The work of the prodigious and prolific Horace Kallen, his biographer confirms, is a rabbit hole. "Everything Kallen wrote and said over the course of over 70 years is interconnected," he tells me, "So once you get going, you can’t stop." Yet stop I must!

All

I have to do is write an introduction for a talk he gave. The pull of the rabbit hole is great, though, not least because the talk in question isn't very interesting on its own. It's being published because Kallen left few things unpublished, and he

was a central figure in the school, and had some interesting ideas. So I feel I have to go beyond the talk (without quite saying it was deservedly unpublished) to introduce Kallen and his work. You had to be there, I'll say: if Kallen's argument was unoriginal, the fact that he was the one making it and the

way he made it gave it significance beyond its words. Everyone there will already have known Kallen's distinctive commitments and supplied these as backdrop and horizon of his remarks. The setting was a symposium honoring New School's great director Alvin Johnson, so it's also about the distinctive commitments of the School, which Kallen helped define.

The talk was called "Are there limitations to toleration in a free society?" and Kallen's answer was basically: No. Those dedicated to intolerance are not philosophically inconsistent when they take advantage of the tolerance of the tolerant - even if it is to destroy the "Society of Toleration." (A favorite example from the 19th century Louis Veuillot:

Upon your principles you are bound to tolerate us; upon ours we are right to persecute you. [5]) Inconsistent, however, are those who claim that the Society of Toleration must defend itself by refusing to tolerate intolerance. It's a conundrum

constitutive of a free society [2]. Kallen calls it the "Predicament of Toleration," and offers no philosophical way out of it.

Delivered presciently a month before Joseph McCarthy claimed to have a list of communists in the State Department, Kallen's aim seems mainly to have been vindicating an American tradition of toleration of dissent threatened by political opportunists exaggerating the threat of communist infiltration. He quotes Jefferson's first Inaugural:

"If there be any among us who wish to dissolve this union, or change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed, as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it." [4]

Even if the threat were significant, however, it would be not only inconsistent but self-defeating to seek to protect tolerance through intolerance.

[I]f the tolerant tolerated the intolerant, the latter wold put an end to toleration; if the tolerant suppressed the intolerant, they would themselves put an end to toleration. In either case, toleration would be kaput. [5] Is the Society of Toleration doomed?

Kallen presents the long view. The predicament of toleration is nothing new. Indeed, for most of human history - and all of human history in most parts of the world - the idea of tolerance was an outlier, often persecuted. Kallen discusses Catholics medieval and antimodern, Hitler and Lenin, but reminds us that the idea that

error has not the same right as truth [6] has a venerable history. But America is safe,

the strongest, the best-informed, the richest, the freest and the most stable of the nations of the world [7], strengthened by the Supreme Court 8], innumerable

voluntary associations - and by university presidents rebuffing the intolerance of intemperate alumni.

Where an institution - be it a university, a corporation, a church, a state or a learned society - penalizes variance, it converts opinion into dogma, the search for truth into the iteration of creed, and honesty into hypocrisy [9]. The advocates of a Society of Toleration share Jefferson's conviction that

"It is error which needs the support of government; truth can stand by itself" [6] but know that the victory of truth is never assured.

That the law, so conceived and so administered, protects threats to the very existence of toleration, that it extends a suicidal invitation to its enemy to use it as the means of its extinction, those to whom freedom is the fighting faith well know. They accept the risk. [10]

Kallen winds up by saying he knows of no way to

save the Society of Toleration from its predicament and still keep it a society of toleration [11]. He hasn't presented any new ideas, nor does he claim to have. The phrase "predicament of toleration" may be new, but every advocate of free societies has known it. What makes this a specifically Kallenian presentation lies in the way he makes the argument.

Central to Kallen's argument is religious language. The phrase "fighting faith" is only one of many such uses, perhaps the most explicit of which came a few pages earlier:

it might be said that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

which the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted on December 10,

1948, offers us this faith in the equal liberty of the unlike to be the

common religion of mankind. [4-5]

And, indeed, his final words offer a religious proof-text:

In action, a free society always hazards its future on a faith which does not guarantee the outcome in advance. Faiths, William James tells us in the Varieties of Religious Experience, are hypotheses and may not make "rationalistic and authoritarian pretensions." There is "no scientific or other method by which men can steer safely between the opposite dangers of believing too little or too much." This is the predicament of belief. It is particularly the predicament of belief in toleration. [11]

The reference to James, seen to have anointed Kallen his successor, fundamentally reframes the "predicament." What might otherwise be a paralyzing paradox or an existentialist challenge is instead shown to be a puzzle that can (and can only) be gotten past through action. Every belief is a bet. Kallen could have referenced James'

Pragmatism at the end of this lecture, or even

The Will to Believe (from whose Preface the lines he quotes actually hail) but it's significant that he rather cites

Varieties of Religious Experience. Kallen taught and wrote about religion from his first year at the New School (his

Why Religion? purported to be an extension of

Varieties). While religious traditions are models of intolerant authoritarianism, religion properly understood offers hope to the society of freedom which was his true object. The struggle to keep on struggling requires experience and even institutions best characterized in religious terms. The work of a free society is not just political or philosophical but spiritual.

When Horace Kallen gave that speech exhorting people not to give up on what he sometimes called "the American idea," it thus differed in important ways from the sources he cites - Jefferson, Madison, John Stuart Mill, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. We sense that difference in the long view narrative, in which the forces of intolerance vastly preponderate. It takes something like religious faith for the Society of Toleration to continue to offer the "suicidal invitation" to the intolerant, even as the enemy circles around you.

What Kallen thinks makes it possible to resist the temptations of intolerance is the experience - of individuals and of society as a whole - of

a social atmosphere, a climate of opinion, a consensus, in which toleration has become dominant, which he somewhat confusingly describes as

creations of a firm belief, embodied in works, among people who are different from each other and have learned to live together with each other in equal liberty, also for the intolerant [11]. Kallen dedicated his life to understanding freedom (he was that very semester teaching "Problems in the Philosophy of Freedom"), but the

experience of it seems to arise especially in a society committed to what had by that time already become his greatest legacy, "cultural pluralism."

The safety of freedom, he said,

consists in the number and diversity of the free [2].

I'm not sure where to go from here....

1. The

"diversity of the free" could offer an in to Kallen's theory of "cultural pluralism," but I don't really want to wade into that - even though it's the only thing he's now remembered for. (It's in the talk in abbreviated form, where he says of the society of toleration

Its wholeness will be that of free inner orchestration [2].)

2. I'd rather segue from "social atmosphere" to the "atmosphere of freedom" which the New School claims for itself in its catalogs from that time. (This is from the 1950-51 one.) I don't think many of the other folks at that symposium used Kallen's religious

argot, but all were happy to inhabit the pluralist intellectual culture Alvin Johnson had just a few years before credited to Kallen: "With the development of the institution, Kallen's position, which had at first seemed far off center, came to express more nearly than any other the real meaning and objectives of the New School.” Johnson discussed Kallen’s now forgotten role in constituting the faculty of the University in Exile, which had offered refuge to all the other speakers at the 1950 symposium:

They were selected with a view to their development of creativeness, in the frame of the New School adult education organization. With their selection Kallen had much to do; but Kallenism had more to do with it. Kallenism is the principle that we live in a multiple world, multiple in national and racial characteristics, in art and letters, in religion and philosophy. It is the essential doctrine of Kallenism that out of multiplicity alone, multiplicity accepted with eager interest, can the creative process grow, in matters intellectual and in life itself.

Foreward to Freedom and Experience: Essays presented to Horace M. Kallen, ed. Sidney Hook & Milton R. Konvitz (Ithaca & NY: Cornell UP for The New School for Social Research, 1947), xii, xvi

"Kallenism" was connected to the now nearly unintelligible adult education mission of the New School, for which, too, Kallen was a major

advocate. (In the

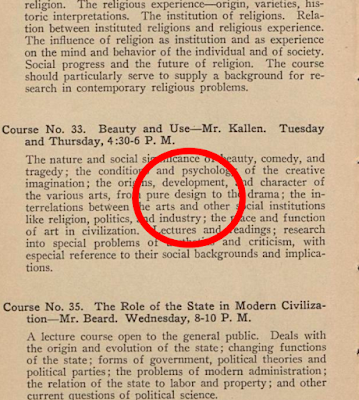

picture below, Kallen gives a prize in adult education, in 1951.) The professionalization of the universities was something Kallen's teacher James had already

railed against. Kallen and his school were part of a public education movement, significantly shaped by pragmatism, whose very self-understanding sounds in the today's academy like a put-down:

popularizers of philosophy. The New School's great contribution on the eve of the establishment of the University in Exile, the

Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, was a work of popularization. (Kallen wrote a fascinating series of articles for it, incidentally, bridging psychology, philosophy and religion:

Behaviorism; Blasphemy; Coercion; Conditioned Reflex; Conformity; Consensus; Cults; Functionalism; Innovation; Intransigence; James, William; Modernism; Morals; Persecution; Pragmatism; Psychoanalysis; Radicalism; Reformism; Self-Preservation.)

But the rabbit holes I'm really tempted go down have to do with religion. At least three are beckoning to me.

3. One looks to that

weird poem he published just at the moment, which imagines human history as a beach pounded by relentless waves of gods, conjured by human fear, with America a kind of respite. That could take one into the ideas of a kind of civil religion of religious pluralism or "religion of religions" (the biographer thinks Kallen scooped Robert Bellah's influential 1967 essay "

Civil Religion in America") which will appear in Kallen's quixotic

Secularism is the Will of God in 1955.

4. Another looks more at the Jamesian legacy Kallen claims, perhaps using this powerful early formulation:

The world is all conflict; it contains evil, it is full of menace and danger. But these are not eternal. Man is genuinely free, he can change his world and himself for the better. He can ameliorate by his very faith. In a universe rich with actual contingencies, faith and works even of so small an item as man, may be and often are, pregnant with tremendous human and even cosmic consequences. You are, therefore, entitled to believe at your own risk, and since the world is in flux, the mere existence of that belief may be just the one needed factor to make its object real. Nothing is eternally damned, nothing eternally saved; the contributing value to the validity of your beliefs, to the strength of your life, is as much yourself as the environment to which you must adapt yourself.

This is giddy-making but the really fun thing about using it would be that it appears in Kallen's early essay "Hebraism and Current Trends in Philosophy" (1909)

. For Kallen, Willam James, as an American and a Darwinian, helps restore an ancient way of thinking with roots in the biblical tradition - especially in Job, who, in fact, turns up in the next sentence:

But this is only the modern way of asserting in an unfortuitous environment "I know that He will slay me, nevertheless will I maintain my ways before Him."

Judaism at Bay: Essays toward the Adjustmnt of Judaism to Modernity (NY: Bloch, 1932), 12

That line of Job (13:15) is Kallen's most cherished mantra. It shows up everywhere - for instance in the conclusion of his thousand-page

Art and Freedom (1940), the expanded version of the "

Beauty and Use" essay we've often used in class. It's arguably the spirit behind the argument for tolerating the intolerant who are committed to slaying you. (In

The Liberal Spirit, published in 1948, Job 13:15 is presented as the "ultimate statement of... humanism," and rendered "Behold, he will slay me; I shall not survive; nevertheless will I maintain my ways before him" (187).) The ideal of the Society of Toleration is really "Hebraism."

5. A final rabbit hole has to do with the Hebraism of the New School itself. All of the speakers at the 1950 symposium - excepting the past and current Presidents Johnson and Simons - were Jewish, though this probably

wasn't something they would have drawn attention to. Kallen may have been the explicit link between the New School and Jewish experience, safe perhaps because he was an American (though also an immigrant) and the scion of James, Royce and Santayana. Kallenist pluralism, with its resolute refusal of convergence, its celebration of the "equal liberty of the unlike" and the "diversity of the free" constitutive of a society of freedom seems to me profoundly shaped by the struggle for Jewish identity in the face of Christian, Americanist and other supersessionisms.

One of the most interesting things I found in the Archives (they've since digitized it!) was a "

Memorandum on the New School" written by Kallen at about this time (early 1950s), which asserts that New School had for a long time been pioneering a way of integrating Jewish tradition into education. It's fascinating, and spells out in an uprecedented way things we have long surmised about the Jewish demography and ethos of the place. But it doesn't suggest there is something Hebraist about the very pluralism of the place. Kallen's preferred language, at this stage at least (though Hebraism continued to be a central motif of his course "Dominant Ideals in Western Civilization"), is the language of freedom - and of religion! In another contemporary archival find, a letter Kallen sent to president Simons in 1951 (not a Jew though married to one), we learn that Kallen regarded New School itself as a sort of religion!

Men and women who understand the meaning of freedom, and of its relation to truth, and whose belief in them has the quality of religious commitment, are necessarily in the minority. The [New] School’s successful functioning must needs depend therefore on the support of such a consecrated minority, whose relations to it must be like membership in a church. Indeed, in many ways, the New School does constitute a free religious society, whose faith is the freedom of the human spirit, and whose rites and works are the School’s characteristic study of freedom’s nature, forms, circumstance, growth, and configurations in free society.

Whew!

Too many rabbit holes, and each seeming to whisper "someone should write an essay about this!"

What to do?

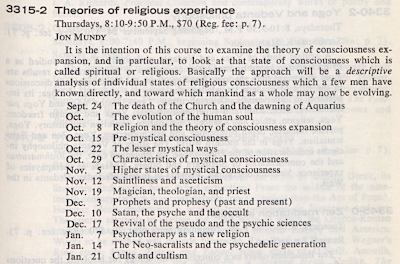

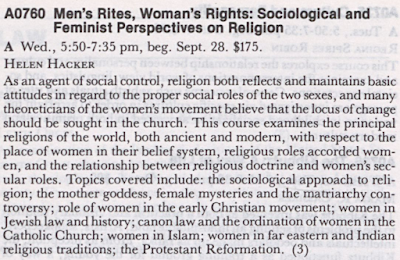

We opened "Theorizing Religion" to the public today as part of the Festival of New... four of the people who signed up even came! But it gave me an excuse to invite Matthew Kaufman to speak, and to put together a series of archival images chronicling religious studies at the New School - or perhaps New School history through religious studies.

We opened "Theorizing Religion" to the public today as part of the Festival of New... four of the people who signed up even came! But it gave me an excuse to invite Matthew Kaufman to speak, and to put together a series of archival images chronicling religious studies at the New School - or perhaps New School history through religious studies. 1995: Our tradition of interrogating secularism is alive and well

1995: Our tradition of interrogating secularism is alive and well