In the Guardian, so valuable a corrective for the narrowly US-aligned coverage in American news sources, an apocalyptic postcard scene of the record-breaking fires in Turkey - had you heard about them? A piece on heat records in Greenland spells out global consequences.

Friday, July 30, 2021

Thursday, July 29, 2021

Queer family

Hello, family! Today is the Feast Day of Mary, Martha and Lazarus of Bethany - special friends of Jesus. Maybe even more special than we're told. (This early 16th century Valencian family portrait is a rarity.) Kittredge Cherry, whose QSpirit updates I follow, directs us to a reflection from MCC Moderator Nancy Wilson.

Hello, family! Today is the Feast Day of Mary, Martha and Lazarus of Bethany - special friends of Jesus. Maybe even more special than we're told. (This early 16th century Valencian family portrait is a rarity.) Kittredge Cherry, whose QSpirit updates I follow, directs us to a reflection from MCC Moderator Nancy Wilson.

Jesus loved Lazarus, Mary and Martha. What drew Jesus to this very non-traditional family group of a bachelor brother living with two spinster sisters? Two barren women and a eunuch are Jesus’ adult family of choice. Are we to assume they were all celibate hetero-sexuals? What if Mary and Martha were not sisters but called each other ‘sister’ as did most lesbian couples throughout recorded history?

My friend M reminds me that sibling-language has been used in all sorts of ways (not least by Jesus), but this suggestion delights me. Whatever their relationships, the household of Lazarus, Martha and Mary is a unit, complete. Jesus felt at home there, and so can we.

Wednesday, July 28, 2021

Jitters

My first appointment back on campus is four weeks from tomorrow, the Thursday of Orientation Week. By that time I'll have officially confirmed my vaccination status (everyone on campus - students, faculty and staff - must be vaccinated unless eligible for an exemption), and will also somehow have tested myself for covid and, presumably, tested negative (required within 7 days of first arrival back on campus). The reality of what being back in person will

demand is just dawning on us. At present, all classes are to be held in person, even though a Faculty Senate survey conducted in early June - when the outlook was rather brighter than it is today - recorded considerable apprehensiveness. I was among 28% who would be happy with a 50/50 split of in-person and remote teaching, part of the majority resistant to the idea of going fully in person. I don't know how students feel but at least some surely share our caution.

Tuesday, July 27, 2021

PoGitA

Monday, July 26, 2021

Audible gasp

Sunday, July 25, 2021

Saturday, July 24, 2021

Belvedere

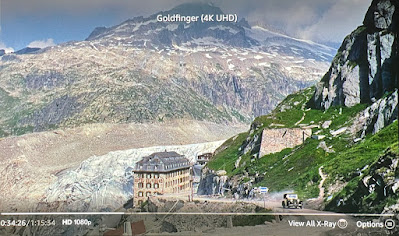

In search of late summer diversion, we watched the hightest ranked James Bond film, 1964's "Goldfinger." The story is appalling, but what caught me was this scene in Switzerland. That's the Hotel Belvedere at the Rhonegletscher (the glacier of the Rhône river) in Switzerland, a place connected to a branch of my family, and one we often visited while hiking in the Wallis valley. My sister had a summer job there and, if I'm not mistaken, it was the destination of my very first trip, shortly after being born. I might be bemused that I'm recognizing family history in a famed movie landscape when, in fact, millions of people - starting even before I was born - must have been recognizing the movie in the landscape! But this unexpected reencounter gave me occasion to confirm something I'd heard - that the glacier of the Rhone, caverns in which you could once enter right from the hotel, has melted so far back that it's not even visible from the hotel any more. A drone film shot a year ago confirms this. Vertigo!

Friday, July 23, 2021

Satori

I guess I never posted a picture of this sculpture, which was erected in Morningside Park in May. Called "Reclining Liberty," it light-heartedly combines a familiar New York character with an ancient Buddhist pose. Artist Zaq Landsberg lets viewers decide what it means. (Many younger ones also climb all over it.)

I guess I never posted a picture of this sculpture, which was erected in Morningside Park in May. Called "Reclining Liberty," it light-heartedly combines a familiar New York character with an ancient Buddhist pose. Artist Zaq Landsberg lets viewers decide what it means. (Many younger ones also climb all over it.)

I had the pleasure yesterday of showing it to a friend who happens to be a Buddhist, and has just been through a really rough year. I didn't tell him what we were going to see, and had us approach from the right. We saw Lady Liberty's feet before we knew whose they were, or what she was doing. "It's the Buddha!" he gasped, happily astonished.

Thursday, July 22, 2021

Land of big numbers

This graphic is from the South China Morning Post. As unthinkable amounts of water fell (the huge cube is just the city of Zhengzhou), 33 deaths have been announced. That's a number a Shanghai friend taught me appears often in official disaster reports and means: many, many more.

This graphic is from the South China Morning Post. As unthinkable amounts of water fell (the huge cube is just the city of Zhengzhou), 33 deaths have been announced. That's a number a Shanghai friend taught me appears often in official disaster reports and means: many, many more.

And more rain is in the forecast.

Wednesday, July 21, 2021

Diluvian

A student in the class just finished responded to my comments on her final paper and added: Recently, the extreme weather in Henan Province caused by climate warming has completely disturbed the original urban order, which has aroused my deep reflection. The Anthropocene is indeed a topic that should be paid attention to.

A student in the class just finished responded to my comments on her final paper and added: Recently, the extreme weather in Henan Province caused by climate warming has completely disturbed the original urban order, which has aroused my deep reflection. The Anthropocene is indeed a topic that should be paid attention to.

(Image)

Tuesday, July 20, 2021

Anthropocene stories

Storytime! Stories were a major theme in the "Anthropocene Humanities" course, building on Julia Adeney Thomas' typology of historical narratives for the Anthropocene and Amitav Ghosh's critique of realist novels for telling the wrong kinds of stories for the Anthropocene. The humanities contribute to Anthropocene reflection an appreciation for the indispensability of stories to human life and history - and a critical awareness of the possibilites opened, and closed, by stories of various kinds. The midterm paper (due in the fourth session, 9 days in!) was about what sorts of stories the Anthropocene demanded. And of course our final session, anchored in Donna Haraway's "Camille Stories," generated a half dozen remarkable "speculative fabulations" of our own. But a few students also availed themselves of the option of writing a story as their final paper.

These were each thoughtful and creative and - being stories - don't really lend themselves to being summarized! But let me try to describe them anyway, starting with the more conventional and moving toward the more complex. Individually and together they evoke worlds of gloom, concern and hope.A few of the briefer ones tell of post-apocalyptic worlds familiar from science fiction, in worlds ravaged by anthropogenic disasters and viruses. One tells of a farmer whose field hands fall ill; it turns out to be a new virus, borne by mutated wheat, which devastates the human population. Two others describe a world where only select few can be saved (under a "Dome" in Australia in one story, an "Ark of Doom" in the other) - but what one calls "the ugliness of human nature" is revealed as people fight to enter or, having made it in, turn on each other. As humanity approaches its inevitable death the only peace is found among Tibetan monks chanting sutras in the Himalayas. Another tells of a pair of siblings at a time when a lethal virus is killing people all around. The few uninfected people are called to shelter for the future of humanity, including A - but his sister B is ill. She tells him to leave her but he insists on taking her with him to the shelter where, although her condition has improved with their shared hope, she is turned away. This is the right thing to do, the student writes, but let's do what we can to ensuer we never find ourselves in that situation.

Abortive hope appears in a few others. One takes the form of a letter, written by the last surviving human on the planet: if you're reading it, perhaps you're a descendant of the people who left in 10 space ships in search of a new planet? The letter describes how humans destroyed the earth, and darky worries that, should any of the shape ships find another planet to inhabit, will probably take it to Anthropocene too. Another tells of a scientist whose years of efforts to develop a plastic-consuming plant have been fruitless, even as plastics, piling up everywhere and ruining the oceans, have started to mutate. Suddenly he notices a spot of green - a leaf from what turns out to be a fast-growing plastic-decomposing plant! It ends up preventing the plastic apocalypse but, the storyteller concludes, As people are buried in joy, a tremendous carcass of a dead whale is floating in the sea, whose body is occupied by new unknown organisms and materials.

Salvific green appears in another, more elaborate story. Two explorers - conveniently named Mark and Mary - are part of a series of teams called "Oasis," dispatched to the desertified world outside a domed human settlement for signs of surviving biological life. Their supplies are running out, and they seem likely to join the past teams who never returned.

“Mary, how much food do you have?” Mark asked.A little more complicated, even conflicted, is the story about a self-doubting young Siren named Argel. He (Greek sirens are half bird half woman but these sirens have fish tails and at least this one is male) wonders why sirens are thought to be ugly, and why they have to tempt sailors to their doom. Did god create them to kill? He's drawn to human beings, though only one boy smiles at him. But at the same time the boy smiles, other humans are dumping colorful plastics in the ocean. Argel notices that sirens cause more shipwrecks when humans dump more plastics, but doesn't want to be evil. He dives deep into the sea, passing shoals of colorful fish and even more colorful plastics, until his last breath is spent. There was a little turtle lying on the reef where Argel left, the story ends. It turned over on the reef, and its four feet were wrapped with fishing nets which were as green as its shell. The student explained that she left Argel's questions unanswered for the reader to ponder.

The last story, finally, is about a mermaid - yes, the narrator says, a mermaid: they really exist! This one never knew her parents but was raised in the middle of the Pacific by her grandfather - also a mermaid! He taught her to swim, but also about human language and civilization; he said a stranded sailor had taught him. One day a tanker crashes on a shoal. Her grandfather tries to help the fish and birds dying in the spilled oil, and the mermaid helps him; when the ship collapses on them, he shields her with his body. She wakes up on a beach where someone is talking to her - a human! "I know you talk," he says, and asks if she wants to know how her grandfather is doing. She learns that he's died - but the man says he can be revived - by science! They'll be able to make her human, too - won't she come along? She agrees but asks to have a final look at the ocean, and escapes into the waves. Why did she run away? asks the narrator rhetorically, Because the sea was too beautiful.

And why do I know this mermaid? Because I am her. My grandfather is a knowledgeable scientist, and my parents used to be researchers in the "Human-fish gene exchange" laboratory in the human world. Grandfather discovered that the purpose of my parents' research was to create the so-called "Mermaid", so that human beings could plunder the ocean more wantonly. My parents' research had been successful but my grandfather thought that a great disaster was coming, and finally they had a conflict. The accident led to the death of my parents. In order to stop the plan, my grandfather absconded with me and the core achievements in the laboratory. In order to avoid capture, he turned me and himself into mermaids, managed to erase all my memories, fled to the sea, and destroyed all the research findings. The people who found us have been searching for us for a long time. The arrogant guy who talked to me wanted to persuade me to go back to the human world in order to continue the research of "Human-fish gene exchange" on me. He was so smug that he let me escape easily, probably because in his mind, human life has infinite charm. After that, I continue to travel through the ocean, always doing the last thing my grandfather and I did together - saving the endangered lives in the ocean with my own tiny power. I am a mermaid, although without much power, but still adhere to protect my home.

I think Scheherezade would be impressed by all these stories, and cyborg prophetess Haraway too; I know that I am. I want to find a way to use some of them in my fall course - optimally not only with the writers' permission but with their participation too! Stories are able to capture complicated emotions, to explore the ways in which humans (and others) might respond to calamitous and dehumanizing times, in solidarity with the whole fragile world.

Bootleg AQI

We had weird weather here today, the sky a dirty yellowish white, the buildings on the horizon a soupy grey and and the sun a fuzzy orange. The light reminded me of Shanghai so I checked the AQI index and saw we were in unhealthy territory. By evening it reached 167.

But where could all that fine particulate matter be coming from? Eventually we learned the reason. We'd read that the Oregon Bootleg fire was generating its own weather, smoke in a satellite view streaming eastward... should have remembered it could reach us!

But where could all that fine particulate matter be coming from? Eventually we learned the reason. We'd read that the Oregon Bootleg fire was generating its own weather, smoke in a satellite view streaming eastward... should have remembered it could reach us!

Monday, July 19, 2021

Finale

I've made my way through all the final papers for the Renmin summer school. Most are impressive, considering they're written in a second language, in a field far from the student's major - and, of course, a field full of polysyllabic neologisms like "Anthropocene"! The consensus of most of the essay writers seems to be that Chinese tradition has the resources to offer a way out of the Anthropocene. This wisdom was frequently presented in terms of a seamless tradition asserting the unity of humanity and nature (天人合一) stretching from ancient Taoism (not the Daoism I gave them some materials about) and Confucianism to contemporary ideas of "ecological civilization" - so frequently and so seamlessly that I sense the presence of a shared source. Occasionally the Chairman of Everything is even named, though not as often as his wooden slogans about the "community of life" and the "green waters and green mountains [which] are also gold mountains and silver mountains."

The more interesting papers made more complex arguments. One each discussed "ecological socialism" and "historical materialism" by name (who knew the young Karl Marx had anticipated the Anthropocene in distinguishing "free nature" from "humanized nature"!) One suggested that what united the apparent differences between Daoists, Confucians and Legalists (only mention of this important school!) is a civilization-defining "pragmatism" on display also in recent appropriations of socialism and capitalism. One responded to Roy Scranton's argument that the Anthropocene demands we learn to die as a civilization (based on the old saw that to philosophize is to learn to die) with a knowing deployment of Confucius' agnosticism about the afterlife: "how can we know death if we don't know life?" And one exquisitely compared Chinese landscape paintings with western Renaissance perspective to demonstrate the "liquid ecology" James Miller had shown us at work in Daoism, one which dissolves not only the boundary between the human and natural worlds, but between both of these and the supernatural.

One brilliant essay traced a famous ancient folk tale (愚公移山) about a man who thought he could move a mountain with the help of his future descendants, his naive faith rewarded by the gods who granted his wish, from ancient times through a famous discussion of Mao's (the people take the place of the gods) and into the present (where technology lets us do the work of the gods ourselves) through discussion of two recent Chinese sci-fi movies! At the end of the story of "Yugong Moves the Mountain", the Emperor of Heaven was moved by Yugong's sincerity and ordered the two sons of Kua'e to carry on the two mountains. But what the story does not tell us is what is left after the mountain was removed. Is it magnanimous? Is it a gravel wilderness? Or a bottomless abyss?

Another suite of essays introduced me to contemporary Chinese art works, novels and even a fashion collection engaged implicitly or explicitly with the Anthropocene. These works were anguished about the extent of ecological devastation, and less sanguine about the possibility of restoring harmony" Song Chen's "Healing Land," an installation assembling polluted soil samples from around the world in giant "soil babies" on "soil placentas"; the "Story Behind" series of Xu Bing, which recreated traditional landscape scenes out of garbage (I saw two of them in Beijing); Chen Qiufan's astonishing "near Anthropocene" novel Waste Tide (the English translation of which I've started reading); another novel actually called Anthropocene (人类世) by one Zhao Defa (not available in translation but it sounds fascinating); and the Spring Summer 2021 collection of Chinese designer Mithridate, also called "Anthropocene," and presented with great drama at the Serpentine Gallery in London. Students also commended western works, from Ian Angus to Peter Berger's Introduction to Sociology to a BBC series called "Human Planet."

But perhaps the most interesting were the stories which not quite a fourth of the students chose to write - which I'll tell you about tomorrow.

Sunday, July 18, 2021

With relish

Saturday, July 17, 2021

Mosquito-cene

Taking my time, I've made it through two-thirds of the final papers for my Renmin summer school course on "Anthropocene Humanities." Filtering out the platitudes about "ecological civilization" which many students felt obliged to include, there's lots of interesting stuff and some really insightful arguments. Several students opted to write stories, and they are all wonderfully creative and revealing - I'll share some of them when I've finished all the papers.

But for now, here's something on a lighter note, a second-hand story:

When I mentioned the concept of the Anthropocene to my friend, she summed her opinion up with a short story. She said that summer had arrived and mosquitoes were popping up in her dorm room. She was bitten all over, and once, woken up at night because of the buzzing noise, she accidentally heard a mosquito say to its fellows: “We have sucked the life out of that large mammal and she can not defend herself. I declare this dormitory to have entered The Times of Mosquitoes!” The rest agreed, and began to recount the feats of their people since the days of warmer weather... My friend went back to sleep. She knew that mosquitoes would disappear with just a spray of insecticide, or at latest, come winter, would no longer exist, so she thought these were no different from the now-dead mosquitoes she had seen before, except that they had named the age of mosquitoes before dying.

Before returning to her own argument, the student wryly concludes:

Clearly she is one of the people who agree with the claim that man is nothing compared to nature.For my part, I'm thrilled that she's telling her friends about the class!

Friday, July 16, 2021

Apocalyptic

Thursday, July 15, 2021

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

More speculative fabulation

Here are three more stories, starting 75 years from now, by students in my Chinese summer school class.

By 2096, I am living on a very different planet -- a planet that is much harder to live on. I have seen the process of rising sea levels, higher temperatures, and more extreme weather events. The areas suitable for human survival have further shrunk, and many island countries have been lost or disappeared altogether. Tropical rain forests were further reduced, glaciers shrank, and as mining and arable land were developed, there was less fertile land, and it became more difficult to extract food/wealth from the soil. Many species that had existed for thousands of years became extinct in the last 75 years. Continued global warming is making catastrophic weather more frequent, sea levels are rising to varying degrees around the world, and New York has built levees to keep out the water. Some coastal cities, such as Houston or Shanghai, have been abandoned due to hazardous weather.Tuesday, July 13, 2021

Speculative fabulation

Monday, July 12, 2021

Sunday, July 11, 2021

Frying pan

Wish I could superimpose a temperature map on the itinerary of our trip, so you could see how we went from 77˚ on the coast to 116˚ in a few hours on Friday (with a stop in 99˚ Temecula), then back, from 112˚ to 79˚ today (with stop in 100˚ Hemet). This scary map (from WaPo), with counterintuitive colors (the flame colors are 60s to 80s, 100 is ashen but the treacherous 120s are green!), gives an idea...

Saturday, July 10, 2021

Desert heat

Friday, July 09, 2021

Marooned hammocks

The topic of the latest session of "Anthropocene Humanities" was "Descularizing the Anthropocene," a subject not only dreadfully polysyllabic but, for China, a little delicate. I didn't say "religion" - but then I didn't talk about religion or the religions. I talked about those experiences of surplus feeling, especially in places of complicated interaction with other-than-human forces, which across history have taken the form of spirits. We ended with Bronislaw Szerszynski's brilliant typology of "gods of the Anthropocene" - superhuman agencies arising in ostensibly secular theories of the Anthropocene - but the way in was more subtle.

The topic of the latest session of "Anthropocene Humanities" was "Descularizing the Anthropocene," a subject not only dreadfully polysyllabic but, for China, a little delicate. I didn't say "religion" - but then I didn't talk about religion or the religions. I talked about those experiences of surplus feeling, especially in places of complicated interaction with other-than-human forces, which across history have taken the form of spirits. We ended with Bronislaw Szerszynski's brilliant typology of "gods of the Anthropocene" - superhuman agencies arising in ostensibly secular theories of the Anthropocene - but the way in was more subtle.

I started with a brief review of some of the last session's material on apocalypse - which can mean the end of the world but also the uncovering of great knowledge, something new and more true than the "world" which is ending. Apocalyptic times might be the dawning of something radically different, but the main experience is vertiginous, of the collapse of all we've come to think we know. Roy Scranton was our representative Cassandra: our civilization is dead! We're doomed, now what? This is terrifying, a presentiment of the loss of worlds of so many indigenous peoples across the planet, and many more are experiencing it every year - like those discovering that along with hundreds of humans, a billion marine animals were "cooked to death" in the recent heat dome over western Canada.

For others, including presumably most of us in my class, though, it's still just over the horizon, like the steady drumbeat of unassimiliably awful news like that of the Canadian crustacean Apocalype. (A good account of that diffuse unease is Jenny Offill's Weather, an excerpt of which I gave the class to read last week.) To engage these gentler, if also unsettling, experiences I introduced the concept of "solastalgia."

This term, coined by Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, characterizes the psychic distress attending the experience of environmental change, especially in the place you live. It's the paradoxical "homesickness you have when you are still at home." This includes the mourning attending the awareness of things that are no longer present - you used to be able to see X here, there used to be a Y here but it died - but shades into a foreboding about the future, the sense that more loss is certain.

This term, coined by Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, characterizes the psychic distress attending the experience of environmental change, especially in the place you live. It's the paradoxical "homesickness you have when you are still at home." This includes the mourning attending the awareness of things that are no longer present - you used to be able to see X here, there used to be a Y here but it died - but shades into a foreboding about the future, the sense that more loss is certain.

I shared a short video some students at Oxford produced a few years ago, where students used their immobilized faces as canvases for images of widening environmental destruction in the environs where they grew up. (At top, a man from North Dakota depicts nitrification of rivers from industrial agriculture; the woman above is hearing reports on how the air in Seoul will in coming years become harder and harder to breathe. At the end, they reveal their faces, quickly wiping off most, but not all of the paint.) Their mute witness is very powerful, and in many senses brings the Anthropocene home. I asked students in their groups to reflect on why and how this little film was made, and if they had any similar memories. One reported:

The trees near my house were gradually cut down. The buildings replaced the previously heavily wooded area. When I was a kid, I loved tying the hammock to trees and sleeping in them, but now it is hard to find two adjacent trees to tie the hammock. When summer arrived, the whole area was very hot and dry, and everyone was reluctant to go out.

I suppose something like solastalgia is common for most people in China, whose landscape has been transformed beyond recognition with wave upon wave of urbanization. It's not quite the shock at environmental change Albrecht had in mind, but I'll take the image of the child without a second tree to tie his hammock to.

Our discussion proceeded from these disturbed human faces to the "Prophecy" photos of Fabrice Monteiro, where materials found in various pollution and climate-impacted areas in Senegal are brought together (with the help of fashion designer Doulcy) in the form of jinns - spirits defined as much by pain as by power. It's an interesting way into religious imagination, the human form stretched painfully beyond itself. We'll talk next class about some Daoist ideas: more religions. In the meantime, a student shared some images by contemporary Chinese photographer Wan Yunfeng, which employ similar means - that's him, below - to make environmental devastation real to us.

Thursday, July 08, 2021

Tuesday, July 06, 2021

Post-apocalyptic

Monday, July 05, 2021

Swell loom

Happened on this gorgeous picture today in the gallery of locally based celebrity photographer Aaron Chang, "Wild Coast," shot recently at Point Reyes, a little north of San Francisco. Mesmerizing! It may be because it shares a color palate with a hand-woven rug a friend brought me years ago from El Salvador, but it looks to me like a

tapestry. Indeed it also evokes the movement of weaving on a loom, a living rug woven and unwoven like Penelope's shroud, the pattern endlessly changing but always beautiful. That's how the surf feels, of course. Chang, building on a long career as a surfing photographer, knows how the waves feel when you're in them, moving with them.

And then of course there's that insouciant seagull...

Sunday, July 04, 2021

Saturday, July 03, 2021

Friday, July 02, 2021

Dreaming of electric sheep

Thursday, July 01, 2021

头破血流

Well, my Renmin summer school course made it through the big centennial hoopla without incident. It certainly was a little strange meeting students the mornings of the days immediately before and after the grand celebration, but I decided it best not to mention it... and none of the students did either. (They had returned to their hometowns from Beijing just as commemorations climaxed.) Instead, they worked in groups to compile a list of works one might consult to make sense of the Anthropocene, which ranged from Rachel Carson's Silent Spring to Michael Jackson's "Earth Song" to Werner Herzog's "Grizzly Man" by way of western and Chinese science fiction (on which more anon). Of recent Chinese history or thinking nothing.

Well, my Renmin summer school course made it through the big centennial hoopla without incident. It certainly was a little strange meeting students the mornings of the days immediately before and after the grand celebration, but I decided it best not to mention it... and none of the students did either. (They had returned to their hometowns from Beijing just as commemorations climaxed.) Instead, they worked in groups to compile a list of works one might consult to make sense of the Anthropocene, which ranged from Rachel Carson's Silent Spring to Michael Jackson's "Earth Song" to Werner Herzog's "Grizzly Man" by way of western and Chinese science fiction (on which more anon). Of recent Chinese history or thinking nothing.

These sites lie deep within the Qilian Mountains, thus rendering the QR codes mysterious cultural “relics” for anyone who stumbles upon them, now or in the future, much like the large installation works created earlier by Zhuang Hui and which he chose to abandon in the Gobi Desert in 2014. The QR codes are functioning, not merely decorative, both in situ and in the gallery ...