"Religion and Ecology" had a field trip to the Met today, to see "Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature" and take a stroll through the Asian art wing looking for Buddhist works, but, as often happens, many students weren't able to come. The museum is too far from school for students with classes immediately before and after ours to be able get there and back. I'd asked those whose schedule didn't allow going today to go on their own time, and everyone to share a few pictures with some thoughts online, but many probably won't go. How to make them want to? Here are the pictures, with comments, which I posted...

I found myself going back and back to this early ink painting of Friedrich's - this is the lower right corner. I don't know how he manages to convey misty moonrise light so well...

Seeing this famous painting, familiar from many a book cover, in the context of Friedrich's other works, was quite revealing. In no other work is the human form so large or dominant. The human is lost or exalted or absorbed in nature in most of the others... making this a most unrepresentative work of his!

I think Friedrich's landscapes pulse with sentience, especially when uncluttered by explicitly Christian symbols! "Bushes in the snow (From the Dresden Heath II)" is one of a pair which flummoxed viewers when originally displayed for the depicted trees' unremarkableness, and one an otherwise enthusiastic reviewer of this exhibition found uncanny and threatening. Is nature so inhuman?

In Friedrich's painting of the Alpine peak "The Watzmann" (this is a detail), he's put the mountains he knows and loves in the foreground, with the mountain peak Friedrich never saw (but a friend had sketched for him) in the background. I'm charmed by his familiar trees, and intrigued by the intermediate mountain he conjures up...

The different meanings people projected onto this painting are fascinating. Is the forest friendly or, as some of the nationalistic interpretations after the defeat of Napoleon imagined, hostile, even murderous - at least toward invading Frenchmen?!

This is another wonder of atmosphere. It looks misty but if you get close, every detail of the tree's branches is there - as if you'd approached it through a fog.

This is also my favorite of his explicitly Christian works, perhaps because the crucifix is not facing us but looks away into the distance...

This 14th century painting of Kannon (Avalokitesvara) in the Japanese collections is one of the few Buddhist works with natural details beyond the figures of enlightened anthropomorphic beings...

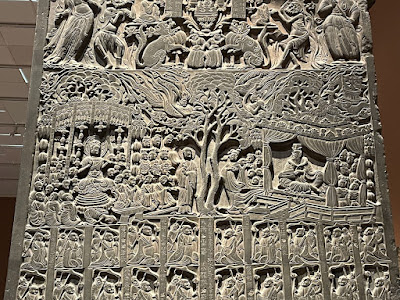

Closeup of the 6th century Chinese stele in that first hall of Chinese art, with glorious animated trees (which reminded me of Friedrich's "Bushes in the Snow" above). Or maybe it's a single double-stemmed tree, relating to the story of how the (male) disciple Sariputra took the form of a woman - that's them on both sides of the tree(s)!...

It's worth going to the Caspar David Friedrich exhibition just to see this amazing painting. This isn't all of it, but registers my surprised discovery that the human figure, perhaps a monk, is not alone before the sublimity of sea and storm and sky, but is kept company by birds.

Doesn't this make you want to go too, for a closer look of your own?

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)