The semester is wending its way to a close - three more weeks, can it be? - including our seminar devoted to Mary-Jane Rubenstein's Pantheologies: Gods, Worlds, Monsters. Next week the author joins us (virtually) so we spent today's class recapping and refreshing - and rediscovering what a brilliantly constructed argument it is, too.

Our mechanism was a quiz, generated by the class itself, which identified key arguments, figures and tropes. Students had each been charged with sending me 2-3 questions and I selected a baker's dozen (arranging and, I'll admit, adding a few too). At the start of class, students were given the questions (13 and a bonus) and tasked with writing brief responses to eight of their choosing. We'd spend half an hour like this, and another half hour going through the questions. As if! Working through the questions took almost our whole 2.5 hour class! Students had also been asked to generate a 2-3 page synopsis of the book, so the discussion was synthetic and illuminating: we were considering this rich complicated book as a whole, from a variety of angles, with plenty of enjoyable deep dives.

One of the most enjoyable discussions came near the end:

11. What is a peccary? (Trick question!)

It was one of my plants, and I placed it between student-generated questions on how Rubenstein's pluralistic pantheism deals with the problem of evil and another on the affective, ethical and symbol benefit she finds in thinking our buzzing symbiotic world divine. So... what's a peccary? And what's the trick?

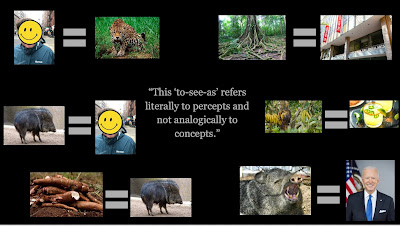

This is a peccary at the San Diego Zoo but the question isn't (just) about this animal ("don't call it a pig"!). It led us to Rubenstein's discussion of the "Amerindian perspectivalism," the name given for the distinctive worldview of Tupi other Amazonian peoples according to which all species regard themselves as human. Accordingly, they identify other things related to them by the same names we use for things related to us in the same way way: a predator they might call jaguar, a prey animal might be peccary, an enjoyable intoxicant beer. This means that where a human like you or me will see a peccary as a peccary and a jaguar as a jaguar, the peccary will see itself as human and see us as jaguars, while jaguars will see themselves as human and us as peccaries. Or something like that... since all these words melt through our fingers as we try to hold them. How do we know we're not peccaries?

I'm not as entranced by the delirious weirdness of "Amerindian perspectivism" as some are, so I didn't really understand what it was doing in her book ... until today. Playing out the slippery undecidability of sorting humans from peccaries with the class, I got its equivocal charm and how it serves her "hypothetical pluralistic pantheism." Humans and/or peccaries and/or all the other symbiotic agents with whom we make the world are right to feel at home in the world, and wrong only when they forget that all the others have valid claims to knowing what's going on, too, which are and are not just like ours. (The Tupi don't forget; you stay away from what seem to you jaguars, and you hunt what seem to you peccaries, all with the respect that is due one's relations. That we all collectively maintain the world is understood.) For getting beyond anthropocentrism, it's too little and too much! But, I saw, it opens up some of the affects of humility and awe and flow which Rubenstein thinks make pluralist pantheism ethically and spiritually viable and valuable.

The 13th century picture above isn't of peccaries; the Bodleian Library, in one of whose books it appears, says it's hedgehogs among grapes. But it's the picture Pantheologies has on its cover and I'm going to say that, just as those vines are also kin to the sky and the earth, those animals may know themselves to be more than hedgehogs. Rubenstein's pantheologies are teeming with possibilities, most beyond our grasp and yet not beyond our awed awareness and participation.

|

| A student's key to peccary perspectivism |