Wednesday, March 30, 2022

Full

Tuesday, March 29, 2022

Monday, March 28, 2022

Requited

This being week 9 I had the class divide up in groups to discuss each of the "Picking Sweetgrass" section's first five chapters, and then form groups with someone in charge of each chapter, to think about how the argument flows. The chapters - each of which could be a free-standing essay - take the reader from experiencing the love of a garden as it feeds us to an appreciation of the synergy of the "Three Sisters" (corn, beans and squash - and a fourth, the gardener), to the work of the Pigeon family weavers of black ash baskets to a study finding that sweetgrass is healthiest near human communities who use it and eventually to to a chapter on living as a human citizen of the "Maple Nation."

This being week 9 I had the class divide up in groups to discuss each of the "Picking Sweetgrass" section's first five chapters, and then form groups with someone in charge of each chapter, to think about how the argument flows. The chapters - each of which could be a free-standing essay - take the reader from experiencing the love of a garden as it feeds us to an appreciation of the synergy of the "Three Sisters" (corn, beans and squash - and a fourth, the gardener), to the work of the Pigeon family weavers of black ash baskets to a study finding that sweetgrass is healthiest near human communities who use it and eventually to to a chapter on living as a human citizen of the "Maple Nation." What I hoped students would see is the way Kimmerer moves outward from thinking about gardens as the exception in human relationships with other species to something more like the norm - though embattled. In gardening human beings can feel a reciprocity of care with the plants they tend. In planting and caring for the Three Sisters, all species are nourished - and all are needed, as, without human beings, these domesticated species would perish. In members of a Potawatomi family of basket weavers finding black ash trees willing to become baskets, asking their permission to fell and then laboring to make them into a thing of beauty (all these images are from their FaceBook page), we learn of the responsibility one should feel toward the materials we use. In that and the sweetgrass chapter we learn of plant populations which thrive over generations because

What I hoped students would see is the way Kimmerer moves outward from thinking about gardens as the exception in human relationships with other species to something more like the norm - though embattled. In gardening human beings can feel a reciprocity of care with the plants they tend. In planting and caring for the Three Sisters, all species are nourished - and all are needed, as, without human beings, these domesticated species would perish. In members of a Potawatomi family of basket weavers finding black ash trees willing to become baskets, asking their permission to fell and then laboring to make them into a thing of beauty (all these images are from their FaceBook page), we learn of the responsibility one should feel toward the materials we use. In that and the sweetgrass chapter we learn of plant populations which thrive over generations because of wise human use - and how the loss of those human partners devastates their plant partners too. And learning that maples populations are being driven northward out of their traditional regions by climate change we are called to recognize our responsibility for them, who give us so much, and to use our gifts to protect them.

of wise human use - and how the loss of those human partners devastates their plant partners too. And learning that maples populations are being driven northward out of their traditional regions by climate change we are called to recognize our responsibility for them, who give us so much, and to use our gifts to protect them.

It is - or should be - gardens everywhere, humans sharing our gifts in reciprocal relations with other peoples, from the apparently local and private sphere of a vegetable garden to the planet threatened by climate calamity.

What did surprise me - though it probably shouldn't have - was that student accounts of their discussions and analyses were still caught in the language of the earlier sections of the book. Human people, they expounded, are able to learn from and even communicate with other species (plants as teachers!), to observe and respect them in a spirit of gratitude and reciprocity. Yes, yes and yes. But this section of the book is about picking sweetgrass. The basket chapter starts with the chopping down of a tree! As students read, this section of the book culminates in a discussion of the "Honorable Harvest."

What did surprise me - though it probably shouldn't have - was that student accounts of their discussions and analyses were still caught in the language of the earlier sections of the book. Human people, they expounded, are able to learn from and even communicate with other species (plants as teachers!), to observe and respect them in a spirit of gratitude and reciprocity. Yes, yes and yes. But this section of the book is about picking sweetgrass. The basket chapter starts with the chopping down of a tree! As students read, this section of the book culminates in a discussion of the "Honorable Harvest." Our appreciations were still from the stance of a species separate from the rest of nature: we observe, we thank, we even care for. But the basic fact that we use, that we take life to further our own, remains too difficult a thought. Committed to reducing, reusing and recycling we wish we could find a way to have no ecological footprint at all. The burden of "Picking Sweetgrass" is that wise use is not only possible but necessary. The community which Kimmerer calls the "democracy of species" (173) demands that we give but also desires that we take. It wants and needs us to be part of it.

Our appreciations were still from the stance of a species separate from the rest of nature: we observe, we thank, we even care for. But the basic fact that we use, that we take life to further our own, remains too difficult a thought. Committed to reducing, reusing and recycling we wish we could find a way to have no ecological footprint at all. The burden of "Picking Sweetgrass" is that wise use is not only possible but necessary. The community which Kimmerer calls the "democracy of species" (173) demands that we give but also desires that we take. It wants and needs us to be part of it. Kimmerer wouldn't be surprised at our inability to imagine use as anything but parasitic. Early in Braiding Sweetgrass she mentions a class for environmental protection majors where students were flummoxed when asked to describe "positive interactions between people and land" (6). In this section, she has something more like our class in view, telling of a similarly stymied "graduate writing workshop on relationships to the land."

Kimmerer wouldn't be surprised at our inability to imagine use as anything but parasitic. Early in Braiding Sweetgrass she mentions a class for environmental protection majors where students were flummoxed when asked to describe "positive interactions between people and land" (6). In this section, she has something more like our class in view, telling of a similarly stymied "graduate writing workshop on relationships to the land."  The students all demonstrated a deep respect and affection for nature. They said that nature was the place where they experienced the greatest sense of belonging and well-being. They professed without reservation that they loved the earth. And then I asked them, "Do you think the earth loves you back?" No one was willing to answer that. ... Here was a room full of writers, passionately wallowing in unrequited love of nature. (124)

The students all demonstrated a deep respect and affection for nature. They said that nature was the place where they experienced the greatest sense of belonging and well-being. They professed without reservation that they loved the earth. And then I asked them, "Do you think the earth loves you back?" No one was willing to answer that. ... Here was a room full of writers, passionately wallowing in unrequited love of nature. (124)Thursday, March 24, 2022

Sixteenth century, hello!

Wednesday, March 23, 2022

Budding confusion

Tuesday, March 22, 2022

Monday, March 21, 2022

Saturday, March 19, 2022

Friday, March 18, 2022

Skewed perceptions

This is fascinating and disturbing: "Americans overestimate the size of minority groups and underestimate the size of most majority groups." Not that I would have done that much better. (Red is the actual proportion.) Happy to learn that actual gun ownership is 32%; I would have guessed closer to the average 54% (though I also remember it being about only 25% not too long ago). But how could people (even in aggregate) think the US population 27% Native American, 27% Muslim, 29% Asian, 30% Jewish, 39% Hispanic, 41% Black, 64% White? Also 70% Christian, 30% gay or lesbian, 21% transgender, 30% New Yorkers and 32% Californians, 36% union members and 40% military veterans?

This is fascinating and disturbing: "Americans overestimate the size of minority groups and underestimate the size of most majority groups." Not that I would have done that much better. (Red is the actual proportion.) Happy to learn that actual gun ownership is 32%; I would have guessed closer to the average 54% (though I also remember it being about only 25% not too long ago). But how could people (even in aggregate) think the US population 27% Native American, 27% Muslim, 29% Asian, 30% Jewish, 39% Hispanic, 41% Black, 64% White? Also 70% Christian, 30% gay or lesbian, 21% transgender, 30% New Yorkers and 32% Californians, 36% union members and 40% military veterans?

Thursday, March 17, 2022

Provenance

Cleveland is one of the great cultural centers of the United States - its orchestra has for a long time been known as the best in the country, and its art museum is world class - but I've never had occasion to go there, or, really, to form any sort of idea of the place. Casting about for somewhere we might combine with our spring break trip to Columbus, I finally had the chance. We stayed within walking distance of the Cleveland Art Museum, and having arrived last night, easily spent most of today there. Our journey began with a CMA icon, the over 4000-year old Anatolian statuette, "The Stargazer." There were few other patrons, so we mostly had the galleries to

Cleveland is one of the great cultural centers of the United States - its orchestra has for a long time been known as the best in the country, and its art museum is world class - but I've never had occasion to go there, or, really, to form any sort of idea of the place. Casting about for somewhere we might combine with our spring break trip to Columbus, I finally had the chance. We stayed within walking distance of the Cleveland Art Museum, and having arrived last night, easily spent most of today there. Our journey began with a CMA icon, the over 4000-year old Anatolian statuette, "The Stargazer." There were few other patrons, so we mostly had the galleries to  ourselves, but as I was marveling at a 3rd c. CE statue of Jonah spit out by a not-quite-whale, part of the collection known as the Jonah Marbles, a museum guard with a French accent came over. These are among the most famous objects in the museum, he told me, but nobody really knows how or even whether all the objects in the collection belong together. Part of what is great about this museum, he added, was that it doesn't pretend to know more about the provenance of its works than it does. This proved true, and added to the pleasure of encountering works none of which I had seen before. My usual museum misgivings - how did this wind up

ourselves, but as I was marveling at a 3rd c. CE statue of Jonah spit out by a not-quite-whale, part of the collection known as the Jonah Marbles, a museum guard with a French accent came over. These are among the most famous objects in the museum, he told me, but nobody really knows how or even whether all the objects in the collection belong together. Part of what is great about this museum, he added, was that it doesn't pretend to know more about the provenance of its works than it does. This proved true, and added to the pleasure of encountering works none of which I had seen before. My usual museum misgivings - how did this wind up  here? - were somewhat muted by their honesty about the vagaries of the movements of objects across time and space. This stunning and rare Byzantine Egyptian tapestry icon was acquired from a Mrs. Paul Mallon in 1967, the online collection explains, but how she got it is unknown. Mrs. Mallon was the source also of a pair of 13th c. angels,

here? - were somewhat muted by their honesty about the vagaries of the movements of objects across time and space. This stunning and rare Byzantine Egyptian tapestry icon was acquired from a Mrs. Paul Mallon in 1967, the online collection explains, but how she got it is unknown. Mrs. Mallon was the source also of a pair of 13th c. angels,  whose caption was wonderfully tentative: Surviving in fragmentary condition, this pair of angels lacks lower arms, hands, wings, and attributes. Their original paint and gilding, now almost entirely lost, once rendered their garments a rich brocade and their hair a luxuriant gold. Nonetheless, in their graceful poses and sublime

whose caption was wonderfully tentative: Surviving in fragmentary condition, this pair of angels lacks lower arms, hands, wings, and attributes. Their original paint and gilding, now almost entirely lost, once rendered their garments a rich brocade and their hair a luxuriant gold. Nonetheless, in their graceful poses and sublime  faces - which may portray tragic interest, anguish, or deep concern - thei original delicacy and power are still evident.... Sublime in another way was this large early 14th century German carving of Christ and his beloved disciple, which put me in mid of the queer mystical idea I encountered a decade ago that they may have been betrothed at Cana. The caption here somewhat disappointingly mentions only John's resting his head on Jesus' "shoulder" (usually it's the "breast"), with no reference to the incredibly tenderness of the hands, but no matter. The work, like everything in this museum, was displayed in such a way as to allow

faces - which may portray tragic interest, anguish, or deep concern - thei original delicacy and power are still evident.... Sublime in another way was this large early 14th century German carving of Christ and his beloved disciple, which put me in mid of the queer mystical idea I encountered a decade ago that they may have been betrothed at Cana. The caption here somewhat disappointingly mentions only John's resting his head on Jesus' "shoulder" (usually it's the "breast"), with no reference to the incredibly tenderness of the hands, but no matter. The work, like everything in this museum, was displayed in such a way as to allow  "Christ and the Virgin in the House at Nazareth," c. 1640. I encountered this haunting work in a book in Paris twenty years ago and was devastated by it. If you look closely at this imagined scene of Jesus' childhood, you'll notice a pinprick of blood on his fingertip and, just as small but just as cosmic in power, tears on Mary's cheeks.

"Christ and the Virgin in the House at Nazareth," c. 1640. I encountered this haunting work in a book in Paris twenty years ago and was devastated by it. If you look closely at this imagined scene of Jesus' childhood, you'll notice a pinprick of blood on his fingertip and, just as small but just as cosmic in power, tears on Mary's cheeks.Cultural Garden

Wednesday, March 16, 2022

Shche ne vmerla Ukrainas

Tuesday, March 15, 2022

Ohio nature

Sunday, March 13, 2022

Friday, March 11, 2022

Spring breaks through

Spinoza?

Thursday, March 10, 2022

Not for show

Accidents of scheduling took me to two exhibitions today which seek to challenge the ethos of exhibition. "What is the use of Buddhist art?" at the Wallach Art Gallery tries valiantly to let its magnificent works from Columbia's collection of Buddhist art be encountered not as aesthetic or historic objects but as figures of devotion. The other, "Lenapoehoking" at the Brooklyn Public Library's Greenpoint branch, tries to conjure the genocide of our region's indigenous population and seed a kind of return.

For all its meritorious efforts, the former wasn't really successful. Captions explained why objects were made but the exhibit still isolated them from the rhythms of Buddhist practice, which we'd learned just enough about to know was incredibly specific, local to a particular time, donor and setting. (The Wallach Gallery, which had two other shows on in the same large space, has a unifying aesthetic so the curators' hands were tied.) The displays invited a kind of intimate looking but this will have been fundamentally different from the stance of those "using" these figures and texts. I didn't feel any of them as objects of salvific power except in the (perhaps intentional) reflections of two cases containing medieval Japanese figures above. Not that I can imagine a non-cheesy way of letting exhibition guests get a taste of the prostration, chanting, incensing, gifting with fruit and flowers or other interactions through which practitioners will have engaged these works (the Rubin Museum has thought all this through more comprehensively) but the airy silence, white walls and glass cases of the gallery encouraged only the usual quasi-religious devotion which art museums encourage.

Quite different was "Lenapehoking," which quite deliberately chose a library rather than a museum or gallery setting for the first Lenape-curated experience in the city. Above a bustling local library full of children and people using the free wi-fi, a darkened room presented five glass-beaded bandoliers, a turkey feather gown, and, against the darkened windows, three "tapestries" of dried vines of three native bean species recently "rematriated" to the area. Some local fruit trees will be planted in the roof garden of the library starting next week, too. Two of the bandoliers, including the one at left in the photo (from here), are from the early 19th century, after the Lenape had already been driven from their homeland, but pose in a suspended dance with new ones commissioned for this show. And yet the mannequins make clear that bandoliers are for wearing, and as one circles around them one starts to feel the absence/presence of the shoulders and hips they embraced, and is increasingly astonished at their durability and survival. The bean tapestries, meanwhile, full of pods full of seeds, conjure the upward and downward motion of vines and beans, death and future life. After a while what had seemed a small and straightforward exhibition proves instead to be a space of looping time of absence and promise, the scene of a crime and an opening to hope.

Both exhibitions were good to think with.

Wednesday, March 09, 2022

Come labor on

Surprise: the students in this year's "Religion and Ecology" class are charmed by Pope Francis' Laudato Si - though they're even more surprised than I am by this. One thing that especially caught their interest was the critique of capitalism, notably the section entitled "The need to protext employment" (§§124-29). Most welcome and unexpected!

If we reflect on the proper relationship between human beings and the world around us, we see the need for a correct understanding of work; if we talk about the relationship between human beings and things, the question arises as to the meaning and purpose of all human activity. This has to do not only with manual or agricultural labour but with any activity involving a modification of existing reality, from producing a social report to the design of a technological development. Underlying every form of work is a concept of the relationship which we can and must have with what is other than ourselves. Together with the awe-filled contemplation of creation which we find in Saint Francis of Assisi, the Christian spiritual tradition has also developed a rich and balanced understanding of the meaning of work, as, for example, in the life of Blessed Charles de Foucauld and his followers. (§125)

Teasing out what is going on here we realized that Francis' "integral ecology" knows that human beings need to mix our labor with the world to lead a full life. Labor is the way we maintain the relationships with "what is other than ourselves" without which we are incomplete. Neither contemplation nor - God forbid - consumption can achieve this. Like the ideas we've otherwise mainly found in indigenous thinkers like Robin Wall Kimmerer, Laudato Si´ sees us as inescapably part of the world, if only we can discern the right ways to do it. A revelation in a Christian text: you can get there from here?!

Monday, March 07, 2022

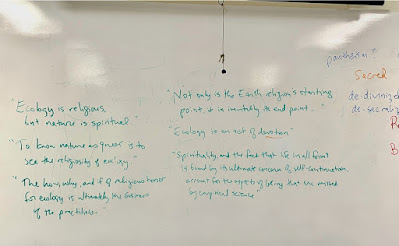

Ecology is an act of devotion

Saturday, March 05, 2022

Speechless horror

Wednesday, March 02, 2022

The cruelest month, early this year

Tuesday, March 01, 2022

Five-generation book

I come from a family of writers, did you know? My sister edits a prize-winning community newspaper, our paternal grandmother worked in publishing, and her father was a celebrated journalist for the New York Herald named Don Martin. Filling in the generational gap, my father edited a cache of letters he found between his mother, still a girl. and the grandfather he never met, in the months Martin spent covering WW1 in France (at the end of which he died of the Spanish flu). He shared them through the centenary of the Great War in a blog, and has now put them lovingly together into a beautiful book with the cover designed by his grandson! If you come over, ask me to show it to you: it's a thing of beauty. Or buy your own copy: everyone who's looked at it has found it compelling!

I come from a family of writers, did you know? My sister edits a prize-winning community newspaper, our paternal grandmother worked in publishing, and her father was a celebrated journalist for the New York Herald named Don Martin. Filling in the generational gap, my father edited a cache of letters he found between his mother, still a girl. and the grandfather he never met, in the months Martin spent covering WW1 in France (at the end of which he died of the Spanish flu). He shared them through the centenary of the Great War in a blog, and has now put them lovingly together into a beautiful book with the cover designed by his grandson! If you come over, ask me to show it to you: it's a thing of beauty. Or buy your own copy: everyone who's looked at it has found it compelling!