to a tree is crazy are not our friends. ...

This would make a nice bridge from "Religion of Trees"!

Myoe, "Letter to the Island," trans. George J. Tanabe, Jr., in Dharma Rain: Sources of Buddhist Environmentalism ed. Stephanie Kaza and Kenneth Kraft (Boston and London: Shambalah, 2000), 63-65; portrait of Myōe in a tree from Kōsanji, Kyoto

Monday, May 16, 2022

Tables turned

Wednesday, May 11, 2022

Wednesday, May 04, 2022

Pirouette

Time to turn to the text, pairs tasked with choosing an important passage and writing it on the whiteboard. They made excellent choices; going through them let us experience the poetry, the sweep and the detail of Kimmerer's text weaving. We ended the class listening to an excerpt of a new podcast where Kimmerer retells the story which frames Braiding Sweetgrass, where it is called "Skywoman Falling." (It's the April 26th podcast here, starting 3 minutes in.)

Time to turn to the text, pairs tasked with choosing an important passage and writing it on the whiteboard. They made excellent choices; going through them let us experience the poetry, the sweep and the detail of Kimmerer's text weaving. We ended the class listening to an excerpt of a new podcast where Kimmerer retells the story which frames Braiding Sweetgrass, where it is called "Skywoman Falling." (It's the April 26th podcast here, starting 3 minutes in.) Why tell this part of the story now - and why not before? We concluded it had something to do with the book's argument that our world is co-created and sustained by many peoples, including us. Maybe the more recent, fuller telling speaks more to the sense of ecological cataclysm - the tree of life uprooted by a storm?! - and the importance of holding on to what we can of our disrupted world. However she comes by it, and even if it didn't save her from falling, the branch she holds introduces plants to the emergent turtle island.

Our classmates outside the window were waiting for us to put two and two together, and finally it hit us. "Skywoman falling" - the story which begins the book and which Kimmerer starts to retell at the end, fighting off despair - starts like this: She fell like a maple seed, pirouetting on an autumn breeze (3) - a whirligig. What a gift of joy!

Monday, May 02, 2022

Sitting in it

As "Religion and Ecology" wends to a close - next week is for student presentations and the final class for closing syntheses - we experience the way two of our main texts wrap things up. Wednesday we'll reach the soaring conclusion of Braiding Sweetgrass; today we saw how Whitney Bauman and Kevin O'Brien send readers of Grounding Religion: A Field Guide to the Study of Religion and Ecology on their way. "As authors and editors," they start, "we are worried, that this book might be a bit of a bummer."

As "Religion and Ecology" wends to a close - next week is for student presentations and the final class for closing syntheses - we experience the way two of our main texts wrap things up. Wednesday we'll reach the soaring conclusion of Braiding Sweetgrass; today we saw how Whitney Bauman and Kevin O'Brien send readers of Grounding Religion: A Field Guide to the Study of Religion and Ecology on their way. "As authors and editors," they start, "we are worried, that this book might be a bit of a bummer."

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.png)