May 2007 surprise us all as a year of peace and reconciliation, joy and growth in understanding.

Mark's log of a year in Australia - and its continuing repercussions

in its having one man as its subject. An infinity of things befalls that one, some of which it is impossible to reduce to unity; and in like manner there are many actions of one man which cannot be made to form one action. One sees, therefore, the mistake of all the poets who have written a Heracleid, a Theseid, or similar poems; they suppose that, because Heracles was one man, the story of Heracles must be one story. (1451a17-22; trans., 234)]

in its having one man as its subject. An infinity of things befalls that one, some of which it is impossible to reduce to unity; and in like manner there are many actions of one man which cannot be made to form one action. One sees, therefore, the mistake of all the poets who have written a Heracleid, a Theseid, or similar poems; they suppose that, because Heracles was one man, the story of Heracles must be one story. (1451a17-22; trans., 234)] 14 degrees C, and Shepparton may have been even colder. Global warming swings both ways!

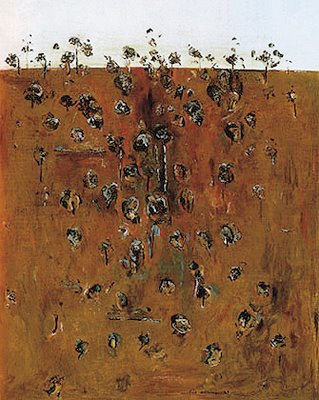

14 degrees C, and Shepparton may have been even colder. Global warming swings both ways! since he painted some wonderful work inspired by the red gums of Echuca in 1966, including this one (which also has a companion at the NGV, image unavailable).

since he painted some wonderful work inspired by the red gums of Echuca in 1966, including this one (which also has a companion at the NGV, image unavailable). Just had a lovely Christmas eve dinner at my sister's: fondue chinoise, a tradition we grew up with. The only change (besides eating it outdoors!) was that we had not just beef but some kangaroo meat, too, and with it some mint sauce. Very tasty. Indeed it was tasty enough to get my older nephew to try some, no small Christmas concession

Just had a lovely Christmas eve dinner at my sister's: fondue chinoise, a tradition we grew up with. The only change (besides eating it outdoors!) was that we had not just beef but some kangaroo meat, too, and with it some mint sauce. Very tasty. Indeed it was tasty enough to get my older nephew to try some, no small Christmas concession  from someone who ordinarily refuses to eat anything but cereal, peanut butter sandwiches, yogurt and dry noodles!

from someone who ordinarily refuses to eat anything but cereal, peanut butter sandwiches, yogurt and dry noodles! When I return I pledge to tell you a bit more about Melbourne (and about the book, yes, yes), of which I've suddenly realized I've given a most superficial picture. Just the languages on this cut-out sign (part of a special insert on preparing yourself for possible bush fires in today's paper) tell you more about Melbourne, or about more Melbournes, than anything you've heard from me: Italian, Greek, Arabic, Vietnamese, Chinese and Hebrew. If I forget, hold me to it.

When I return I pledge to tell you a bit more about Melbourne (and about the book, yes, yes), of which I've suddenly realized I've given a most superficial picture. Just the languages on this cut-out sign (part of a special insert on preparing yourself for possible bush fires in today's paper) tell you more about Melbourne, or about more Melbournes, than anything you've heard from me: Italian, Greek, Arabic, Vietnamese, Chinese and Hebrew. If I forget, hold me to it. (except for two scenes which prurient people found suggestive), so here's the cover of the children's book by Mem Fox on which it's based.

(except for two scenes which prurient people found suggestive), so here's the cover of the children's book by Mem Fox on which it's based. Rather it's a painting I saw it today in the National Gallery of Victoria. It's by John Longstaff and called "Gippsland, Sunday night, February 20th, 1898." The 1898 conflagration, known as the Red Tuesday bushfire, burned 260,000 hectares. 2000 houses destroyed, and a dozen people killed.

Rather it's a painting I saw it today in the National Gallery of Victoria. It's by John Longstaff and called "Gippsland, Sunday night, February 20th, 1898." The 1898 conflagration, known as the Red Tuesday bushfire, burned 260,000 hectares. 2000 houses destroyed, and a dozen people killed. Australian vowels, even the tamest and most British, sing more than our flat American ones, and achieve heights and depths we can’t muster. (I already tried a while back, not very successfully, to characterize what happens to my name here.) I’ve been trying for months to find a way of recording what happens to the words “thought, word and deed” I hear each week in the confession of sin at church. Something like thort, wööd and düeed, although there’s no ‘r’ in the first - it’s a deeper o, with the mouth making a tall narrow hollow - and the little fillip of ‘deeds’ is so quick as to be rising back before it really falls, more like the sound water makes when you pull your hand down quickly into it.) In the broader accents no diphthong goes unsung and you'll find a dipththong squatting in many a long vowel (as in ‘deed’). In some cases, finally, diphthongs are abbreviated to the component sounds Americans don’t pronounce, making it seem that high and low vowels have swapped places.

Australian vowels, even the tamest and most British, sing more than our flat American ones, and achieve heights and depths we can’t muster. (I already tried a while back, not very successfully, to characterize what happens to my name here.) I’ve been trying for months to find a way of recording what happens to the words “thought, word and deed” I hear each week in the confession of sin at church. Something like thort, wööd and düeed, although there’s no ‘r’ in the first - it’s a deeper o, with the mouth making a tall narrow hollow - and the little fillip of ‘deeds’ is so quick as to be rising back before it really falls, more like the sound water makes when you pull your hand down quickly into it.) In the broader accents no diphthong goes unsung and you'll find a dipththong squatting in many a long vowel (as in ‘deed’). In some cases, finally, diphthongs are abbreviated to the component sounds Americans don’t pronounce, making it seem that high and low vowels have swapped places.  Meanwhile the fires burn on; they claimed a first life the day before yesterday. This is another picture from The Age's website.

Meanwhile the fires burn on; they claimed a first life the day before yesterday. This is another picture from The Age's website.

Well, having just read her utterly delightful contribution to Australia's bicentennial in 1988, Joan Makes History, I understand now that Kate's a greater threat than Secret River and indeed a worthy opponent for Inga.

Well, having just read her utterly delightful contribution to Australia's bicentennial in 1988, Joan Makes History, I understand now that Kate's a greater threat than Secret River and indeed a worthy opponent for Inga.  By two-thirds of the way through the book, we start to notice more than parallels between the two stories - Australia's and the original Joan's. We come to understand that the original Joan has imagined these episodes not just out of some sense of fun or historical revisionism (though there's that too), but as part of owning and accepting her own life. Here are some reflections from the last pages of the book:

By two-thirds of the way through the book, we start to notice more than parallels between the two stories - Australia's and the original Joan's. We come to understand that the original Joan has imagined these episodes not just out of some sense of fun or historical revisionism (though there's that too), but as part of owning and accepting her own life. Here are some reflections from the last pages of the book: Joan wants to be bigger than Australia, wants a life like the politicians and artists of the old world who have lives bigger than out of the way Australia could ever make possible (she thinks). Eventually she discovers that history is made every day, and that it's made also (and indispensably) by women and women's work. That story could happen in any country. But that her life involves throwing herself into somewhat shallow passion in college, getting pregnant and reluctantly marrying the good-hearted man from the country who fathered the child and loves her although she never loved him, losing the child and abandoning her husband before eventually finding her way back to him and truer love, motherhood, etc. also tells (I think) a story about the difficulty of taking a life in Australia seriously. (Apologies to my Australian readers: I'm asking to be corrected here. Perhaps I read it this way just because I come from self-important America?)

Joan wants to be bigger than Australia, wants a life like the politicians and artists of the old world who have lives bigger than out of the way Australia could ever make possible (she thinks). Eventually she discovers that history is made every day, and that it's made also (and indispensably) by women and women's work. That story could happen in any country. But that her life involves throwing herself into somewhat shallow passion in college, getting pregnant and reluctantly marrying the good-hearted man from the country who fathered the child and loves her although she never loved him, losing the child and abandoning her husband before eventually finding her way back to him and truer love, motherhood, etc. also tells (I think) a story about the difficulty of taking a life in Australia seriously. (Apologies to my Australian readers: I'm asking to be corrected here. Perhaps I read it this way just because I come from self-important America?) lanyard-like needles on each branch. Glorious trees these are; I’m sure I’ll be posting more pictures of them (with, no without apologies to my nature-phobic friend).

lanyard-like needles on each branch. Glorious trees these are; I’m sure I’ll be posting more pictures of them (with, no without apologies to my nature-phobic friend). seems vindicated by the arrival this week, for the first time, of responses to the blog from people I do not know. Besides, Australia's all about nature.

seems vindicated by the arrival this week, for the first time, of responses to the blog from people I do not know. Besides, Australia's all about nature. months early. A 100 km line of fire is feared, with flames in places reaching up 70 meters. It's like a crouching cat, said one firefighter, and when it decides to pounce nobody can stop it. The Vicar of St. Peter's said this is more than human power can resist: the fire will burn until it reaches the sea. (This picture was posted by a reader of the The Age.) Meanwhile, we had our hottest December day in 53 years today, the mercury reaching 42.1 degrees this afternoon (108 F), though it cooled nearly 20 degrees over the next hour. "Four seasons in one day" indeed! What we need is rain and lots of it, and that's the one thing nobody's predicting.

months early. A 100 km line of fire is feared, with flames in places reaching up 70 meters. It's like a crouching cat, said one firefighter, and when it decides to pounce nobody can stop it. The Vicar of St. Peter's said this is more than human power can resist: the fire will burn until it reaches the sea. (This picture was posted by a reader of the The Age.) Meanwhile, we had our hottest December day in 53 years today, the mercury reaching 42.1 degrees this afternoon (108 F), though it cooled nearly 20 degrees over the next hour. "Four seasons in one day" indeed! What we need is rain and lots of it, and that's the one thing nobody's predicting.

Happily our bluestone house remains cool! But it does make me think back wistfully to Western Australia, and gliding through the warm blue waters of the Indian Ocean, seen above through a speed-splashed ferry window

Happily our bluestone house remains cool! But it does make me think back wistfully to Western Australia, and gliding through the warm blue waters of the Indian Ocean, seen above through a speed-splashed ferry window  (or is it the computer monitor?). I don't need to show you what Rottnest Island looks like, or where it lies - you've already checked that out on maps. google.com (as described a few posts ago). It's 19 miles west of Perth, far enough away to have a distinctive flora and fauna - most famous the quokka, a foot and a half-tall marsupial Dutch explorers mistook for rats (hence Rottnest). I surprised several as I wandered along the southeast tip of the island; they seemed always to be in pairs, and bounced into the brush like balls.

(or is it the computer monitor?). I don't need to show you what Rottnest Island looks like, or where it lies - you've already checked that out on maps. google.com (as described a few posts ago). It's 19 miles west of Perth, far enough away to have a distinctive flora and fauna - most famous the quokka, a foot and a half-tall marsupial Dutch explorers mistook for rats (hence Rottnest). I surprised several as I wandered along the southeast tip of the island; they seemed always to be in pairs, and bounced into the brush like balls. The summer holidays are just around the corner, but I managed to have beaches and bush practically all to myself! This beach on Bickley Bay, on which I saw no other soul, is five minutes' walk from the converted army barracks where I was staying (along with a class of high school students who - but only occasionally - put me in mind of Lord of the Flies).

The summer holidays are just around the corner, but I managed to have beaches and bush practically all to myself! This beach on Bickley Bay, on which I saw no other soul, is five minutes' walk from the converted army barracks where I was staying (along with a class of high school students who - but only occasionally - put me in mind of Lord of the Flies). But the real treat came on the north coast of the island (facing... India!), where, courtesy of the Leeuwin current, Australia's southernmost reefs invite even inexperienced snorkelers to make themselves at home. Many kinds of seaweed, corals and lots of friendly fish, just hanging out. I floated around along the tops of reefs, into sudden (shallow) canyons, occasionally guided by a friendly foot-long pale blue fish with yellow spots on his scales. It felt like a kind of bushwalking, with a local guide!

But the real treat came on the north coast of the island (facing... India!), where, courtesy of the Leeuwin current, Australia's southernmost reefs invite even inexperienced snorkelers to make themselves at home. Many kinds of seaweed, corals and lots of friendly fish, just hanging out. I floated around along the tops of reefs, into sudden (shallow) canyons, occasionally guided by a friendly foot-long pale blue fish with yellow spots on his scales. It felt like a kind of bushwalking, with a local guide! Now I'm glad to have braved the train out there mainly because it got me out west - and through Adelaide, a delightful little city I'll surely visit again. Rottnest I went to because my sister had been a few years ago - thanks for the tip! The big discovery was Perth and its port town, Fremantle, which I really liked. Perth has that San Diego vibe, and Fremantle a mix of old charm and new trendiness married by a winning sort of flakiness one might even call Californian (a term of praise!).

Now I'm glad to have braved the train out there mainly because it got me out west - and through Adelaide, a delightful little city I'll surely visit again. Rottnest I went to because my sister had been a few years ago - thanks for the tip! The big discovery was Perth and its port town, Fremantle, which I really liked. Perth has that San Diego vibe, and Fremantle a mix of old charm and new trendiness married by a winning sort of flakiness one might even call Californian (a term of praise!).  Of course I did have fantastic luck, catching Rottnest before the waves of holidayers, and catching a wonderful concert by the newly formed, Perth-based Arundo Reed Quintet in the courtyard of the Fremantle Arts Centre as exotic birds did their dusk swooping and cheering, where Byrd's "Browning" made me glow, Ton der Doest's "Circus Music" made me beam, and Contrapuctus IV from Bach's "Art of the Fugue" nearly made me weep for delight at - at everything: music, culture, nature, humanity and their unexpected counterpoint. (Both of these pictures are, of course, borrowed, but I'm sure I saw some of those friendly fish!)

Of course I did have fantastic luck, catching Rottnest before the waves of holidayers, and catching a wonderful concert by the newly formed, Perth-based Arundo Reed Quintet in the courtyard of the Fremantle Arts Centre as exotic birds did their dusk swooping and cheering, where Byrd's "Browning" made me glow, Ton der Doest's "Circus Music" made me beam, and Contrapuctus IV from Bach's "Art of the Fugue" nearly made me weep for delight at - at everything: music, culture, nature, humanity and their unexpected counterpoint. (Both of these pictures are, of course, borrowed, but I'm sure I saw some of those friendly fish!) The flight home was, surprisingly, less than four hours. We headed across the southwest tip of Western Australia and crossed the Great Australian Bight. (At left is where the bush which starts a few miles east of Perth meets the broad swath of the West Australian Wheat Belt.) Flying over water (and at least one stray iceberg!) made it seem like it indeed felt: Western Australia's on a different continent than Victoria - the Nullarbor is still a sea.

The flight home was, surprisingly, less than four hours. We headed across the southwest tip of Western Australia and crossed the Great Australian Bight. (At left is where the bush which starts a few miles east of Perth meets the broad swath of the West Australian Wheat Belt.) Flying over water (and at least one stray iceberg!) made it seem like it indeed felt: Western Australia's on a different continent than Victoria - the Nullarbor is still a sea.

Still in Perth, I'm starting to see how backpackers do it now - this internet cafe is wonderfully affordable. (Back in the day you disappeared when you traveled, now you're in regular contact with your friends back home, SMS'ing and e-mailing and blogging; is it just nostalgia that makes me think something is lost with all this, a sense of real stepping out and away from your life and culture, a real vulnerability and openness to the new?) And posting pics on the blog is easy as a charm. (Having said which, for some reason I can't see the pics on the blog after posting them; trust you can!)

Still in Perth, I'm starting to see how backpackers do it now - this internet cafe is wonderfully affordable. (Back in the day you disappeared when you traveled, now you're in regular contact with your friends back home, SMS'ing and e-mailing and blogging; is it just nostalgia that makes me think something is lost with all this, a sense of real stepping out and away from your life and culture, a real vulnerability and openness to the new?) And posting pics on the blog is easy as a charm. (Having said which, for some reason I can't see the pics on the blog after posting them; trust you can!)

I've missed the season of flowers, but you'd hardly know it, what with the many species of eucalyptus (this red one at the top seems to be getting decked out for Christmas, no?), banksia (which I'd always thought a South African plant, but apparently it's Australian - though it may be a survivor of the Gondwana flora which once spread over southern Africa, Antarctica, etc., too),

I've missed the season of flowers, but you'd hardly know it, what with the many species of eucalyptus (this red one at the top seems to be getting decked out for Christmas, no?), banksia (which I'd always thought a South African plant, but apparently it's Australian - though it may be a survivor of the Gondwana flora which once spread over southern Africa, Antarctica, etc., too),  kangaroo paws (which against the sun look like they were drawn by Keith Haring)...

kangaroo paws (which against the sun look like they were drawn by Keith Haring)... Arrived in Perth having crossed the mighty Nullarbor. Nor sure what hit me, to be honest – the Nullarbor, an ancient limestone seabed which goes for hundreds of miles without a stream or a tree, is so flat and featureless that the better part of yesterday we spent crossing it might have been just fifteen minutes, or a month. The sense of weirdness of the absence of physical landmarks was compounded by temporal uncertainty: South Australia is a cheeky 30 minutes behind Melbourne, Western Australia another 90 minutes beyond that (at least in summer time). Here are some pictures which will inevitably make the empty center of the trip seem even briefer. The top shows the sunset of our first night, gold to the west reflected in the eastward window's pinks and blues.

Arrived in Perth having crossed the mighty Nullarbor. Nor sure what hit me, to be honest – the Nullarbor, an ancient limestone seabed which goes for hundreds of miles without a stream or a tree, is so flat and featureless that the better part of yesterday we spent crossing it might have been just fifteen minutes, or a month. The sense of weirdness of the absence of physical landmarks was compounded by temporal uncertainty: South Australia is a cheeky 30 minutes behind Melbourne, Western Australia another 90 minutes beyond that (at least in summer time). Here are some pictures which will inevitably make the empty center of the trip seem even briefer. The top shows the sunset of our first night, gold to the west reflected in the eastward window's pinks and blues.  The Nullarbor.

The Nullarbor.

(Top:) Trees start – but it’s not as many as it looks like, this is much zoomed. (Above:) Outback at last!

(Top:) Trees start – but it’s not as many as it looks like, this is much zoomed. (Above:) Outback at last!

I'll try to find an internet café when I arrive in Perth on Tuesday. Maybe I'll even be able to post some pictures, though the famously flat and treeless Nullarbor may be hard to surprise with a candid snap, and I may have been reduced to a wide-eyed and inarticulate wow-wow-wowing. Have a good week!

I'll try to find an internet café when I arrive in Perth on Tuesday. Maybe I'll even be able to post some pictures, though the famously flat and treeless Nullarbor may be hard to surprise with a candid snap, and I may have been reduced to a wide-eyed and inarticulate wow-wow-wowing. Have a good week!