Tuesday, January 31, 2023

Stick 'em up

Monday, January 30, 2023

Interview with the vampire

Robin Wall Kimmerer got to headline the New York Times Magazine this weekend. Unfortunately it was a conversation with someone who channeled the dumbest forms of skepticism, but I suppose it does surface what Kimmerer's approach is up against. The interviewer David Marchese seems to have thought it is job to offer her offramps back to mainstream Western views of a hostile natural world.

Robin Wall Kimmerer got to headline the New York Times Magazine this weekend. Unfortunately it was a conversation with someone who channeled the dumbest forms of skepticism, but I suppose it does surface what Kimmerer's approach is up against. The interviewer David Marchese seems to have thought it is job to offer her offramps back to mainstream Western views of a hostile natural world.

There’s a certain kind of writing about ecology and balance that can make the natural world seem like this placid place of beauty and harmony, he begins disingenuously. But the natural world is also full of suffering and death.1 Do you think your work, which is so much about the beauty and harmony side of things, romanticizes nature?

[Even sleazier, he adds a "footnote" to his question, quoting "visionary" Werner Herzog, which the reader will assume Kimmerer didn't see, but accept as "apt."]

[Even sleazier, he adds a "footnote" to his question, quoting "visionary" Werner Herzog, which the reader will assume Kimmerer didn't see, but accept as "apt."]

Unquestionably the contemporary economic systems have brought great benefit in terms of human longevity, health care, education and liberation to chart one’s own path as a sovereign being. But the costs that we pay for that? It goes back to human exceptionalism, because these benefits are not distributed among all species.

She punts gamely in this way on all his stupid questions, and I suppose some people might be inspired by her answers to learn more about her work. Surely 1.4 million readers of Braiding Sweetgrass can't be wrong! But the coherence of her views, their roots in both indigenous and botanical wisdom, and her celebration of the love-ful "democracy of species," never really have a chance to show themselves. A shame.

Saturday, January 28, 2023

Sylvan ruminations

Friday, January 27, 2023

Thursday, January 26, 2023

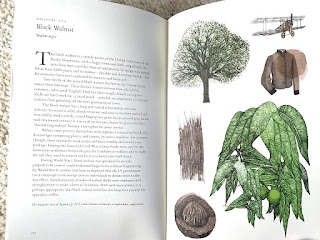

Gifts of trees

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

Bühnenweihspiel

Ever After

In a lecture hall again - first time since Spring 2020! To celebrate I placed our class in a lineage of classes and events from 1920, 1951, 1963, 1968, 1983, 2012.

In a lecture hall again - first time since Spring 2020! To celebrate I placed our class in a lineage of classes and events from 1920, 1951, 1963, 1968, 1983, 2012.

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

Monday, January 23, 2023

Heavenly banquet

Saturday, January 21, 2023

Inhabiting ideals

Friday, January 20, 2023

Double takes

Thursday, January 19, 2023

Wednesday, January 18, 2023

Visions

with a cuneiform text on her lap (c. 2112-2004 BCE) above, or these scenes of weavers (c. 3300-3000 BCE), an all-female sacrificial scene (c. 2334-2154 BCE) or an all-female banquet (c. 2500 BCE). Even some of the images of goddesses - like this one from c. 2400 BCE - seem like real women!

with a cuneiform text on her lap (c. 2112-2004 BCE) above, or these scenes of weavers (c. 3300-3000 BCE), an all-female sacrificial scene (c. 2334-2154 BCE) or an all-female banquet (c. 2500 BCE). Even some of the images of goddesses - like this one from c. 2400 BCE - seem like real women!

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)